As the owner of a hotel in 1960s Libya, Mohamed Nga lived in the rarefied circles of Tripoli’s cosmopolitan society. His son, photographer Jehad Nga, writes about his father’s life before the Gaddafi regime.

My father is used to waiting.

In one form or another, he has spent 41 years doing just that. My earliest memories of my dad are of him sitting on the sofa glued to the TV, watching the news while my brother and I grew around him. In a room housed inside one of the many hotels that became our family’s temporary nest, life resembled that of a normal family’s for a few days. On occasion, in our home in London, he would appear and drift away like a spirit — something we learned to live with. In some ways, I think he was waiting for a glimmer on the horizon, a memory that had fallen deep inside him and hadn’t been seen since the fall of 1969. It’s as if his watch had stopped that September, and like him, it waited for time worth telling to resume.

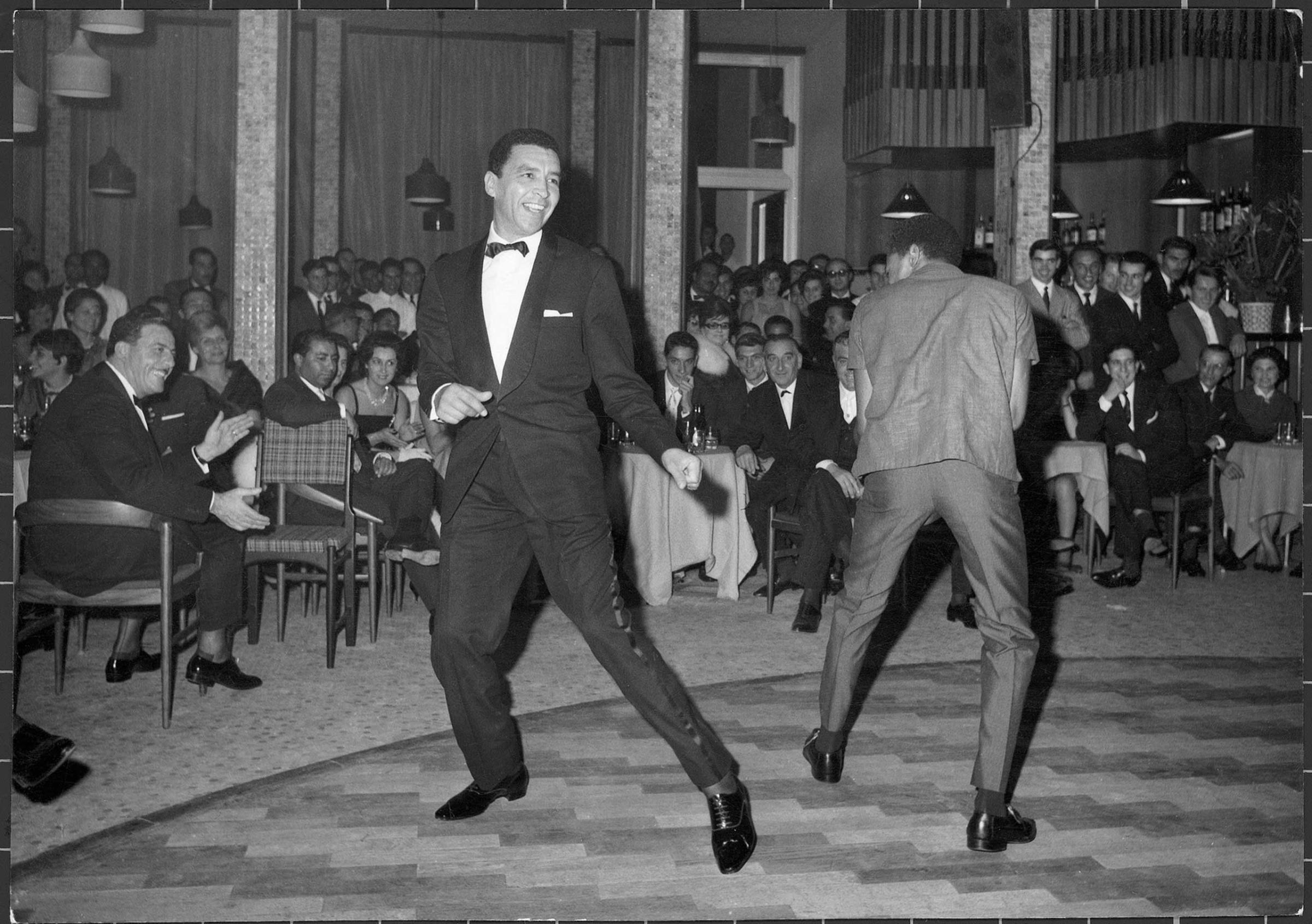

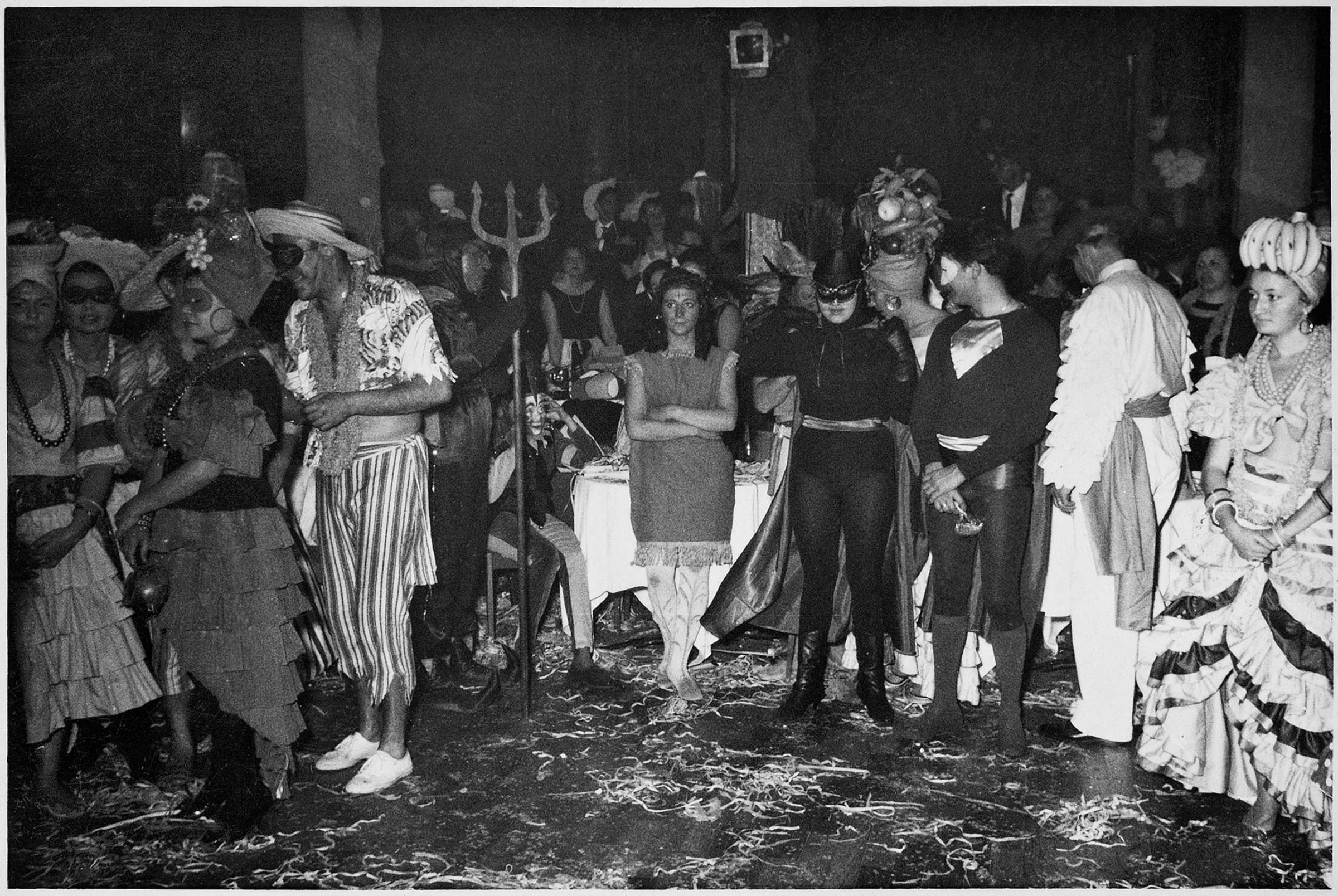

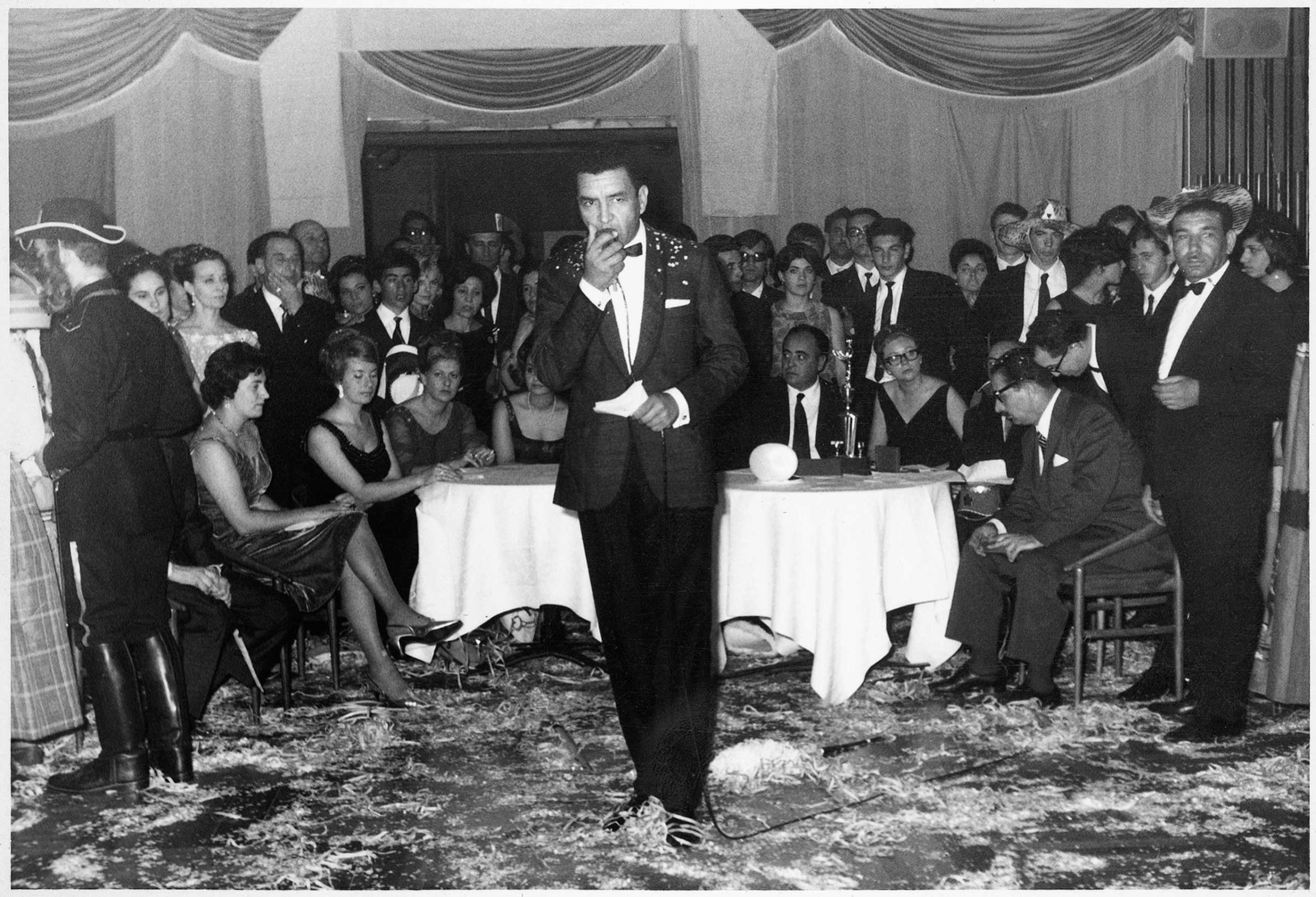

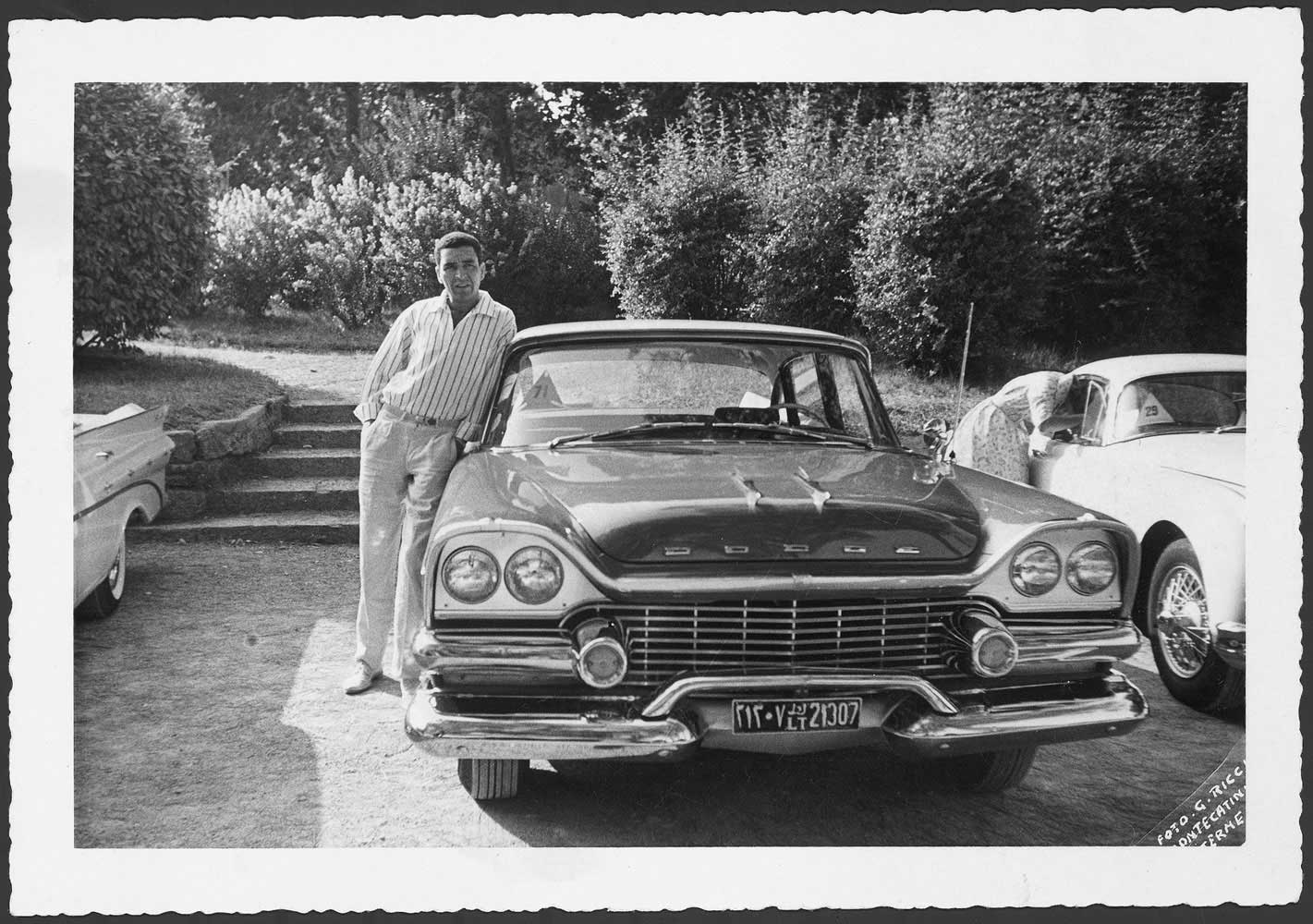

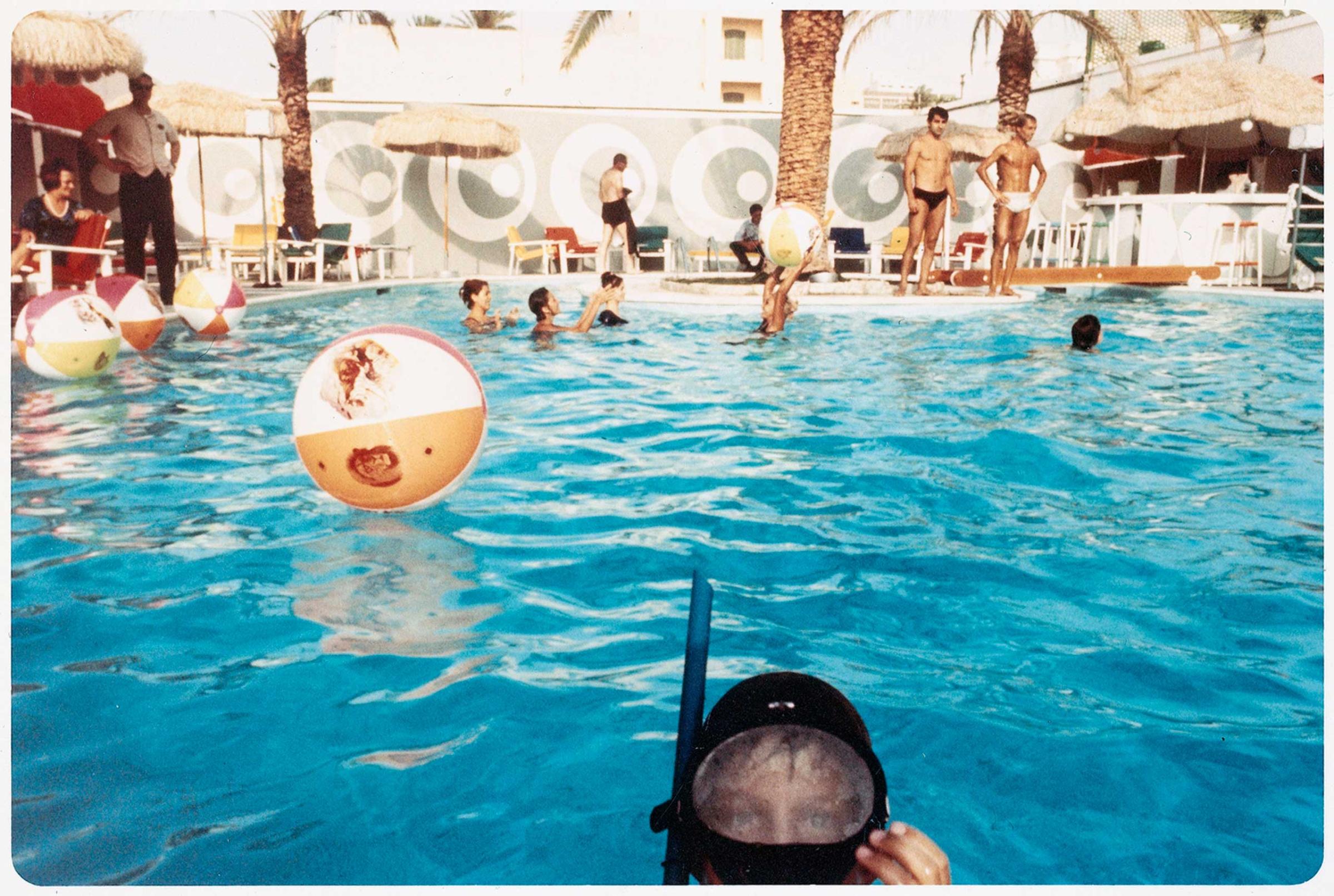

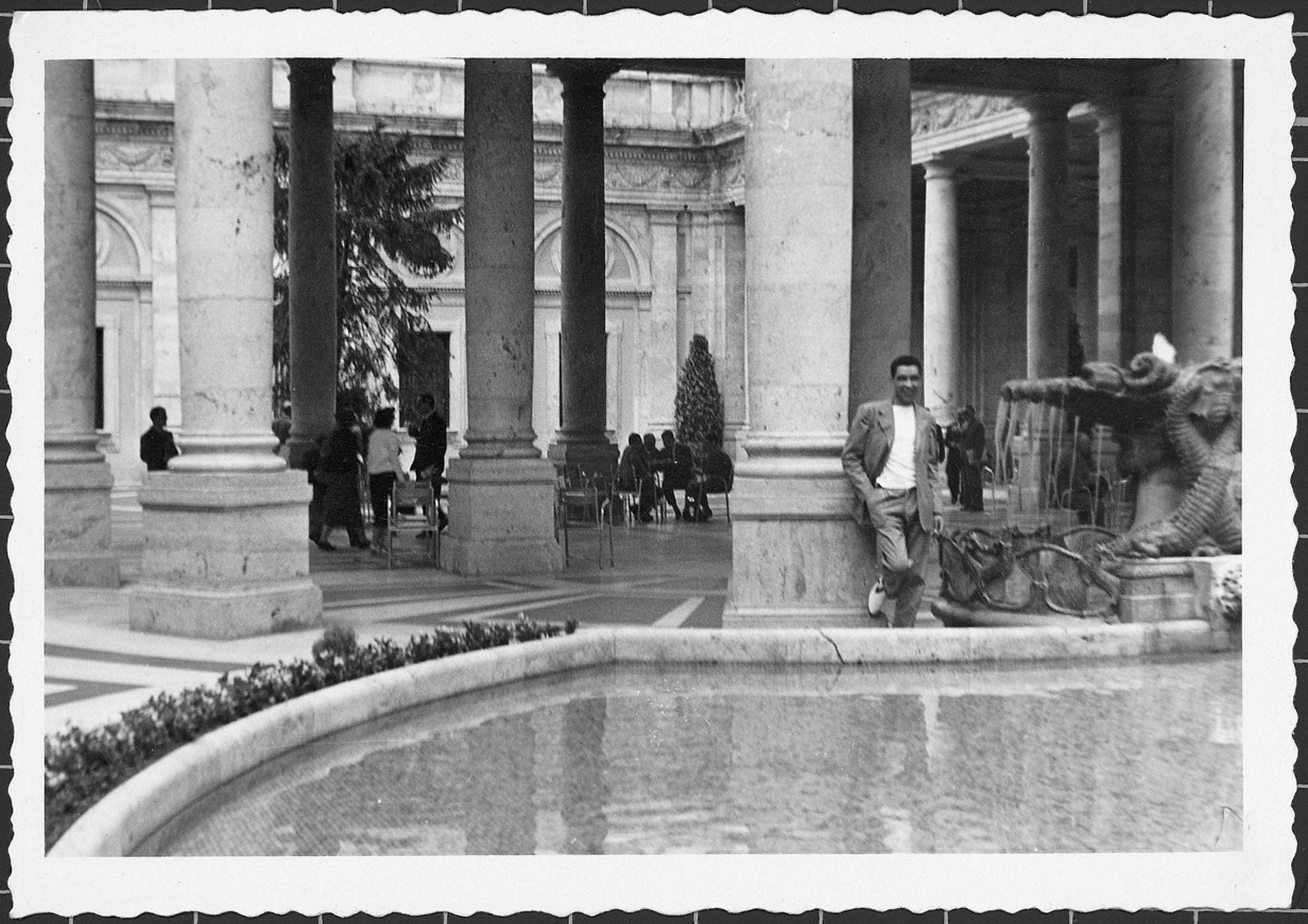

In the 1960s, my father was the owner of a hotel and casino named the Uaddan, which overlooked the coast in Tripoli. In my early years, I remember hearing stories of life inside the hotel before Muammar Gaddafi spearheaded the September revolution of 1969. As I got older, I began to see a pattern in the stories my father told. Seldom did he reminisce about moments that postdated his ownership of the Uaddan or share experiences that included my family. The birth of my brother or our family trips to various islands never made the cut. Nor did he talk much about the years he spent with my mother or how they met. My brother and I always joked that it were as if my father didn’t have the ability to record time that came after the hotel — I think there’s some truth in that.

What I have learned over the years is that to my father, the Uaddan was no longer a hotel but rather a demarcation for a period when his light glowed the strongest. The allure to return to those times never lost its potency. He lamented the loss of that light and would spend the next four decades lost in reveries that brought him closer to those days.

My relationship with Libya has always been mixed. To me, the country, and especially Tripoli, played as active a role in our family dynamic as any of us did. It was also a source of friction after my brother and I grew up in the U.K. We had little to no attachment to Libya, though it was more our country than anywhere else. My father resented us for not having spent more time there, although he understood that we had to leave for our safety in the early 80s. A greater distance developed between father and son because I had trouble relating to the life in Libya he held so close.

I think most Libyans who were around during those days have their own Uaddan — a safe house built for the purpose of storing away those memories and desires beneath the surface, locked away and preserved until a time would come when they could be ignited into flight.

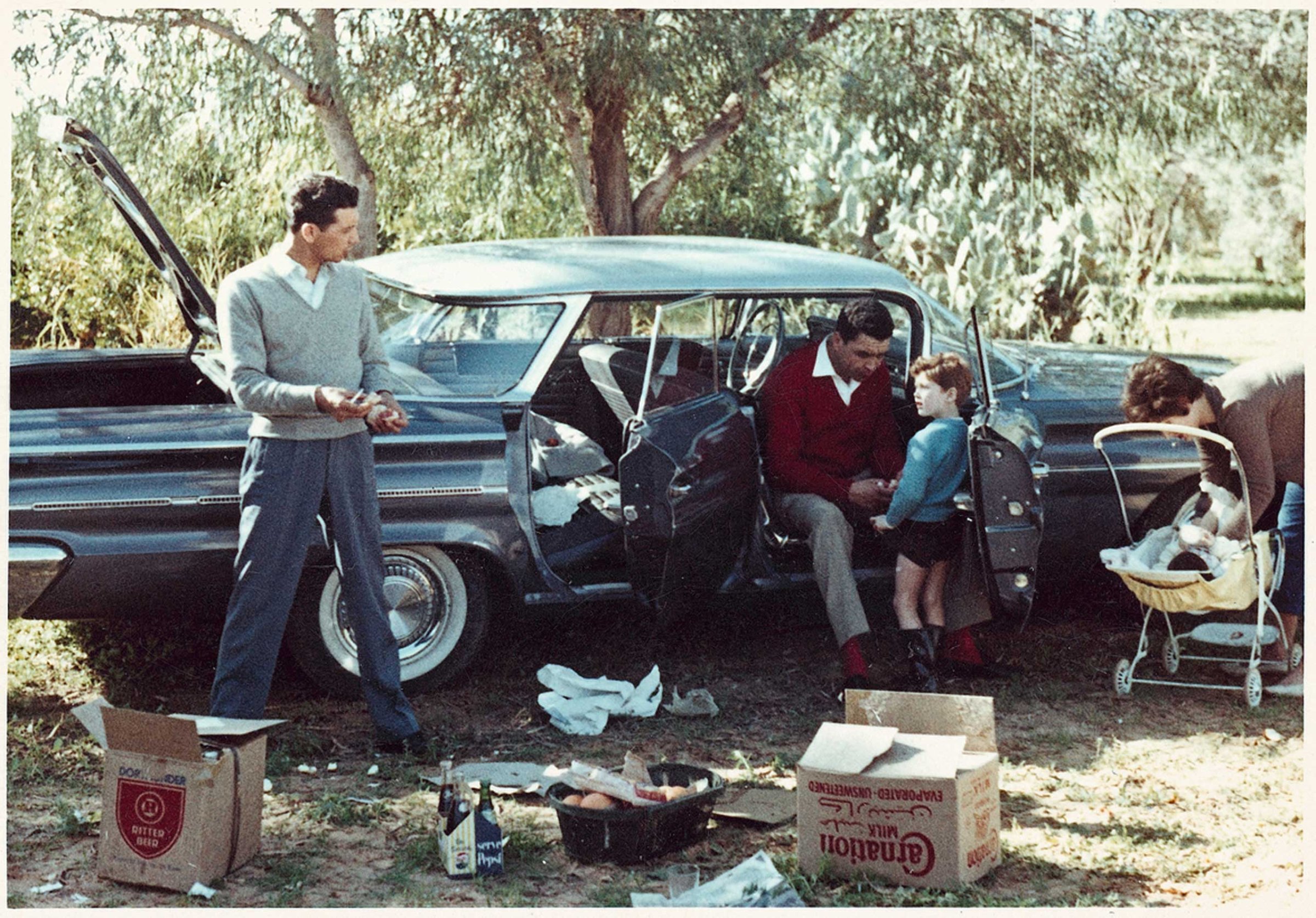

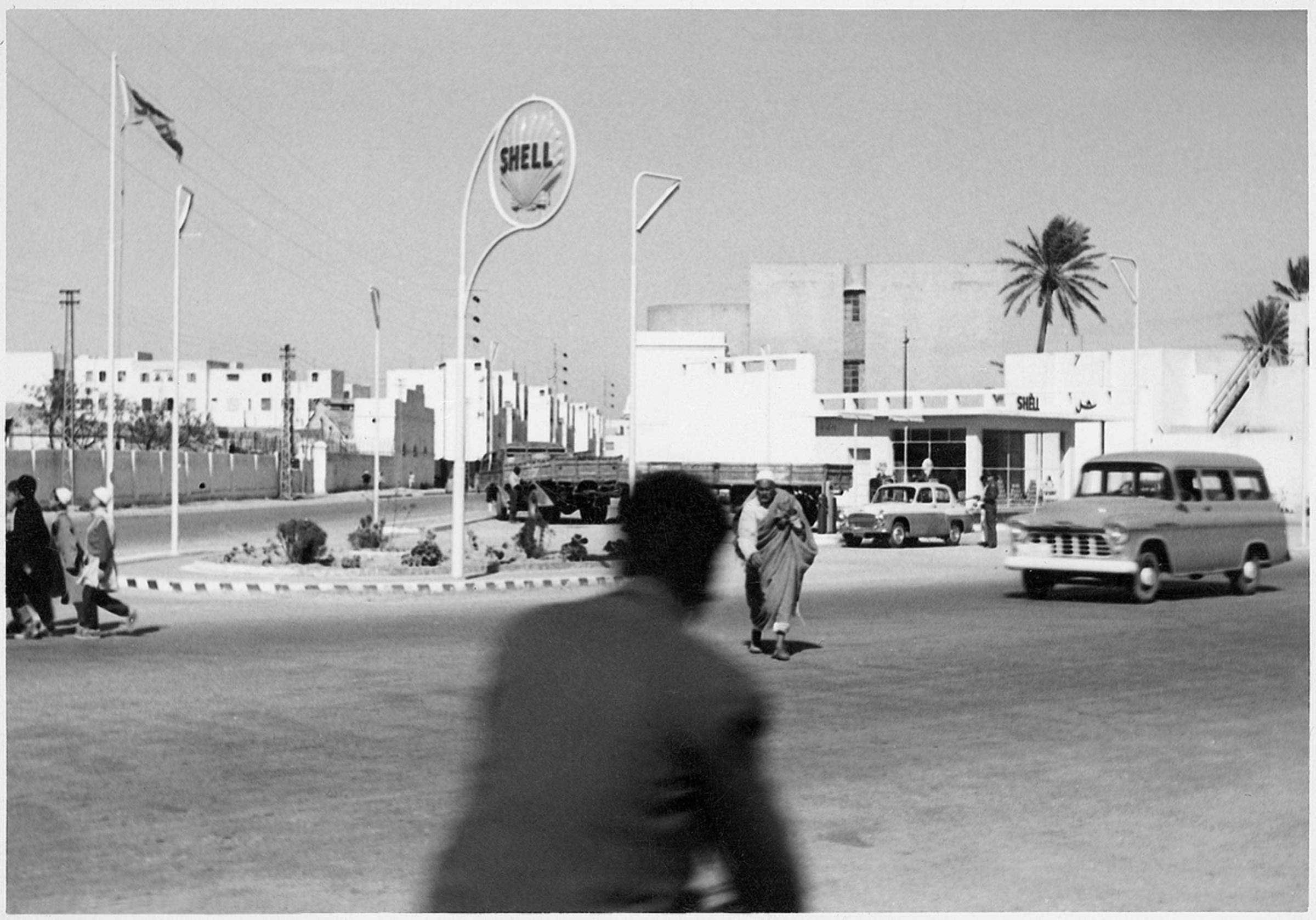

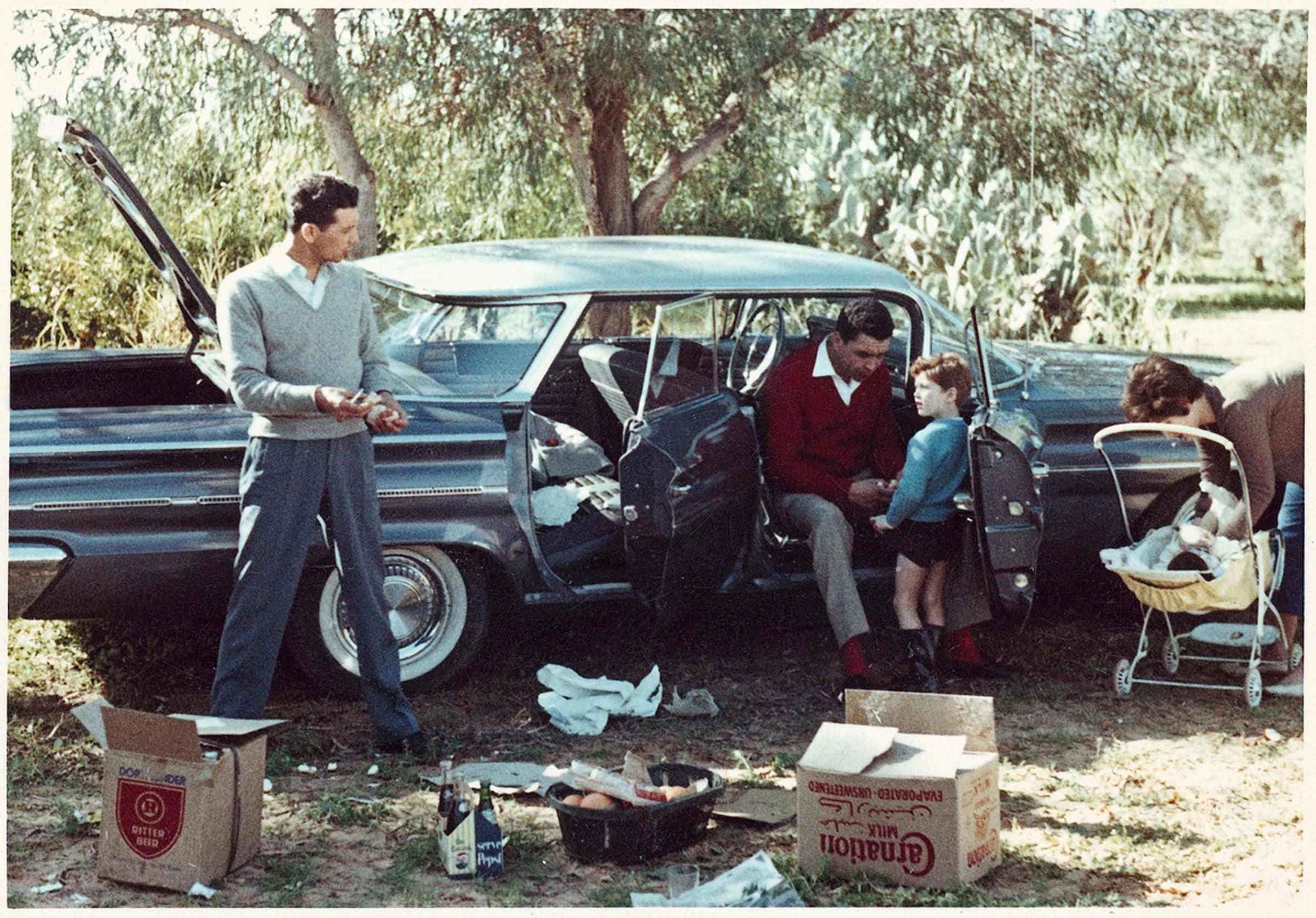

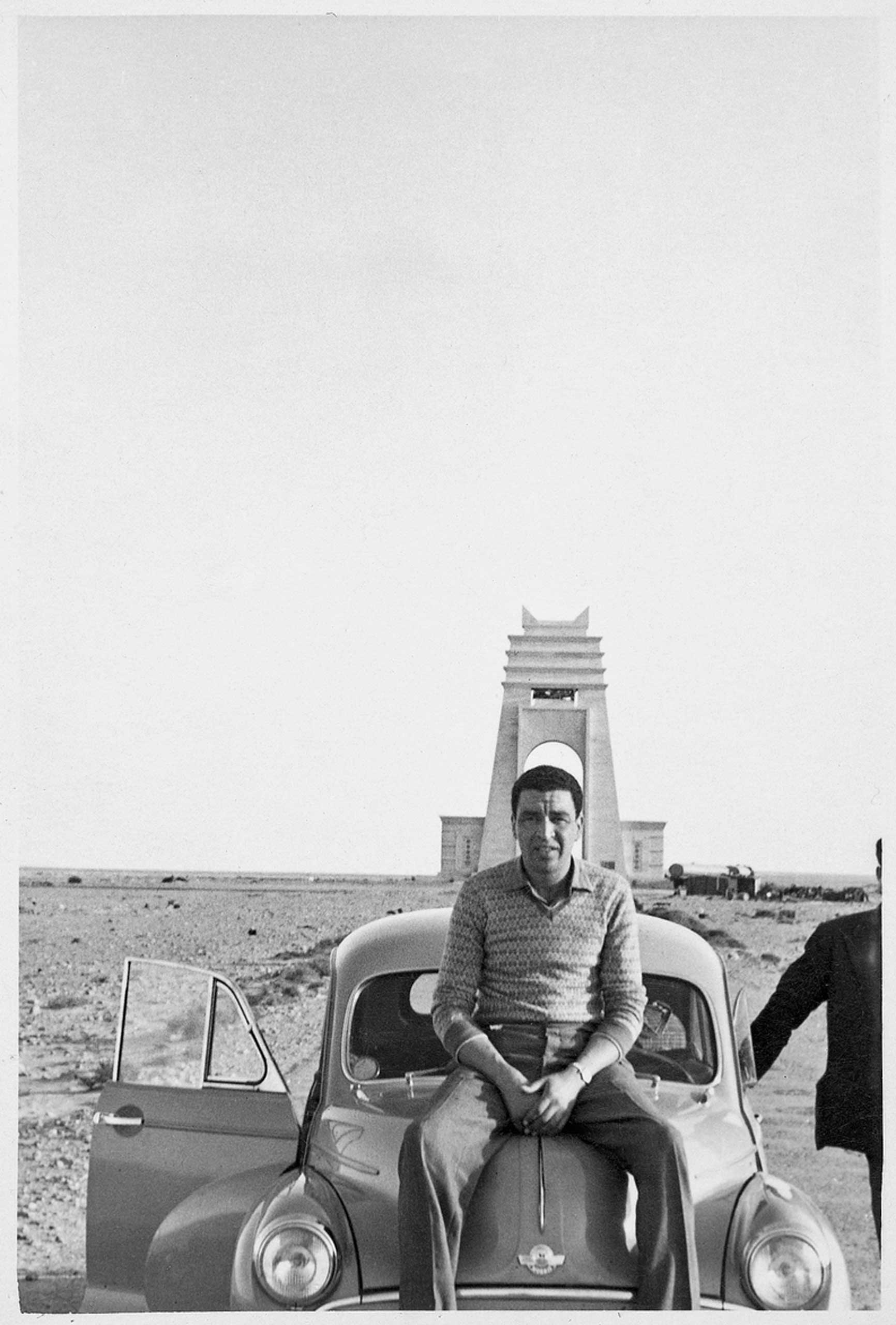

I always knew that Libya was not a camera culture. On my many trips back to Tripoli, I never saw people taking photos. My father never bothered to take photos after 1969 in the same way he used to. Those earlier days were recorded diligently: parties and beach trips and everyday life. The colors that once jumped out of the pictures from those days are now washed away and faded. I have spent a lot of time looking at these photos over the years. Now more than ever, they speak to me and give me a clear picture of what was extinguished for so many in 1969. Those chapters hold such an important role in the lives of not only the Libyans but also many of the internationals who were living in Tripoli at the time. My mother worked in Libya in 1969 as a schoolteacher and still talks fondly about those days, in the same way that people speak of the 1960s in the U.S.

To my father, the Uaddan was orphaned rather than simply taken by Gaddafi’s government. He knew that nobody would love or care for the place as much as he had all those years. The government had no use for the building and allowed it to succumb to the effects of long-term neglect. I have visited the hotel several times over the past few years, less out of curiosity than a need to see for myself the place that had taken on a life of mythological proportions in my upbringing. Still a hotel — although more a lifeless shell of what it once was — I never saw anyone inside during my visits. My father refused to go because I think it would have broken his heart to see its condition. To him, the hotel was sacred and forever preserved in his mind at its prime. My father’s memories of the Uaddan burst the actual boundaries of the building. He made it into something it may never quite have been — at least not as he boasted. But that’s what happens to memories: they become what you need them to be. Who he was during the Uaddan days, and what was taken from him with the coming of Gaddafi, would pull apart anyone. And into that chasm poured memories that have solidified to make up his past.

The events that have been taking place in Libya over these past months have brought me closer to understanding my father’s past than any events in the previous 30 years. As the revolt grew stronger in February and March, I began to see that hidden place inside him that he had never revealed to his children. When I saw him last month, it were as if his cheeks had become sun-kissed by the new dawn rising over Libya. He speaks of those days of the Uaddan as once again being within reach — his voice tells me that this is the moment he has been waiting for. He is again ready to take center stage on the ballroom floor and play host.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com