About a decade ago, Russian doctors began to notice strange wounds on the bodies of some drug addicts—patches of flesh turning dark and scaly, like a crocodile’s—in the hospitals of Siberia and the Russian Far East. It didn’t take them long to discover the cause: the patients had begun injecting a new drug they called, predictably, “krokodil.” (Some accounts suggest the name was derived from one of the drug’s precursor chemicals, alpha-chlorocodide.) Videos showing the effects of the “flesh-eating” drug—christened desomorphine when it was invented for medical use in 1932—quickly went viral online. There are now alarming stories that the monster could be at large in the U.S.

American drug-enforcement officials say fears of an imminent krokodil epidemic are overblown. But it’s hard not to be frightened of a drug that leaves a reptilian mark on its victims. Especially when it is so easy to make: an addict can cook up krokodil using ingredients and tools bought from the local pharmacy and hardware store. The active ingredient, codeine, is a mild opiate sold over the counter in many countries. Users mix codeine with a brew of poisons such as paint thinner, hydrochloric acid and red phosphorus scraped from the strike pads on matchboxes. The result—a murky yellow liquid with an acrid stink—mimics the effect of heroin at a fraction of the cost. In Europe, for example, a dose of krokodil costs just a few dollars, compared with about $20 for a hit of heroin.

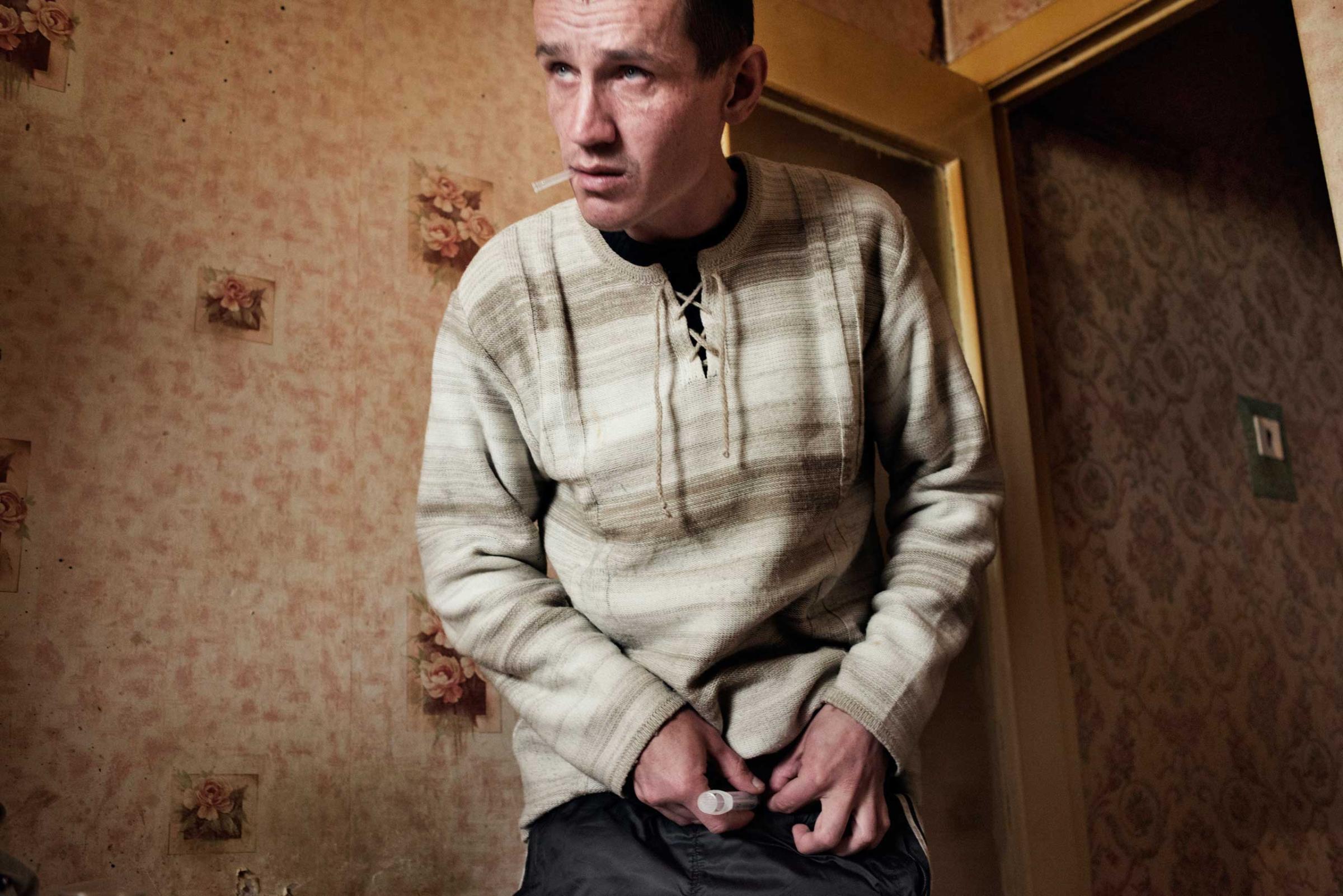

But addicts pay dearly for krokodil’s cheap high. Wherever on the body a user injects the drug, blood vessels burst and surrounding tissue dies, sometimes falling off the bone in chunks. That side effect has earned krokodil its other nickname: the zombie drug. The typical life span of an addict is just two or three years.

The drug quickly became popular among Russian addicts. In 2005, the country’s counternarcotics agency reported catching only “one-off” instances of the drug; six years later, in the first three months of 2011, the agency confiscated 65 million doses, up 23-fold from two years earlier. At its peak that year, krokodil use had spread to as many as a million addicts in Russia.

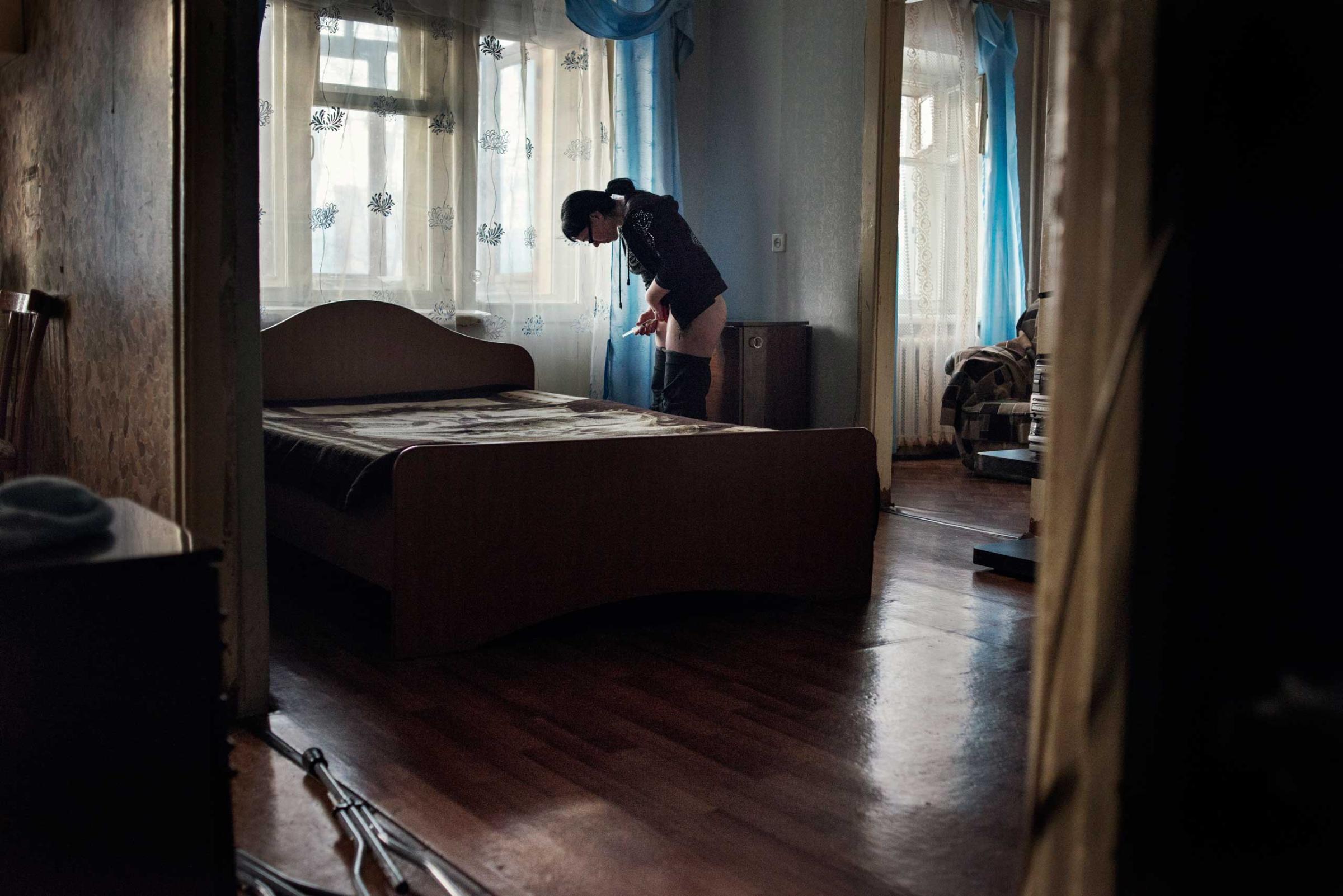

A ban on over-the-counter codeine sales that was introduced on June 1, 2012, has brought numbers down sharply, but Emanuele Satolli, an Italian photographer who has been chronicling a group of Russian addicts, says many now score that key ingredient on the black market. For the past year, Satolli has focused on the industrial city of Yekaterinburg in the Ural Mountains, a place notorious in Russia for drug abuse, photographing about a dozen krokodil addicts.

The krokodil epidemic may have peaked in Russia, but the drug’s use has already been reported elsewhere. In October, a report published online in the American Journal of Medicine confirmed the case of a 30-year-old addict in Richmond Heights, Mo., whose finger “fell off” and whose skin began to rot after he began injecting krokodil. The monster has crossed the ocean.

Emanuele Satolli is an Italian photojournalist based in Milan.

Simon Shuster is TIME’s Moscow correspondent. Follow him on Twitter @shustry.

Translation by Eugene Reznik.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com