There’s something a little ironic about Men, Women & Children director Jason Reitman interrupting an interview about how technology is harming kids today to answer a FaceTime call from his young daughter. But as the filmmaker behind Juno and Up in the Air explained last month at the Toronto International Film Festival, parents “got saddled with a very tricky job and no way to do it right” when it comes to raising kids in an era where hardcore pornography is just a click away.

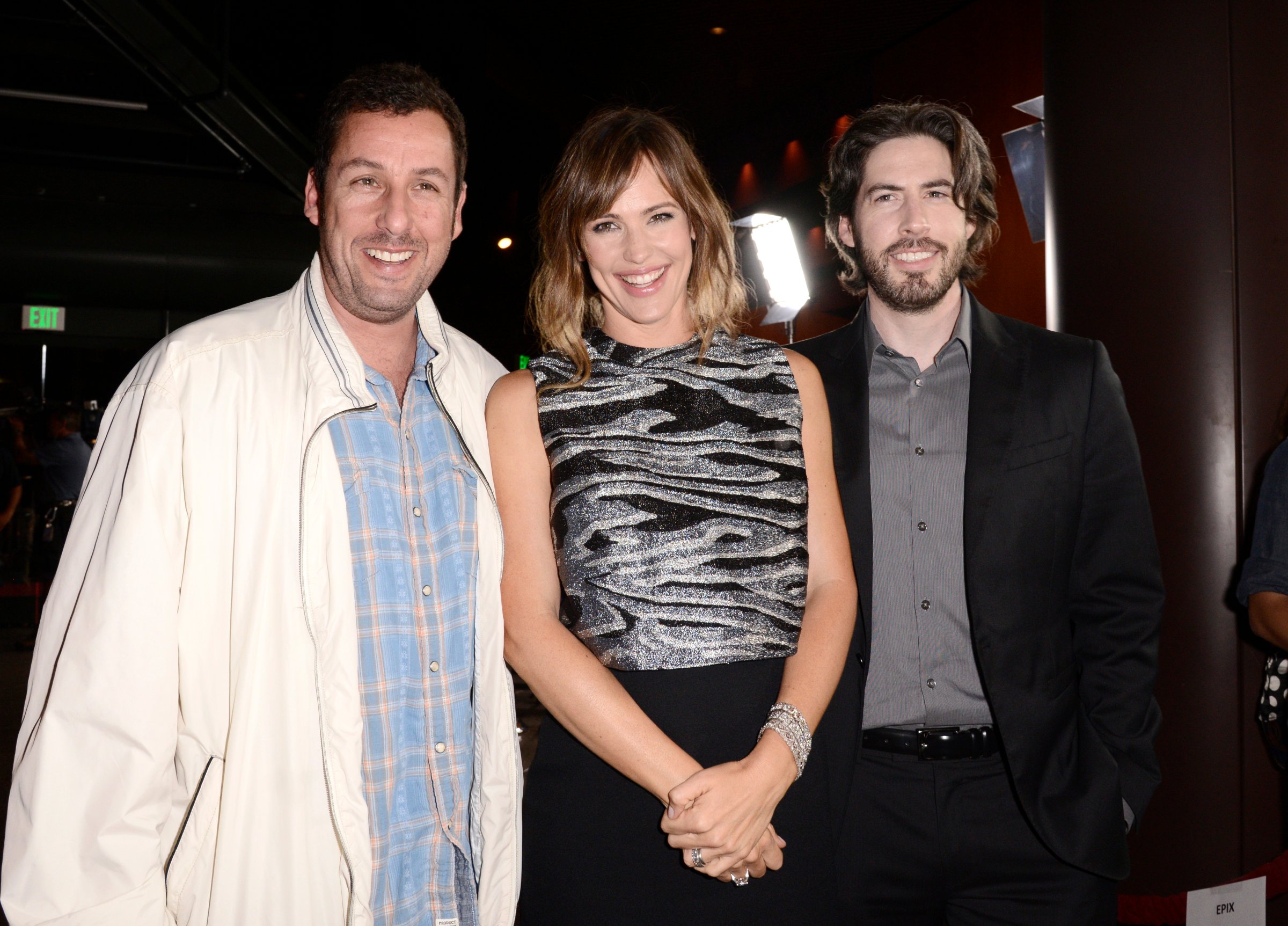

Men, Women & Children, now in theaters, follows an ensemble cast of characters (played by Jennifer Garner, Adam Sandler, Ansel Elgort and others) as they develop porn addictions, sign up for cheating websites and generally see their sex lives and relationships suffer from too much Internet and social media. TIME spoke to the director in September about the movie and what it has to say about finding intimacy in 2014.

TIME: This movie deals a lot with what I’m sure keeps many parents up at night — sexting, secret websites, teenagers interacting with strangers online. So what are you most horrified by?

Jason Reitman: There’s general horror, and there’s specific horror. The general horror is that we clearly are in search of intimacy, and the movie explores that. The movie opens with us launching this golden record up into space as this desperate attempt to make a connection with something we don’t even know exists. And then it shows people on their devices trying to make human connections left and right. I strangely think there is connective tissue between us launching Voyager and us using Tinder. We just desperately want to connect. And we’re doing in it perhaps in the wrong ways.

And then there are the specifics. I have a daughter who’s going to turn 8 next month. She is one innocuous search query away from seeing stuff and learning stuff she simply doesn’t need to know yet. I don’t think there’s time to list the amount of fears that come from the Internet and how it affects our intimacy, our sexuality and our communication.

This movie is based on the book of the same name by Chad Kultgen. How do you adapt a story about technology with technology changing so quickly?

All the plot lines originate in the book and focus on how the Internet has changed our sexuality. The only thing that’s changed is that over five years, you go from MySpace to Facebook. Twitter exists, Instagram exists, Snapchat exists. The sites change, but the concept stays the same. Thinspiration and pro-ana, I wasn’t aware of until I read the book, and [it] completely freaked me out. And there was this concept of — and I don’t think there’s a word for it yet — this kind of young pornography addiction that leads to impotence. That’s scary, the idea that teenage boys would not be able to have traditional intercourse because they’ve brainwashed themselves.

There doesn’t seem to be an example in this movie of technology helping anybody have a better relationship with their body or sexuality. Do you think that doesn’t exist?

The shining example in the film is the couple that’s basically not online, and everyone else is struggling. The most positive examples of the Internet helping, for me, are not sexual. I look at the Arab Spring. I look at Ferguson. I look at the ways in which communication and connectivity are broadening our horizons and allowing us to see racism in a new light and police brutality in a new light. That’s a definite positive and something interesting, something you can kind of quantify. Within the realm of sexuality, I think the Internet can be enlightening as far as reducing homophobia hopefully in the future. And certainly you can point to Match.com — I guess it’s going to bring couples together that would otherwise not meet. It certainly raises the possibility of second and third marriages, relationships later in life where it seems harder and harder to meet available people.

I feel like there are a lot of sex-positive communities and resources on YouTube and Tumblr now.

Yesterday Ansel Elgort brought up the concept that there should be classes in school that teach this kind of stuff. That teach the dangers of the Internet, and the positives, and play into human sexuality. There’s a course that they give athletes when you become an NFL player or an NBA player. There’s a three-day weekend where they take you through the dangers of life, and one would say you could apply this course now to all teenagers and say, “This is what’s coming down the road.”

It probably has to start earlier than teen years now?

That’s the question, right? If you can read and write by 7, 8 years old, you can type then, and once you can type something as a search query, then it’s game over. But 8 years old is probably too early to learn. It’s somewhere between 8 and 12, there’s a moment where you have to catch them.

I just read an article the other day about a father who discovered his 9-year-old had already looked at porn. He was willing to talk to his kid about it, but he also thought that conversation was a few years down the road.

It’s funny, if you think about the greatest scientists of our time, what is the study? The study is where we come from. They’re studying the Big Bang, they’re studying, “What is the conception of the universe and of human life?” And as children we are just intrigued. My daughter’s already come to me and asked — and she had a great way of phrasing it — “I know I’m half mommy and I’m half you, but how do you get the half you into mommy?” And there’s something about that first search for pornography that while, yes, is perhaps titillating, perhaps is way more about, “Where do we come from?” You want to see it, and you want to know it, and those questions start earlier than 12 years old. I mean, I’m trying to think when I looked at my first Penthouse. It was before I was 12. Maybe it was closer to 10. The question is, how do you vary the lesson plan?

Is the issue of 10-year-olds looking at porn more about updating sex-ed programs or about teaching kids how to responsibly use the Internet at an early age?

Listen, I’m not a sex researcher or a psychologist, I’m just a guy who makes movies, so I’m not sure really what my answers are worth in this subject, to be perfectly honest. My gut is that it comes down to other stuff at the end of the day. If you can teach your kid the old-fashioned — self-confidence, the ability to be open and honest and ask questions to the people they trust — hopefully that counteracts the more dangerous behavior, which is going online to look for the wrong community to answer your questions. The wrong community could be a thinspo board, the wrong community could be PornHub, the wrong community could be just some forum of adults who down the rabbit hole in the way that a 10-year-old shouldn’t be. So yeah, I think you have to prepare your children logistically for what they’re going up against. You’re not going to give the kids the keys to the car if they don’t know how to drive. And at the same time — I’m sorry, this is my daughter, one second. [Reitman briefly FaceTimes with his daughter.] It’s very fitting of this conversation!

So is the burden entirely on parents at this point?

Everyone has different opinions, but yes, I am a believer that parents should parent their children and give them the key stuff, the key life shit that makes us prepared for the interpersonal stuff as well as the inter-technology stuff.

If you’re raised to love yourself more and communicate with your family more, then you’re going to have a better shot when people you never met online try to infiltrate your brain. You don’t search for the wrong things to feel loved. I’m constantly thinking about the ways I look for love and the ways other people look for love. The Internet opens up so many false opportunities to feel loved, whether you’re paying to iChat with a porn star or whether you’re going on a community and sharing your fears, and people are validating your fears in the wrong way. For me, it gets less about the physicality of sex and more about the deep desire for intimacy. Intimacy is such a potent thing that we will follow the fragrance very fall down the road, the wrong road.

There are no rules [on the Internet]. When we were kids, your parents could say something as simple as “Don’t watch an R-rated film.” There isn’t any “don’t watch an R-rated film, don’t go into an adult shop.” Now it’s, “Don’t go into the grocery store because aisle three may be cereal, but aisle seven is hardcore pornography!” I’m not worried about PornHub, I’m worried about Google, I’m worried about YouTube. That makes me sound like Patricia [Jennifer Garner’s character, an extremely overprotective mom] in the movie, but it’s true. The avenue to fruitful information is at an intersection with the avenue to everything my daughter should not be looking at at 8 or 18. We got saddled with a very tricky job and no way to do it right. We’re making the best effort. People are seemingly resilient. We’re very curious and somehow haven’t blown ourselves up. We seem so capable of annihilating ourselves, and we’re still kind of on the right track. We’re going to figure it out.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Nolan Feeney / Toronto at nolan.feeney@time.com