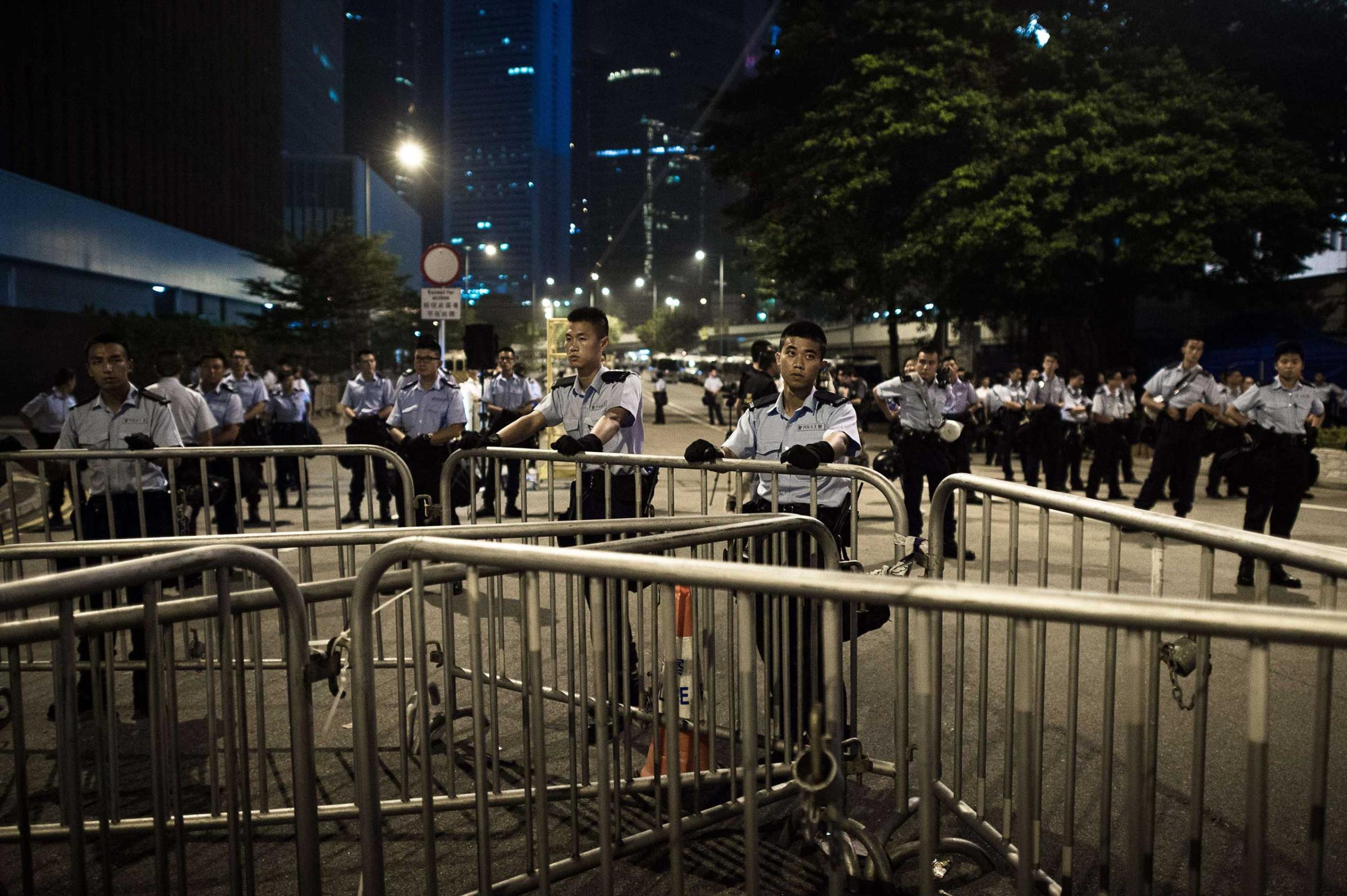

Dawn in Hong Kong would break in little more than an hour, and the young men at the barricades early on Oct. 6 were nervous. A 25-year-old tech executive’s eyes filled with tears, and he clenched his jaw. Rumors, they said, had mysterious men in black shirts amassing in a restaurant in the Wanchai district, just down the deserted avenue from the roadblocks that members of Hong Kong’s protest movement had set up more than a week before.

The stretch on Queensway, in the shadow of government offices, the High Court, and a shopping mall, was empty save the few jittery barricade defenders and a fellow protester who snoozed on a wooden plank. Two of the men had wrapped their hands in towels they hoped might protect their knuckles from whatever violence might come their way.

“We don’t know what will happen,” said the 25-year-old, peering east into the dark toward Wanchai. “But we are scared.”

The men in black shirts did not materialize. Nor did the police. Despite a vow from Hong Kong’s top leader, Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying, to clear major streets for the beginning of the workweek, the Hong Kong protest movement still occupies major commercial areas in the Asian financial capital. By daybreak on Monday, the number of journalists and protest tourists prowling the main demonstration site in Admiralty almost outnumbered the remaining protesters. Still, the barricades, set up to defend a movement demanding democratic commitments from the Chinese central government, held.

“I choose to stand up,” says Jennifer Wong, a 17-year-old high school student from the New Territories, near the border with mainland China. “Maybe [the movement] will not work in the end, but we will regret it if we don’t try.”

Protest leaders, from the three main groups that had banded together to establish this democratic crusade 10 days ago, strategized throughout Sunday as Leung’s ultimatum to disperse loomed. Powwows took place in the quiet halls of the Legislative Council building, where two of the protest blocs had set up makeshift command headquarters. But it was not clear who had the authority to negotiate on behalf of the protesters (or wanted to exercise that power), nor was it apparent who formally represented the government’s side. “The beauty of the movement is that there is no leader,” said one adviser to the Occupy Central group, which kick-started the peaceful siege that has drawn tens of thousands of Hong Kong residents, many of them young and middle class. “But that’s also its flaw.”

Outside the Legco building, dozens of protesters tended to their encampments, accepting donations of drinking water or adjusting pieces of cardboard that served as both bedroom and living room. Some had been there since the beginning and had clear demands: the resignation of Chief Executive Leung, who is considered the central government’s proxy in Hong Kong, and a rollback of Beijing’s plan to prevent the territory’s voters from directly electing their leader in 2017. Others had joined the protest movement later, shocked into action by the aggressive tactics that had been used to try to break up the rallies, including police tear gas and thuggery from elements linked to Hong Kong’s triad mafia.

It’s clear that the protesters are joined in their anger toward Beijing, which they feel is degrading the liberties that make Hong Kong a unique city in China, such as an independent judiciary and media. (When the former British colony was returned to China in 1997, the outpost was promised a high degree of autonomy for 50 years under a formulation called “one country, two systems.”) For the demonstrators, Leung is also a vilified character, maligned as much for his Beijing yes-man reputation as for the decision to unleash tear gas and pepper spray on the protesters on Sept. 28. But unity of message doesn’t necessarily mean that the protesters are falling in line behind a certain individual who can carry the movement forward.

“We all want the same thing,” says Daisy Lee, a 33-year-old clerk. “But we’re not here because we support one person or one group.” Lee worries that the diffuse nature of the rallies could undercut their ultimate effectiveness. “I’ve spent so many hours here,” she says. “But none of the so-called trio of groups has come to talk to us. Are they communicating with each other? We don’t know. We need strong leadership.”

Already, certain demands from protest leaders have gone unheeded by the rank and file, like a call from student activists to consolidate and abandon a satellite protest site across Victoria Harbour. On Sunday afternoon, a message went out from the Occupy group announcing that protesters had pulled back from a picket at the entrance to the chief executive’s office. But as night fell, students and other youth, surrounded by the inevitable journalist hordes, maintained their vigil at that precise point.

On Monday morning, the diehards that remained stood by as civil servants trooped in to work. Crisis had been averted and ultimatums or conditions from both sides were politely ignored. Throughout Monday, more talks were to take place between the myriad players in this unlikely movement. From a scorecard perspective, the protesters had prevailed the night before by peacefully defying the government’s order to cease and desist. But it’s still hard to see what significant political concessions they can wrest from Beijing, which has been churning out articles and cartoons in the state-run media both deriding and assailing their civil disobedience. Conciliatory moves by Chinese President Xi Jinping could make his administration look weak, and he has not given the impression of a leader enamored by the art of compromise.

As the workweek began in Hong Kong and traffic snarled because of the protest roadblocks, patience from a sector of ordinary citizens may wear thin. Already, some Hong Kong residents were quietly criticizing the continuing shutdown of major business and tourist areas. “Of course I support more democracy for Hong Kong and am not opposed to [the protesters’] ideals,” said a woman surnamed Liu, who came with her 11-year-old son to look at the occupied site in Mongkok district. “But we need to eat, to do business. How can we do that when they take over the streets?”

Whatever happens, Hong Kong’s political consciousness has been awakened. Emily Lau, a veteran local legislator, jokes that she’s been labeled “a head-banger” for her decades of pro-democracy work. “It’s very invigorating to have such a spontaneous, peaceful movement full of young people,” she says. “Once people have been shown their power they will know how to use it again and again.”

Lau could well be talking about Tanson Tsui, a high school student with a backpack full of English homework who was camped out at the entrance to the chief executive’s office on Sunday night. Tsui was born in 1997, the year the British handed Hong Kong back to China. “I came here because of myself,” he said. “I am not following anyone, I have no leader. I will fight to the end because I am Hong Kongese and I have to protect my home.”

— With reporting by Zoher Abdoolcarim / Hong Kong

— Video by Helen Regan / Hong Kong

Photographs of Hong Kong’s Umbrella Revolution

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com