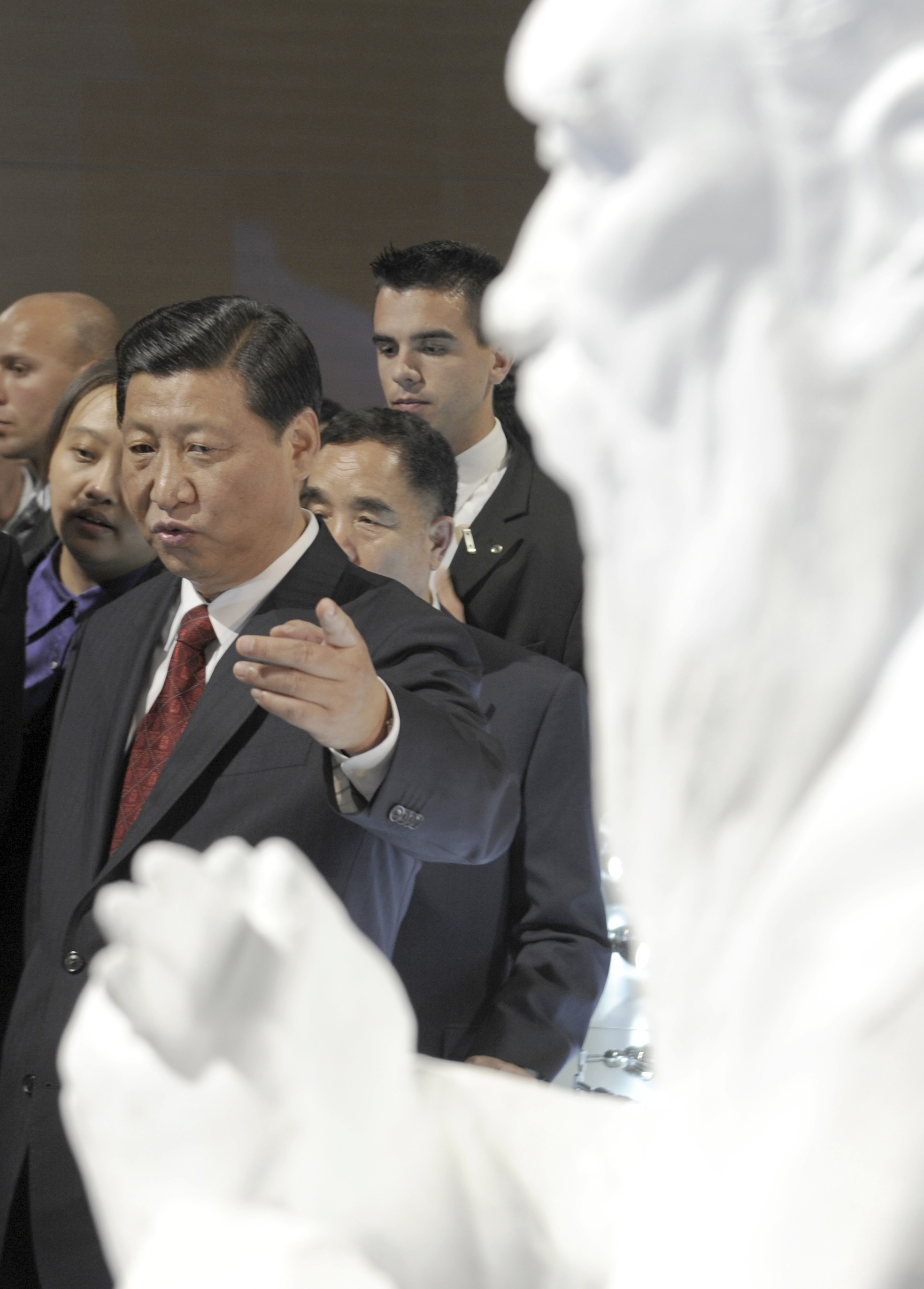

Ever since China’s President, Xi Jinping, first began to claim the reins of power in Beijing nearly two years ago, China watchers have speculated on where he would take the budding superpower. Initially, it was widely held that Xi was more of a folksy, “man of the people” than his aloof and expressionless predecessor, Hu Jintao, and that he would be a bolder, more liberal reformer.

So far, though, those assumptions have proved off the mark. He has cracked down severely on social media and dissent, with the apparent aim of strengthening the Communist Party’s grip on society. On the economic front, he announced a sweeping program of liberalization, but hasn’t yet implemented it, and the hand of the state rests as heavily on business as before. That has left China analysts grasping at oracle bones to decipher Xi’s vision for China’s political future.

However, a picture of Xi’s agenda is beginning to emerge through the usual haze of secrecy surrounding communist leaders, and it features a man who lived 2,500 years ago: Confucius, the most influential of history’s Chinese philosophers. Simply, Xi is turning to China’s glorious past to provide an ideological foundation to his 21st century rule.

Though Xi has also invoked other figures from Chinese history — from philosophers of competing schools to more modern personalities like Mao Zedong — the President seems to take special interest in Confucianism. “Do not impose on others what you yourself do not desire,” he said in a September speech, quoting one of Confucius’s most-famous sayings. Earlier in the year, he extolled the wonders of benevolent rule in an address to party cadres with another, well-known passage from the Analects, the most authoritative text on Confucius’s teachings: “The rule of virtue can be compared to the polestar which commands the homage of the multitude of stars without leaving its place.” Last year, Xi, like so many Emperors of old, visited Qufu, Confucius’ hometown. During his tour, he pledged to read Confucian texts and praised the continuing value of Chinese traditional culture.

There is, of course, great irony here. For the first 30 years of communist rule in China, the party of Mao Zedong had tried to uproot Confucian influence from society, seeing the enduring legacy of Confucius as an impediment to socialism and modernization. During the tumultuous Cultural Revolution, launched by Mao in the mid-1960s, Red Guards rampaged through Qufu, smashing relics and defacing the old Confucian temple. In communist propaganda, Confucius was vilified as a feudal leftover responsible for the oppression of the common man.

Since the early days of reform in the 1980s, however, the party’s leaders have been (slowly) resurrecting Confucius and his ideas. Beijing’s successful program to introduce capitalism — or what it prefers to call “socialism with Chinese characteristics” — made the government’s Marxist rhetoric sound especially hollow, leaving the communists to return to Confucius instead.

The sage’s ideas about harmony and deference to authority, they believe, offer an authentic Chinese doctrine that can support the political status quo (and deflect Western ideals of liberal democracy). Much like the imperial emperors did for centuries on end, China’s new communist leaders are attempting to cloak themselves in Confucian principles to lend credibility to their tightfisted tendencies.

Xi seems to be taking this effort to a whole new level. He appears to be employing Confucius as part of a broader program to remake the Communist Party and realign the power structure within it.

For instance, Xi apparently believes a dose of Confucian morality will aid stamping out official graft. Over the past year, Xi has launched an aggressive campaign against government corruption, likely engineered to both eliminate political enemies and clean up an out-of-control bureaucracy that had lost the trust of the populace. A high-level Communist Party conference in October pledged to strengthen the independence of the judicial system to improve rule of law.

Confucius is part of Xi’s reform team. For 2,000 years, Confucius’s doctrine laid down the code of ethics for proper behavior in China — the way of the gentleman — and now Xi seems to be trying to recreate those Confucian standards through persistent exhortation.

Xi also apparently believes that Confucius can bolster his own standing in the country. Confucius’ ideal government was topped by a “sage-king” — a person who was so learned, benevolent and upright that his virtuous rule would bring peace and order to society and uplift the Chinese masses both spiritually and materially. Confucius made little progress in achieving this vision during his own lifetime. But Xi seems to be resurrecting the idea. Since becoming President, he has been whittling away at the government by committee that had prevailed for two decades, in the process centralizing more power in his hands than any communist leader since Mao. By combining one-man rule with the morality of Chinese antiquity, he appears to be painting himself up as some newfangled communist/Confucian sage-king — an all-commanding figure who will usher in a new epoch of prestige and prosperity.

But resurrecting Confucius remains a big risk. Confucius held his sage-king to the strictest principles of virtue and righteousness. The true sage-king was so benevolent that laws and jails would become unnecessary — the people would willingly follow his lead. By quoting and honoring Confucius, Xi is also potentially holding himself to the sage’s unobtainable moral precepts. Simply, the higher the Confucian pedestal on which Xi places himself, the farther he has to fall.

Nor does Xi seem willing to implement other aspects of Confucian government. Kings were not supposed to be autocrats in his teachings. Ministers and other officials were bound by duty to protest policies they considered misguided to keep the Emperor on the proper path. Government was not to tread heavily into the lives of ordinary people. Kings may have had ultimate authority, but not unlimited power. Xi, however, doesn’t appear interested in easing the repressive machinery of the state, nor accepting any challenges to or limitations on his authority.

It appears, then, that Xi really wants to create not sagely Confucian rule but “authoritarianism with Chinese characteristics.” Confucius, if he were alive today, would not approve.

— With reporting by Gu Yongqiang / Beijing

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com