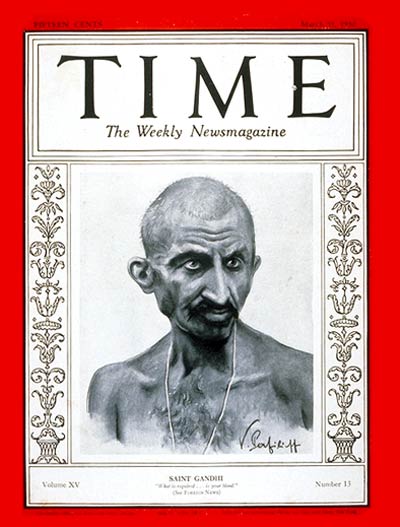

Before he was the pioneering civil rights activist called by the honorific “Mahatma” (“great soul,” in Sanskrit), Mohandas Gandhi was a young attorney just trying to take his seat on a train.

Not long after moving to South Africa in 1893 to help an Indian merchant with a legal problem, he was kicked out of the first-class section of a train — despite having bought a ticket for it — after being told, “This is for whites only,” according to Ramachandra Guha, the author of Gandhi Before India. “He had just come from England, where — at least in London in the 1890s — professionals who were colored did not face discrimination,” Guha said in an interview with NPR. The experience was both humiliating and eye-opening, and set the stage for the civil disobedience that would become Gandhi’s legacy.

He paid a price — including four periods in jail during his 21 years in South Africa — for demonstrating against discrimination, but continued with protests, such as leading Indian expats in opposing a racist law requiring all Indians to register with the “Asiatic Department” and to carry their registration cards at all times or risk deportation. His final stint in a South African prison began with his arrest on this day 101 years ago — Nov. 6, 1913 — for leading a march of more than 2,000 people to protest a tax on Indian immigrants.

While he left South Africa for good the following year, his arrest record was far from complete.

Going to jail was, in fact, one of the sharpest tools in Gandhi’s nonviolent tool belt, along with fasting (or a combination of the two). According to TIME’s 1948 report on his assassination, British authorities often freed him from jail when he began to fast, “lest a massive anger at his death in their hands engulf India.” Gandhi himself once said, according to the story, “I always get my best bargains behind prison bars.”

The lessons he learned about the effectiveness of peaceful protest in South Africa formed the basis for his efforts to end British oppression in India. In the book Satyagraha in South Africa, Gandhi relates a conversation with a tailor in 1915, just after returning to India.

He gave me some account of the hardships inflicted on the people in Viramgam, and said:

“Please do something to end this trouble…”

“Are you ready to go to jail?” I asked.

“We are ready to march to the gallows,” was the quick reply.

“Jail will do for me,” I said. “But see that you do not leave me in the lurch.”

Read TIME’s original coverage of Gandhi’s assassination, here in the archives: Saints & Heroes: Of Truth and Shame

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com