It was pretty impossible not to notice that something bad had happened: in the days leading up to Oct. 29, 1929, the stock market was already reeling from a series of smaller sell-offs leading up to “Black Tuesday,” the day commonly used to mark the onset of the Great Depression.

But with only a few days of hindsight to put that event into perspective, it was pretty easy not to see how bad things were.

TIME was one of the outlets that made that very miscalculation. Reporting on the stock market in a Nov. 4, 1929, article, TIME recounted that the liquidation of stocks that day “might technically be termed orderly but was certainly extremely depressing.” (That take now seems ironically apt.) But the sell-off was balanced out by plenty of “don’t panic” speechifying — President Hoover said that Industry in the nation was “sound.” By the end of the day, TIME reported, “it seemed again that the worst was past.”

A move by the country’s biggest bankers to shore up the market by purchasing stocks had, it appeared, worked. Along with the lack of hindsight, that effort was partly to blame for the miscalculation. For example, a few days before Oct. 29, the broker Richard F. Whitney had personally stopped a panic by buying shares of U.S. Steel at 15 points above its market value; at a time when the whole banking industry seemed ready to take such extraordinary measures to save the economy, and when the market had done so well for so many years, optimism would have been easy. (Whitney later became president of the New York Stock Exchange. After that, in 1938, he went to jail for grand larceny.)

“Hysteria, it was hoped, had met its master in the Banking Power of the U.S.,” TIME wrote. That quote would later make it into TIME’s 75th-anniversary run-down of the most off-the-mark statements in the magazine’s history, alongside predictions that war would end in the 20th century and the sincere belief that the media would stay out of Bill Clinton’s personal life.

Even a week after the crash, when the economy was the Nov. 11, 1929, cover story, the gist of the story was that the valiant bankers who had banded together to keep things orderly had prevented the worst of possible outcomes. (This version of history, while incorrect in its optimism, may well be true nonetheless; it’s always possible that the Great Depression could have been even worse than it was. As long as The Hunger Games is still fiction, that will always be true.) As TIME reported:

Monday, Nov. 4, when the Exchange re-opened there were more sellers than buyers but none were frenetic. Toward noon prices climbed, then dropped again. In general stocks closed lower than Thursday. U. S. Steel closed at 180, Radio at 43¼, General Motors at 45¼. The market except at the very opening was dull as though it were tired. But it seemed to rest securely. Stock Exchange Governors ordered the Exchange closed after 1 o’clock Wednesday, Thursday, Friday; all day Saturday. Tuesday was a legal holiday (election day). Thus was further rest insured.

Friday there were no quotations nor Saturday for the Exchange was closed. Clerks who had passed many a sleepless night, slept, then returned to clean up the greatest amount of work which brokerage houses have ever had in so short a time. In the hurly-burly many an error had been made. The clerks had to discover them, rectify them. But in the Stock Exchange Friday and Saturday there was quiet.

Thus did Confidence win its subtle race against Panic.

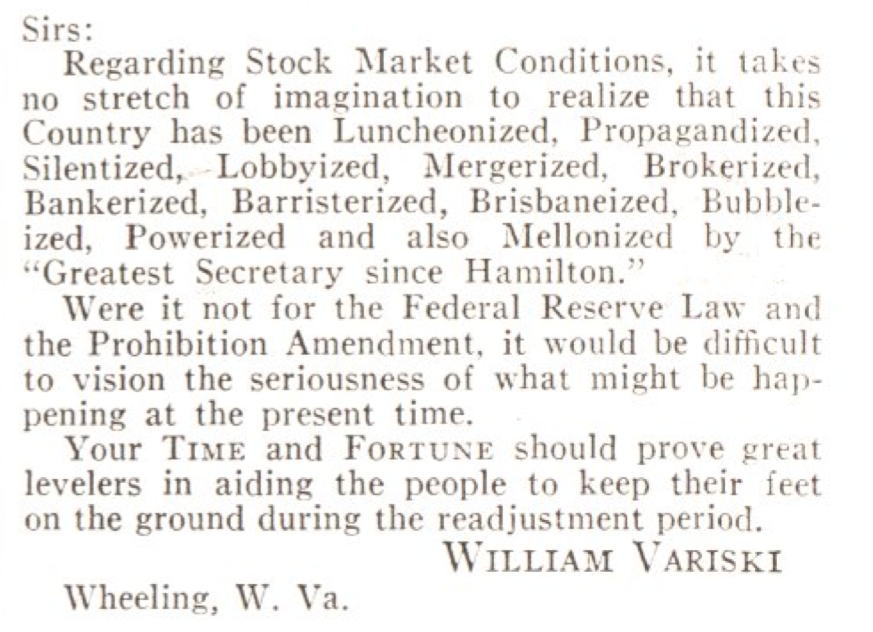

But not everyone was having trouble seeing what was about to happen. The following letter ran in the Dec. 2, 1929, issue:

Read Niall Ferguson’s comparison between 1929 and 2008 here in TIME’s archives: The End of Prosperity?

Read more: A Brief History of the Crash of 1929

Photos: The Crash of ’29

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com