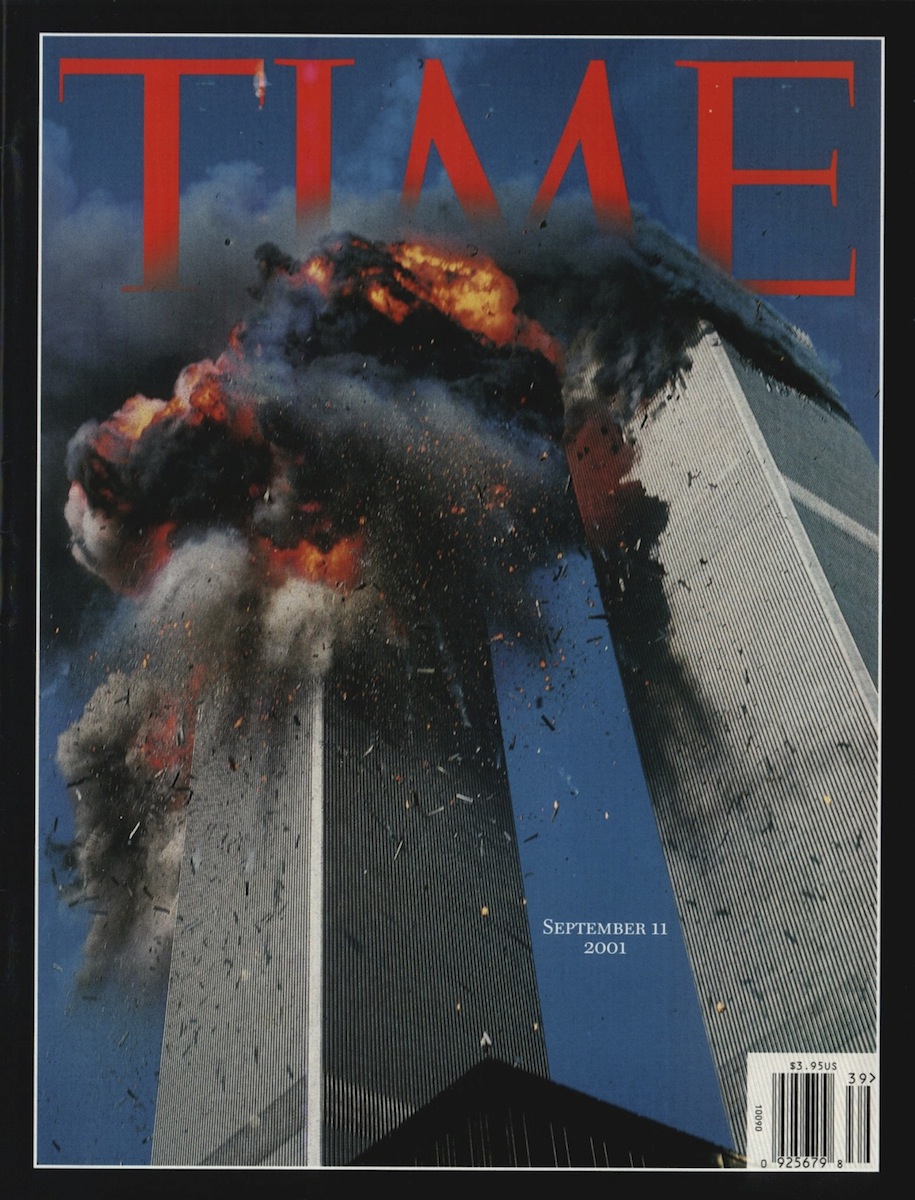

If you want to humble an empire it makes sense to maim its cathedrals. They are symbols of its faith, and when they crumple and burn, it tells us we are not so powerful and we can’t be safe. The Twin Towers of the World Trade Center, planted at the base of Manhattan island with the Statue of Liberty as their sentry, and the Pentagon, a squat, concrete fort on the banks of the Potomac, are the sanctuaries of money and power that our enemies may imagine define us. But that assumes our faith rests on what we can buy and build, and that has never been America’s true God.

On a normal day, we value heroism because it is uncommon. On Sept. 11, we valued heroism because it was everywhere. The fire fighters kept climbing the stairs of the tallest buildings in town, even as the steel moaned and the cracks spread in zippers through the walls, to get to the people trapped in the sky. We don’t know yet how many of them died, but once we know, as Mayor Rudy Giuliani said, “it will be more than we can bear.” That sentiment was played out in miniature in the streets, where fleeing victims pulled the wounded to safety, and at every hospital, where the lines to give blood looped round and round the block. At the medical-supply companies, which sent supplies without being asked. At Verizon, where a worker threw on a New York fire department jacket to go save people. And then again and again all across the country, as people checked on those they loved to find out if they were safe and then looked for some way to help.

This was the bloodiest day on American soil since our Civil War, a modern Antietam played out in real time, on fast-forward, and not with soldiers but with secretaries, security guards, lawyers, bankers, janitors. It was strange that a day of war was a day we stood still. We couldn’t move — that must have been the whole idea — so we had no choice but to watch. Every city cataloged its targets; residents looked at their skylines, wondering if they would be different in the morning. The Sears Tower in Chicago was evacuated, as were colleges and museums. Disney World shut down, and Major League Baseball canceled its games, and nuclear power plants went to top security status; the Hoover Dam and the Mall of America shut down, and Independence Hall in Philadelphia, and Mount Rushmore. It was as though someone had taken a huge brush and painted a bull’s-eye around every place Americans gather, every icon we revere, every service we depend on, and vowed to take them out or shut them down, or force us to do it ourselves.

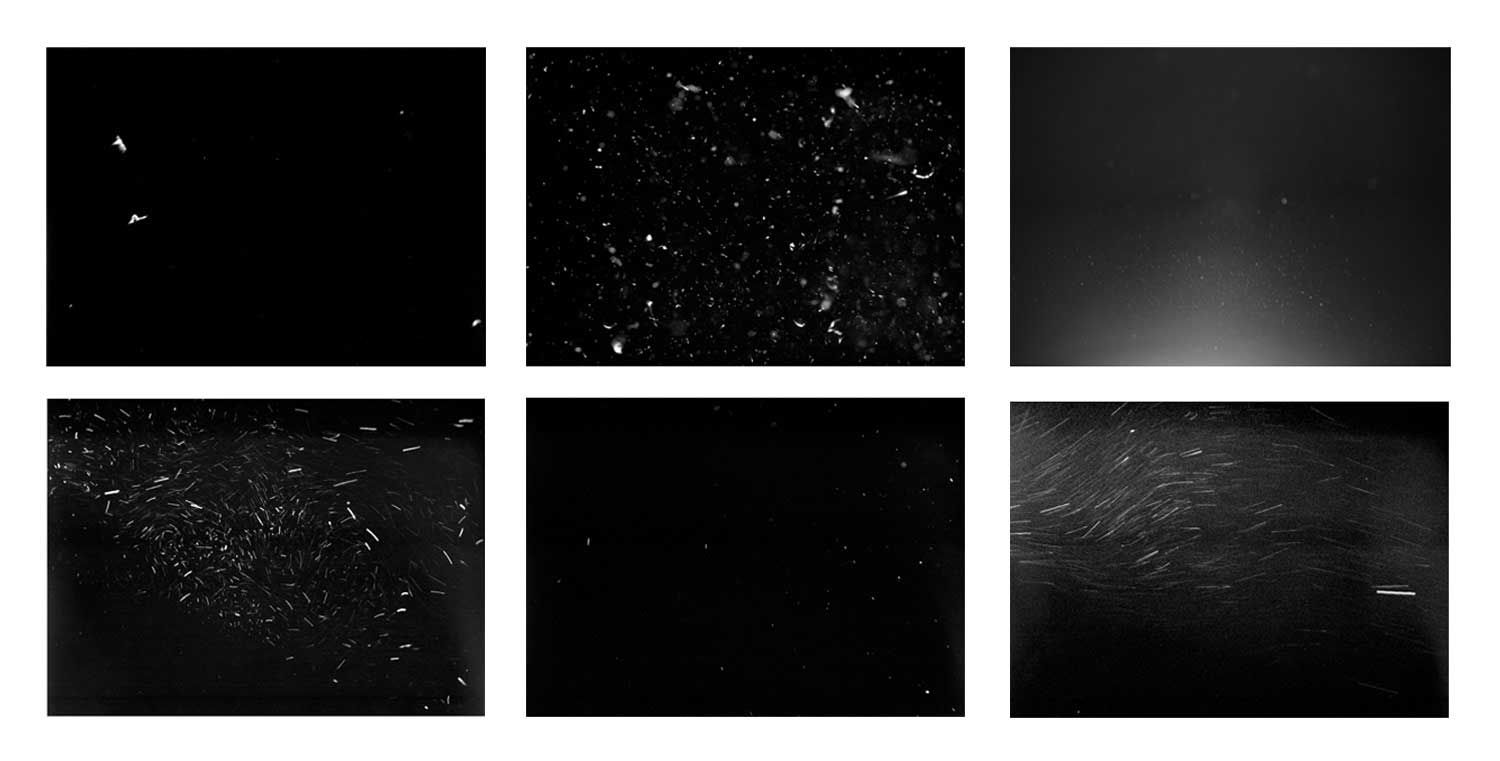

Revisiting 9/11: Unpublished Photos by James Nachtwey

Terror works like a musical composition, so many instruments, all in tune, playing perfectly together to create their desired effect. Sorrow and horror, and fear. The first plane is just to get our attention. Then, once we are transfixed, the second plane comes and repeats the theme until the blinding coda of smoke and debris crumbles on top of the rescue workers who have gone in to try to save anyone who survived the opening movements. And we watch, speechless, as the sirens, like some awful choir, hour after hour let you know that it is not over yet, wait, there’s more.

It was, of course, a perfect day, 70º and flawless skies, perfect for a nervous pilot who has stolen a huge jet and intends to turn it into a missile. It was a Boeing 767 from Boston, American Airlines Flight 11 bound for Los Angeles with 81 passengers, that first got the attention of air traffic controllers. The plane took off at 7:59 a.m. and headed west, over the Adirondacks, before taking a sudden turn south and diving down toward the heart of New York City. Meanwhile American Flight 757 had left Dulles; United Flight 175 left Boston at 7:58, and United Flight 93 left Newark three minutes later, bound for San Francisco. All climbed into beautiful clear skies, all four planes on transcontinental flights, plump with fuel, ripe to explode. “They couldn’t carry anything — other than an atom bomb — that could be as bad as what they were flying,” observed a veteran investigator.

The first plane hit the World Trade Center’s north tower at 8:45, ripping through the building’s skin and setting its upper floors ablaze. People thought it was a sonic boom, or a construction accident, or freak lightning on a lovely fall day; at worst, a horrible airline accident, a plane losing altitude, out of control, a pilot trying to ditch in the river and missing. But as the gruesome rains came — bits of plane, a tire, office furniture, glass, a hand, a leg, whole bodies, began falling all around — people in the streets all stopped and looked, and fell silent. As the smoke rose, the ash rained gently down, along with a whole lost flock of paper shuffling down from the sky to the street below, edges charred, plane tickets and account statements and bills and reports and volumes and volumes of unfinished business floating down to earth.

Almost instantly, a distant wail of sirens came from all directions, even as people poured from the building, even as a second plane bore down on lower Manhattan. Louis Garcia was among the first medics on the scene. “There were people running over to us burnt from head to toe. Their hair was burned off. There were compound fractures, arms and legs sticking out of the skin. One guy had no hair left on his head.” Of the six patients in his first ambulance run, two died on the way to St. Vincent’s Hospital.

The survivors of the first plot to bring down the Twin Towers, the botched attempt in 1993 that left six dead, had a great advantage over their colleagues. When the first explosion came, they knew to get out. Others were paralyzed by the noise, confused by the instructions. Consultant Andy Perry still has the reflexes. He grabbed his pal Nathan Shields from his office, and they began to run down 46 flights. With each passing floor more and more people joined the flow down the steps. The lights stayed on, but the lower stairs were filled with water from burst pipes and sprinklers. “Everyone watch your step,” people called out. “Be careful!” The smell of jet fuel suffused the building. Hallways collapsed, flames shot out of a men’s room. By the time they reached the lobby, they just wanted to get out — but the streets didn’t look any safer. “It was chaos out there,” Shields says. “Finally we ran for it.” They raced into the street in time to see the second plane bearing down. Even as they ran away, there were still people standing around in the lobby waiting to be told what to do. “There were no emergency announcements — it just happened so quickly nobody knew what was going on,” says Perry. “This guy we were talking to saw at least 12 people jumping out of [the tower] because of the fires. He was standing next to a guy who got hit by shrapnel and was immediately killed.” Workers tore off their shirts to make bandages and tourniquets for the wounded; others used bits of clothing as masks to help them breathe. Whole stretches of street were slick with blood, and up and down the avenues you could hear the screams of people plunging from the burning tower. People watched in horror as a man tried to shimmy down the outside of the tower. He made it about three floors before flipping backward to the ground.

Architect Bob Shelton had his foot in a cast; he’d broken it falling off a curb two weeks ago. He heard the explosion of the first plane hitting the north tower from his 56th-floor office in the south tower. As he made his way down the stairwell, his building came under attack as well. “You could hear the building cracking. It sounded like when you have a bunch of spaghetti, and you break it in half to boil it.” Shelton knew that what he was hearing was bad. “It was structural failure,” Shelton says. “Once a building like that is off center, that’s it.” “There was no panic,” he says of his escape down the stairs. “We were working as a team, helping everyone along the way. Someone carried my crutches, and I supported myself on the railing.”

Gilbert Richard Ramirez works for BlueCross BlueShield on the 20th floor of the north tower. After the explosion he ran to the windows and saw the debris falling, and sheets of white building material, and then something else. “There was a body. It looked like a man’s body, a full-size man.” The features were indistinguishable as it fell: the body was black, apparently charred. Someone pulled an emergency alarm switch, but nothing happened. Someone else broke into the emergency phone, but it was dead. People began to say their prayers.

“Relax, we’re going to get out of here,” Ramirez said. “I was telling them, ‘Breathe, breathe, Christ is on our side, we’re gonna get out of here.'” He prodded everyone out the door, herding stragglers. It was an eerie walk down the smoky stairs, a path to safety that ran through the suffering. They saw people who had been badly burned. Their skin, he says, “was like a grayish color, and it was like dripping, or peeling, like the skin was peeling off their body.” One woman was screaming. “She said she lost her friend, her friend went out the window, a gust sucked her out.” As they descended, they were passed by fire fighters and rescue workers, panting, pushing their way up the stairs in their heavy boots and gear. “At least 50 of them must have passed us,” says Ramirez. “I told them, ‘Do a good job.'” He pauses. “I saw those guys one time, but they’re not gonna be there again.” When he got outside to the street there were bodies scattered on the ground, and then another came plummeting, and another. “Every time I looked up at the building, somebody was jumping from it. Like from 107, Windows on the World. There was one, and then another one. I couldn’t understand their jumping. I guess they couldn’t see any hope.”

The terror triggered other reactions besides heroism. Robert Falcon worked in the parking garage at the towers: “When the blast shook it went dark and we all went down, and I had a flashlight and everyone was screaming at me. People were ripping my shirt to try and get to my flashlight, and they were crushing me. The whole crowd was on top of me wanting the flashlight.”

9/11: The Photographs That Moved Them Most

Michael Otten, an assistant vice president at Mizuho Capital Markets, was headed down the stairs around the 46th floor when the announcement came over the loudspeakers that the south tower was secure, people could go back to their desks or leave the building. He proceeded to the 44th floor, an elevator-transfer floor. One elevator loaded up and headed down, then came back empty, so he and a crowd of others piled in. One man’s backpack kept the doors from closing. The seconds ticked by. “We wanted to say something, but the worst thing you can do is go against each other, and just as I thought it was going to close, it was about 9:00, 9:03, whenever it was that the second plane crashed into the building. The walls of the elevator caved in; they fell on a couple people.” Otten and others groped through the dust to find a stairway, but the doors were locked. Finally they found a clearer passage, found a stairway they could get into and fled down to the street.

Even as people streamed down the stairs, the cracks were appearing in the walls as the building shuddered and cringed. Steam pipes burst, and at one point an elevator door burst open and a man fell out, half burned alive, his skin hanging off. People dragged him out of the elevator and helped get him out of the building to the doctors below. “If I had listened to the announcement,” says survivor Joan Feldman, “I’d be dead right now.”

Felipe Oyola and his wife Adianes did listen to the announcement. When Oyola heard the first explosion in his office on the 81st floor of the south tower, he raced down to the 78th floor to find her. They met at the elevator bank; she was terrified. But when the announcement came over the loudspeaker that the tower was safe, they both went back to work. Oyola was back on 81 when the second plane arrived. “As soon as I went upstairs, I looked out the window, and I see falling debris and people. Then the office was on top of me. I managed to escape, and I’ve been looking for my wife ever since.”

United Flight 175 left Boston at 7:58 a.m., headed to Los Angeles. When it passed the Massachusetts-Connecticut border, it made a 30-degree turn, and then an even sharper turn and swooped down on Manhattan, between the buildings, to impale the south tower at 9:06. This plane seemed to hit lower and harder; maybe that’s because by now every camera in the city was trained on the towers, and the crowds in the street, refugees from the first explosion, were there to see it. Desks and chairs and people were sucked out the windows and rained down on the streets below. Men and women, cops and fire fighters watched and wept. As fire and debris fell, cars blew up; the air smelled of smoke and concrete, that smell that spits out of jackhammers chewing up pavement. You could taste the air more easily than you could breathe it.

P.S. 89 is an elementary school just up the street; most of the families live and work in the financial district, and when bedlam broke, mothers and fathers ran toward the school, sweat pouring off them, frantic to get to their kids. Some people who didn’t know if their spouse had survived met up at school, because both parents went straight to the kids. “I just wanted to find my kids and my wife and get the hell off this island,” said one father. And together they walked, he and his wife and young son and daughter, 60 blocks or so up to Grand Central and safety.

The first crash had changed everything; the second changed it again. Anyone who thought the first was an accident now knew better. This was not some awful, isolated episode, not Oklahoma City, not even the first World Trade Center bombing. Now this felt like a war, and the system responded accordingly; the emergency plans came out of the drawers and clicked one by one into place. The city buckled, the traffic stopped, the bridges and tunnels were shut down at 9:35 as warnings tumbled one after another; the Empire State Building was evacuated, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the United Nations. First the New York airports were closed, then Washington’s, and then the whole country was grounded for the first time in history.

At the moment the second plane was slamming into the south tower, President Bush was being introduced to the second-graders of Emma E. Booker Elementary in Sarasota, Fla. When he arrived at the school he had been whisked into a holding room: National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice needed to speak to him. But he soon appeared in the classroom and listened appreciatively as the children went through their reading drill. As he was getting ready to pose for pictures with the teachers and kids, chief of staff Andy Card entered the room, walked over to the President and whispered in his right ear. The President’s face became visibly tense and serious. He nodded. Card left and for several minutes the President seemed distracted and somber, but then he resumed his interaction with the class. “Really good readers, whew!” he told them. “These must be sixth-graders!”

Meanwhile, in the room where Bush was scheduled to give his remarks, about 200 people, including local officials, school personnel and students, waited under the hot lights. Word of the crash began to circulate; reporters called their editors, but details were sparse — until someone remembered there was a TV in a nearby office. The President finally entered, about 35 minutes late, and made his brief comments. “This is a difficult time for America,” he began. He ordered a massive investigation to “hunt down the folks who committed this act.” Meanwhile the bomb dogs took a few extra passes through Air Force One, and an extra fighter escort was added. But the President too was going to have trouble getting home.

Even as the President spoke, the second front opened. Having hit the country’s financial and cultural heart, the killers went for its political and military muscles. David Marra, 23, an information-technology specialist, had turned his BMW off an I-395 exit to the highway just west of the Pentagon when he saw an American Airlines jet swooping in, its wings wobbly, looking like it was going to slam right into the Pentagon: “It was 50 ft. off the deck when he came in. It sounded like the pilot had the throttle completely floored. The plane rolled left and then rolled right. Then he caught an edge of his wing on the ground.” There is a helicopter pad right in front of the side of the Pentagon. The wing touched there, then the plane cartwheeled into the building.

Two minutes later, a “credible threat” forced the evacuation of the White House, and eventually State and Justice and all the federal office buildings. Secret Service officers had automatic weapons drawn as they patrolled Lafayette Park, across from the White House. Police-car radios crackled with reports that rogue airplanes had been spotted over the White House. The planes turned out to be harmless civilian aircraft that air-traffic controllers at National Airport were scrambling to help land so they could clear the air space over the nation’s capital.

But that was not all; there was a third front as well. At 9:58 the Westmoreland County emergency-operations center, 35 miles southeast of Pittsburgh, received a frantic cell-phone call from a man who said he was locked in the rest room aboard United Flight 93. Glenn Cramer, the dispatch supervisor, said the man was distraught and kept repeating, “We are being hijacked! We are being hijacked!” He also said this was not a hoax, and that the plane “was going down.” Said Cramer: “He heard some sort of explosion and saw white smoke coming from the plane. Then we lost contact with him.”

The flight had taken off at 8:01 from Newark, N.J., bound for San Francisco. But as it passed south of Cleveland, Ohio, it took a sudden, violent left turn and headed inexplicably back into Pennsylvania. As the 757 and its 38 passengers and seven crew members blew past Pittsburgh, air-traffic controllers tried frantically to raise the crew via radio. There was no response.

Forty miles further down the new flight path, in rural Somerset County, Terry Butler, 40, was pulling the radiator from a gray 1992 Dodge Caravan at the junkyard where he works. He had been watching the news and knew all flights were supposed to be grounded. He was stunned when he looked up in the sky and saw Flight 93 cutting through the lingering morning fog. “It was moving like you wouldn’t believe,” he said.

The rogue plane soared over woodland, cattle pastures and cornfields until it passed over Kelly Leverknight’s home. She too was watching the news. Her husband, on his regular tour of duty with the Air National Guard’s 167th Airlift Wing in Martinsburg, W.Va., had just called to reassure his wife that his base was still operating normally when she heard the plane rush by. “It was headed toward the school,” she said, the school where her three children were.

Had Flight 93 stayed aloft a few seconds longer, it would have plowed into Shanksville-Stonycreek School and its 501 students, grades K through 12. Instead, at 10:06 a.m., the plane smashed into a reclaimed section of an old coal strip mine. The largest pieces of the plane still extant are barely bigger than a telephone book. “I just keep thinking — two miles,” said elementary principal Rosemarie Tipton. “There but for the grace of God — two miles.”

CIA Director George Tenet was having a leisurely breakfast with his mentor, former Senator David Boren, at the St. Regis Hotel, when he got the news. Their omelettes had just arrived when Tenet’s security detail descended with a cell phone. “Give me the quick summary,” Tenet said calmly into the phone. He listened a few moments, and then told Boren: “The World Trade Center has been hit. We’re pretty sure it wasn’t an accident. It looks like a terrorist act.” He then got back to the phone, named a dozen people he wanted summoned to the CIA situation room. “Assemble them in 15 minutes,” he said. “I should almost be there by then.”

Vice President Dick Cheney was in his West Wing office when the Secret Service burst in, physically hurrying him out of the room. “We have to move; we’re moving now, Sir; we’re moving,” the agents said as they took him to a bunker on the White House grounds. Once there, with members of the National Security staff and Administration officials, they told Cheney that a plane was headed for the White House. Mrs. Cheney and Laura Bush were brought in as well. Staff members in the Old Executive Office Building, across the street from the White House, were huddled in front of their TV screens when they heard from TV reporters that they were being evacuated. Then the tape loop began. “The building is being evacuated. Please walk to the nearest exit.” “The looks were stone-faced,” a staff member to the Vice President said. “They were just zombies,” said another.

Senator Patrick Leahy of Vermont was heading to the Supreme Court Building to speak to a group of appellate judges. He had already heard the news from New York City. As he walked into the court building, he heard a muffled boom outside. It was the plane attacking the Pentagon. “I’ve got to tell you before we start there’s some horrible, horrible news coming in,” Leahy told the roomful of judges. By the time he was leaving the building, there were already 20 cops surrounding it. As he neared the Russell Senate Office Building, a Capitol policeman walked up: “Senator, I don’t know if you want to go back to your office,” he warned. “They’re evacuating the buildings.”

“I’ve got a lot of staff still working there,” Leahy snapped. “I’m not going to leave them in the building.”

Washington was supposed to have contingency plans for disasters like this, but the chaos on the streets was clear evidence that plans still needed work. By 10:45 a.m. the downtown streets around the Capitol, government buildings and White House were laced with cars pointing in every direction, unable to move. A security officer for one of the buildings sat on a park bench. He had been locked out of his building, so he didn’t have a clue if the senior officials inside were out and in a safe place. “I’m not surprised at this,” he said. “We aren’t prepared. We were supposed to have a plan to evacuate our Cabinet officer to a place 50 miles out, but none of that has been done.” Capitol police were slow to move as well. There was no increased security, no heightened alert around the Capitol for fully half an hour after the New York attack. Senate minority leader Trent Lott was drafting a press release to condemn the attack when he looked outside his window and saw black smoke billowing up from across the Potomac. He didn’t wait for an evacuation order. He gathered up his top staff and security detail and headed out of the Capitol, shocked to find that tourists were still walking into the building while he was fleeing it.

Senator Robert Byrd, the Senate’s president pro tempore and fourth in line to the presidency, was put in a chauffeured car and driven to a safe house, as were Speaker Dennis Hastert and other congressional leaders. There were rumors flying that the fourth plane, the one that went down in Pennsylvania, had been headed for the Capitol or Camp David. The safe houses are scattered throughout the Washington, northern Virginia and southern Maryland area. The Secret Service has similar safe houses where they can take the Vice President and other top Administration officials as well. They are homes, offices, in some cases even fire stations, that have secure phones so that the leaders can still communicate.

By 11 A.M., the streets in Washington were gridlocked with people trying to get out. In a place that doesn’t tend to carpool, co-workers had stuffed themselves into available vehicles. Both the 14th Street Bridge and Arlington Memorial Bridge, leading to Virginia and past the Pentagon, had been closed, as were the airports and Union Station. On the corner of Constitution Avenue and 14th Street, day-care workers from the Ronald Reagan Building clutched frightened toddlers into a tight bunch. Hysteria was gripping the city: senior generals at the Pentagon phoned children and other relatives, warning them not to drink tap water for the next 36 hours. They feared reservoirs might be poisoned.

Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan was flying back to the U.S. from Switzerland when his airliner was ordered to turn back. He reached vice chairman Roger Ferguson by phone as soon as he could, and Ferguson coordinated contacts with Reserve banks and Governors both in Washington and around the country. The goal: to make sure U.S. banks would keep functioning.

Meanwhile, the mood on board Air Force One could not have been more tense. Bush was in his office in the front of the plane, on the phone with Cheney, National Security Adviser Rice, FBI director Robert Mueller and the First Lady. Cheney told him that law-enforcement and security agencies believed the White House and Air Force One were both targets. Bush, the Vice President insisted, should head to a safe military base as soon as possible. White House staff members, Air Force flight attendants and Secret Service agents all were subdued and shaken. One agent sadly reported that the Secret Service field office in New York City, with its 200 agents, was located in the World Trade Center. The plane’s TV monitors were tuned in to local news broadcasts; Bush was watching as the second tower collapsed. About 45 minutes after takeoff, a decision was made to fly to Offut Air Force Base in Nebraska, site of the nation’s nuclear command and one of the most secure military installations in the country. But Bush and his aides didn’t want to wait that long before the President could make a public statement. Secret Service officials and military advisers in Washington consulted a map and chose a spot for Bush to make a brief touchdown: Barksdale Air Force Base, outside of Shreveport, La. In Bush’s airborne office, aides milled about while Bush spoke on the phone. “That’s what we’re paid for, boys,” he said. “We’re gonna take care of this. We’re going to find out who did this. They’re not going to like me as President.” The handful of reporters aboard were told not to use their cell phones — and not even to turn them on — because the signals might allow someone to identify the plane’s location.

Air Force One landed at Barksdale at 11:45 a.m., with fighter jets hovering beside each wing throughout the descent. The perimeter was surrounded by Air Force personnel in full combat gear: green fatigues, flak jackets, helmets, M-16s at the ready. The small motorcade traveled to Building 245. A sign on the glass windows of several doors, in large black type, read DEFCON DELTA. That is the highest possible state of military alert. Bush made his second remarks at 12:36 from a windowless conference room, in front of two American flags dragged together by Air Force privates. “Freedom itself was attacked this morning by a faceless coward,” he began, then spoke for two minutes before leaving the room.

In New York, the chaos was only beginning. Convoys of police vehicles raced downtown toward the cloud of smoke at the end of the avenues. The streets and parks filled with people, heads turned like sunflowers, all gazing south, at the clouds that were on the ground instead of in the sky, at the fighter jets streaking down the Hudson River. The aircraft carriers U.S.S. John F. Kennedy and U.S.S. George Washington, along with seven other warships, took up positions off the East Coast.

Jim Gartenberg, 35, a commercial real estate broker with an office on the 86th floor of 1 World Trade Center, kept calling his wife Jill to let her know he was O.K. but trapped. “He let us know he was stuck,” says Jill, who is pregnant with their second child. “He called several times until 10. Then nothing. He sounded calm, except for when he told me how much he loved me. He said, ‘I don’t know if I’ll make it.’ He sounded like he knew it would be one of the last times he would say he loved me.” That was right before the building turned to powder.

The tower’s structural strength came largely from the 244 steel girders that formed the perimeter of each floor and bore most of the weight of all the floors above. Steel starts to bend at 1000[degrees]. The floors above where the plane hit — each floor weighing millions of pounds — were resting on steel that was softening from the heat of the burning jet fuel, softening until the girders could no longer bear the load above. “All that steel turns into spaghetti,” explains retired ATF investigator Ronald Baughn. “And then all of a sudden that structure is untenable, and the weight starts bearing down on floors that were not designed to hold that weight, and you start having collapse.” Each floor drops onto the one below, the weight becoming greater and greater, and eventually it all comes down. “It didn’t topple. It came straight down. All floors are pancaking down, and there are people on those floors.”

The south tower collapsed at 10, fulfilling the prophecy of eight years ago, when last the terrorists tried to bring it down. The north tower came down 29 minutes later, crushing itself like a piston. “I know that the rescue people who were helping us didn’t get out of the building,” said security official Bill Heitman, who worked on the 80th floor. “I know they didn’t make it.” And he broke down and sobbed. All that was left of the New York skyline was a chalk cloud. The towers themselves were reduced to jagged stumps; the atrium lobby arches looked like a bombed out cathedral. “A huge plume of smoke was chasing people, rushing through those winding streets of lower Manhattan,” says Charlie Stuard, 37, an Internet consultant who works downtown. “It was chaos, a whiteout. That’s when people really started to panic. You could see it coming. A bunch of us jumped over a rail, onto the pilings on the East River, ready to jump in.”

The streets filled with masked men and women, cloth and clothing torn to tie across their noses and mouths against the dense debris rain. Some streets were eerily quiet. All trading had stopped on Wall Street, so those canyons were empty, the ash several inches thick and gray, the way snow looks in New York almost before it hits the ground. Sounds were both muffled and magnified, echoing off buildings, softened by the smoke. You could hear the chirping of the locator devices the fire fighters wear, hear the whistle of the respirators, see only the lights flashing red and yellow through the haze.

Major Reginald Mebane, who heads security for one of the state court buildings, organized a group of about 10 officers. They grabbed some medical equipment and hopped a court bus to help evacuate people. But when one tower began to collapse, they raced for cover inside Building Five of the Trade Center complex. The smoke made it so dark they could see only a few feet in front of them, even with flashlights. They felt their way along the walls and windows to get out. “The building just blew,” says Bill Faulkner, 53, a Vietnam veteran who was part of the group. “I would be dead if I hadn’t jumped behind a pillar.” Another court officer, Ed Kennedy, who also hid behind the pillar, says he grabbed the arm of a woman in an effort to pull her behind the pillar with him. But he didn’t grab her fast enough. Suddenly he realized he was holding just an arm. It was only when a fireman broke the window in the Borders bookstore that the men were able to escape.

Fire fighters pushed people further back, back up north. Mayor Giuliani took to the streets, walking through the raining dust and ordering people to evacuate the entire lower end of the island. Medical teams performed triage on the streetcorners of Tribeca, doling out medical supplies and tending the walking wounded. Doctors, nurses, EMTs, even lifeguards, were recruited to help. Volunteers with the least training were diverted to blood-donation centers or the dreaded “black teams,” where they would not be called upon to save a life, just handle dead bodies during triage. The color code: black for dead, red for immediately life-threatening wounds, yellow for serious, non-life threatening and green for the walking wounded. Police and fire fighters realized even as they worked that hundreds of their colleagues, the first to respond, were dead. Each looked as if someone had kicked him in the stomach. A looter was arrested: he had two fire department boots on his feet, and the cops looked as if they were going to kill him.

The refugee march began at the base of the island and wound up the highways as far as you could see, tens of thousands of people with clothes dusted, faces grimy, marching northward, away from the battlefield. There was not a single smile on a single face. But there was remarkably little panic as well — more steel and ingenuity: Where am I going to sleep tonight? How will I get home? “They can’t keep New Jersey closed forever,” a man said. Restaurant-supply companies on the Bowery handed out wet towels. A cement mixer drove toward the Queensboro Bridge with dozens of laborers holding onto it, hitching a ride out of town. Overcrowded buses, one after another, shipped New York’s workers north. Ambulances, some covered with debris, sped past them, ferrying the injured to the waiting hospitals.

All over the city, people walked with radios pinned to their ears. One man had the news on his car radio turned up as close to 100 people surrounded the car listening to the reports. Just before noon, a radio commentator said, “Inarguably, this is the worst day in the history of New York City.” No one argued.

Churches opened their sanctuaries for prayer services. St. Bartholomew’s offered water and lemonade to everyone passing by. The noon Mass at St. Patrick’s was nearly full. “We pray as we have never prayed before,” said Monsignor Ferry. “Remember the victims today. Forgive them their sins, and bring them into the light.” Posted defiantly in every window of one restaurant was the sign WE REFUSE TO GIVE IN TO TERRORISM. CIBO IS OPEN FOR BUSINESS. GOD BLESS AMERICA. A well-dressed man in a suit sat on a bench in Central Park, his head bowed, his hands clasped between his knees. A carousel of quiet toys turned in the darkened windows of FAO Schwarz.

There were no strangers in town anymore, only sudden friends, sharing names, news and phones. Lines formed, at least 20 people long, at all pay phones, because cell phones were not working. Should we go to work? Is the subway safe? “Let’s all have a good look at each other,” a passenger said to the others in her car. “We may be our last memory.” The passengers stranded at La Guardia Airport asked one another where exactly they were supposed to go and how they were to get there. Bridges, tunnels and ferries to Manhattan were not running. Strangers were offering each other a place to wait in Queens, giving advice on good diners in Astoria. Limousine drivers offered to take passengers to Boston for a price. A vendor dispensed free bottles of water to travelers waiting in the hot sun.

Dr. Ghoong Cheigh, a kidney specialist at New York Presbyterian Hospital, was handed an “urgent notice,” along with other arriving staff: “The disaster plan for New York Presbyterian Hospital is currently in effect, and an emergency command center has been established.” All elective surgeries were canceled, and any patient well enough to be discharged was released to make room for the incoming wounded. At Bellevue, the city’s largest trauma center, an extra burn unit was set up in the emergency room. The night shift was called in early. The psychiatric department staff, the biggest in the world, was mobilized to meet the survivors and families. “We actually have too many doctors now,” chief medical officer Eric Manheimer reported in midafternoon. “We thought we would have more patients.” By 5:40, only 159 patients had been admitted — which suggested not how few had been injured, but how few could be saved.

Security guards were turning all cars away from New York Weill Cornell Medical Center, allowing only emergency vehicles through. Around 10:40 a taxi pulled up, bearing three women and a man. Security tried to stop them, but a woman yelled, “We have a woman in labor here!” The guards waved them through.

At St. Vincent’s Hospital in Greenwich Village they were running out of Silvadene to treat burn victims, and began raiding the local drug stores. A hospital staff member wheeled around a grocery cart with a sign on the side reading, WE NEED CLOTHING DONATIONS. Within the hour, local residents had brought dozens of shopping bags full of blazers, shoes and pants, for patients whose clothes had been burned off. Edward Cardinal Egan led a team of priests to begin giving last rites. At one point he emerged from the emergency room, wearing blue hospital scrubs. His purple robes peeked out at the collar, and over one of his blue rubber gloves he had placed his enormous gold cardinal’s ring. He said, quite formally, “I am amazed at the goodness of our police and our fire fighters and our hospital people.”

When English teacher Karen Kriegel heard the news, she couldn’t just stay in her downtown office; she had to do something. So she printed up some handmade signs that said GIVE BLOOD NOW, photocopied them at a copy shop and headed for St. Vincent’s. As she started walking and handing out flyers, 100 people started walking with her. When they reached the hospital, the gurneys were everywhere, and rolling desk chairs covered with white sheets had been brought out to the pavement to handle bodies. The chairs already looked like ghosts.

Outside the N.Y. Blood Center, the line of prospective donors stretched halfway down the block, around the corner, all the way to 66th Street and around that corner — more than a thousand, all told. Type O donors, the universal donors, were handed little yellow movie tickets and asked to form a separate line. Eventually some blood centers turned everyone else away, told them to come back another day. “It’s just amazing,” said nurse Anne Taylor, standing in the donors’ line. “There’ll be a three- or four-hour wait, and just look at all of these people standing here. They can’t scare us.” Bellevue hospital had so many donors, it ran out of plastic bags.

The warlike mobilization was by no means left to the stricken zones. At Chalkville Elementary School near Birmingham, Ala., more than 700 calls had been received from worried parents, many of whom came at midmorning to pick up their children. Churches and schools and civic groups all around the country offered to help anyone stranded by the grounding of the nation’s planes. All over Los Angeles, offices and government buildings were shut down and surrounded by police: city hall, the Federal Building in Westwood, even shopping malls. At the Federal Building, armored rescue vehicles and Ford cars ringed the entrances and exits, with FBI staffers decked out in black and brandishing MP5 assault rifles. Even Express Mail trucks were searched by the FBI before they were allowed onto the premises. Gas pipeline companies were beefing up security at key transmission stations. Grand Coulee Dam in central Washington State was locked down. Gasoline stations around the country were running out of gas as motorists rushed to top off their tanks.

In Chicago, Steve Bernard was huddled around the TV with colleagues on the 36th floor of Chicago’s Sears Tower, shortly after 8 a.m., watching the smoke billowing from the World Trade Center after the first attack. When the second plane hit, bewilderment at a faraway spectacle turned into a much more personal, creeping panic. The Chicago staff of the Piper Jaffray investment firm suddenly redirected their gazes toward the windows, quietly searching for jets on their own horizon. The 110-story Sears Tower, even taller than the World Trade Center, is the tallest building in the U.S.; a vulnerable target. Bernard’s wife called him and insisted he come home. Within an hour, the building was evacuated.

Across the country, houses of all kinds of worship filled with grieving Americans singing America the Beautiful, wiping away streams of tears. “Humanity came apart in lower Manhattan today, and each of us is wounded. We mourn the loss of our innocence,” declared Rabbi Gary Gerson at Oak Park Temple, a Reform Jewish congregation outside Chicago. “Terror has struck us, but it will not destroy us. Now we are all Israelis,” he added.

Indeed, there were many Americans who refused to be intimidated by the tragedy, rightly or wrongly. They were reassuring, if not necessarily reasonable. The order to close the U.S. Courthouse in Little Rock, Ark., came shortly before 10 a.m., and it was promptly heeded by everyone except a solitary federal district judge. There sat Henry Woods, age 83, his lined face framed by a mane of white hair, beneath a replica of the seal of the U.S. Around him, at his insistence, a jury and lawyers carried on in a damage suit stemming from, of all things, a 1999 American Airlines crash. “This looks like an intelligent jury to me,” Woods said, explaining his refusal to grant a mistrial to the defense after getting word of the disaster. “And I didn’t want the judicial system interrupted by a terrorist act, no matter how horrible.”

If people all over the country had a sense of being suddenly at war — chat boards on Yahoo filled up with people wanting to volunteer for military service — it was with an enemy they could not see and not easily touch.

Meanwhile the U.S. government reassembled and mobilized. Secretary of State Colin Powell cut short his trip to Latin America to return to the U.S. By midafternoon, members of Congress were calling on their leaders to summon a special session, to show the world the government was up and running. About half of the Senate convened in a conference room at the Capitol Hill Police Station to hear from their leaders — some to vent their outrage at President Bush. Both Democrats and Republicans wanted to know, Where is he? Why isn’t he here? Why isn’t he in New York? Why isn’t he talking to the country? The answer: Bush had been told by the Secret Service, the military and the FBI that it was not yet safe to return to Washington. Only 24 hours later, after absorbing a wave of criticism for his delayed return, did aides claim there had been “credible evidence” that the White House and Air Force One were targets.

Some Republicans on the Hill wanted to know why Counsellor Karen Hughes was the highest government official anyone saw on television all day, other than Bush’s brief, unsettling appearance in Louisiana. They wanted to see Bush stride across the South Lawn and show that this is not a country that can be sent into hiding by cowards. “He better have the speech of his life ready tonight,” sighed one Republican strategist. Bush did return a few hours later, did stride across the South Lawn and did deliver a reasonably effective national address from the Oval Office. But it wasn’t until the following day that he stepped up the intensity of his rhetoric and declared the attacks “acts of war.”

Tucked inside the shock and fury was dismay at the performance of others whose job — perhaps impossible — was to prevent this from happening. There were quiet calls for the heads of CIA chief Tenet and FAA boss Jane Garvey for allowing so appalling a breach of security on their watch. And there was an equal determination to find those who were behind it.

Only God knows what kind of heroic acts took place at 25,000 feet as passengers and crews contended with four teams of highly trained enemy terrorists. But it is clear that the hunt for the culprits began way up in the sky, by the doomed passengers and crews themselves, minutes before the attacks took place. In their final goodbyes, on brief and haunting calls from their cell phones, the victims on board at least two of the four planes whispered the number and even some of the seat assignments of the terrorists. A flight attendant on board American Flight 11 called her airline’s flight operations center in Dallas on a special airlink line and reported that passengers were being stabbed.

That gave investigators a heads-up that something had gone terribly wrong, but there were plenty of other clues. Even before the smoke had cleared, it was obvious that the culprits knew their way around a Boeing cockpit — and all the security weaknesses in the U.S. civil aviation system. The enemy had chosen the quietest day of the week for the operation, when there would be fewer passengers to subdue; they had boarded westbound transcontinental flights — planes fully loaded with fuel. They were armed with knives and box cutters, had gained access to the cockpits and herded everyone to the back of the plane. Once at the controls, they had turned off at least one of the aircraft’s self-identifying beacons, known as transponders, a move that renders the planes somewhat less visible to air traffic controllers. And each aircraft had gone through dramatic but carefully executed course corrections, including a stunning last maneuver by Flight 77. The pilot of that plane came in low from south of the Pentagon, and pulled a 270[degree] turn before slamming into the west wall of the building.

And though everyone wanted to be prudent, there weren’t a lot of suspects to round up. Palestinian terror groups are experienced at suicide missions, but have never attempted an operation this large. Groups with links to the Iranian government took down the Khobar Towers in Saudi Arabia in 1996, killing 19, but that target was a long way from the U.S. Libya has lost its taste for terror, most experts believe, and Iraq’s Saddam Hussein has always favored loud, brutish force over quiet finesse. Besides, no group other than Osama bin Laden’s loose knit network of operatives in dozens of countries worldwide has ever shown the will, wallet or gall to attack the U.S. before. Bin Laden is responsible for the attacks on U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania. Three weeks ago when he told an Arab journalist he would mount an unprecedented attack on the U.S. “This was well funded and well planned,” said Senator Pat Roberts, who sits on the Senate Intelligence Committee. “It took a lot of planning. The weather had to be just so on the East Coast. They used sophisticated tactics where they hijacked planes, killed the crew, and they had to have aviators or navigators who knew what they were doing.”

Deputy Secretary of State Richard Armitage gathered his senior aides in the State Department’s seventh-floor secure facility shortly after 9 a.m. Tuesday for a videoconference with the Administration’s top national security aides. National Security Adviser Rice and her top counterterrorism coordinator Richard Clark were on one screen, with FBI Director Mueller and his senior aides, the CIA’s counterterrorism director, and FAA officials on others. Vice President Cheney was supposed to be in on the teleconference, but the Secret Service had already spirited him off to a safehouse. “We knew we were in trouble,” says one official who was present. “We’ve got suicide attacks here.”

Rice stayed silent as the meeting progressed; Clark did most of the talking. Finally at around 9:45 a.m., aides behind Mueller started murmuring and whispering into his ear. Mueller interrupted everyone. “The Pentagon has been hit by an airplane,” the FBI chief announced. All the State Department officials turned their heads to Armitage, who was running the building in Powell’s absence. “Let’s increase security outside the building,” Armitage said calmly, seeming unperturbed. Another aide piped up. “We probably need to think about getting the hell out of here,” he said. Armitage decided to evacuate, and an alternate command center was set up at the Foreign Service Institute in Arlington, Va. Senior State Department aides jumped in staff cars to race to Arlington but immediately ran into clogged traffic in Washington.

By Tuesday afternoon, the spooks were making progress. Eavesdroppers at the supersecret National Security Agency had picked up at least two electronic intercepts indicating the terrorists had ties to bin Laden. By nightfall, less than 12 hours after the attacks, U.S. officials told TIME that their sense that he was involved had got closer to what one senior official said was 90%. The next morning, U.S. officials told TIME they have evidence that each of the four terrorist teams had a certified pilot with them; some of these pilots had flown for an airline in Saudi Arabia and received pilot training in the U.S. It’s not yet clear whether the pilots were trained in the U.S., or in Saudi Arabia or both. Intelligence officials believe each team had four to six persons. Some team members, it is thought, crossed the Canadian border to get into the U.S. Sources told TIME that within the past few months, the FBI added to the U.S. watch list two men whom the bureau believed to be associated with one of the Islamic Jihad terror groups. Through a screwup, the suspects were lost. The two men appear to have been on the American Airlines Flight 77, the plane that crashed into the Pentagon, sources told TIME. Boston appears to have been a central hub for the operation; U.S. intelligence believes a bin Laden cell in Florida was a support group helping with the aviation aspects of the attack.

Intelligence officials poring over old reports believe they got their first inkling of planning for the attack last June, although at the time the intelligence was too vague to indicate the scale of the operation. In the summer U.S. embassies, particularly those in the Middle East, were put on heightened alert, as was the U.S. military in the region. The CIA was getting vague reports “of some kind of spectacular happenings” by terrorists, said a U.S. intelligence official, but the reports were vague as to timing. “A lot of this reporting we had in the summer that gained our attention and had us concerned, but wasn’t specific, could have been tied to this,” said a U.S. intelligence official.

Even had they known more, could officials ever have contemplated the scale of this thing? The blasts were so powerful that counterterrorism teams have begun asking the airlines for fuel loads on the plane; aviation experts have been asked to calculate the explosive yield of each blast — in kiloton terms. The reason? Washington wants to see if the planes amounted to weapons of mass destruction. “What we want people to realize is they’ve crossed a line here,” said a U.S. intelligence official. In fact, some senior Administration officials are considering drafting a declaration of war, although the State Department is leery since nobody knows precisely who the war would be against.

By contrast, as the day unfolded, it looked awfully easy to declare war on us. The attack was the perfect mockery of the President’s faith in missile defense: What if the missile is an American Airlines plane, and the pilot wants to kill you? It was only eight years ago that a group of zealots led by Ramzi Yousef tried to take the towers down from the bottom, with a rented Ryder truck full of homemade explosives. Their goal, as an unsigned statement presented later at trial put it, was no less than toppling “the towers that constitute the pillars of their civilization.”

U.S. officials learned a great deal from that attempt, notes retired ATF investigator Baughn. But the terrorists also learned. “They learned that they had to come at it from a different attitude,” Baughn says. “What they’ve done today was the easiest thing they could do. They didn’t have to bring in any explosives. They didn’t have to put a group of people together. They didn’t have to go find a safe house. They didn’t have to go construct anything. They didn’t have to rent a truck. They didn’t have to load the truck. They didn’t have to drive it to some place. All they had to do was hijack an airplane.” They made it look so easy, you wondered if the only reason the U.S. has not seen a hijacking in 20 years was because hardly anyone was trying. It’s a wonder why not; the Microsoft flight simulator and Fly! II — the two most popular simulators for personal computers — allow you to pretend to fly between the World Trade Center towers, and into them. Anyone looking to practice can buy the software off the shelf.

At 7:30 P.M. Tuesday, with the Pentagon still in flames, the congressional leadership, with a crowd of Senators and Congressmen behind them, stood on the Capitol steps. “When Americans suffer and when people perpetrate acts against this country, we as a Congress and as a government stand united, and stand together,” said an angry Dennis Hastert, Speaker of the House, with Democrat Dick Gephardt standing stony silent beside him. Both parties “will stand shoulder to shoulder to fight this evil,” Hastert promised. He asked everyone to bow their heads in a moment of silence. Afterward the Congressmen and Senators, Republicans hugging Democrats, broke out into a chorus of God Bless America.

As patriotism swelled, the day threatened to loop us into the kinds of barbaric blood feuds from which we’ve always been able to stay away. So people lashed out, getting angry at our not very humble foreign policy, complaining about a culture of ironic detachment that made us unmoved by a threat that was very real. (Though in the immediate aftermath of the attacks, pollsters found that by a huge proportion, 80%, Americans were ready to go to war, and prepared for the body bags that go with it.)

Whatever the outcome, it was clear that some things had changed forever. The attacks will become a defining reference point for our culture and imagination, a question of before and after, safe and scarred. By 10:30 Tuesday morning, four tourists from the Czech Republic were at the Empire State building, buying up all the postcards with pictures of the World Trade Center on them. “Soon there will be no more of these cards also,” one explained.

When one world ended at 8:45 on Tuesday morning, another was born, one we always trust in but never see, in which normal people become fierce heroes and everyone takes a test for which they haven’t studied. As President Bush said in his speech to the nation, we are left with both a terrible sadness and a quiet unyielding anger. He was wrong, though, to talk of the steel of our resolve. Steel, we now know, bends and melts; we need to be made of something stronger than that now — not excluding an unseasoned President new to his job.

Do we now panic, or will we be brave? Once the dump trucks and bulldozers have cleared away the rubble and a thousand funeral Masses have been said, once the streets are swept clean of ash and glass and the stores and monuments and airports reopen, once we have begun to explain this to our children and to ourselves, what will we do? What else but build new cathedrals, and if they are bombed, build some more. Because the faith is in the act of building, not the building itself, and no amount of terror can keep us from scraping the sky.

— Reported by the staff of TIME magazine

This article appears in the Sept. 14, 2001 issue of TIME.

One World Trade Center

One World Trade Center soars a symbolic 1,776 ft. (541 m) tall, higher than any other building in the country. Designed by architect David Childs of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill LLP (SOM), the office tower houses companies including Conde Nast, as well as the three-level One World Observatory at its peak, which began welcoming visitors earlier this year.

2 World Trade Center

The fate of 2 World Trade Center remained uncertain until this year, when 21st Century Fox and News Corp. signed on as the anchor tenants and a new terraced design by Bjarke Ingels was unveiled. The tower will rise 1,270 ft. (387 m), the second tallest of the new World Trade Center buildings, when it opens in 2020. Its construction site is shown at the bottom left of the above image.

3 World Trade Center

The next tower to open at the site will be 3 World Trade Center, which is slated for completion in 2018. Designed by Richard Rogers of Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners, the 1,079-ft. (329 m) skyscraper, shown at center in the above photo, has risen to about half its final height. When it opens, it will house offices for companies including GroupM, a media advertising firm, along with 150,000 sq. ft. (13,935 sq. m) of retail space.

4 World Trade Center

This 72-story skyscraper, designed by Fumihiko Maki of Maki and Associates, opened in 2013. Tenants include the City of New York and the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, the government agency that owns the World Trade Center site.

7 World Trade Center

The first new office building to rise at Ground Zero after 9/11 was 7 World Trade Center, which opened in 2006. Though it is now dwarfed by its taller new neighbors, the 52-story tower still stands out for its public art installations, including pieces by Jenny Holzer and Jeff Koons.

9/11 Memorial & Museum

In the space where the Twin Towers once stood, waterfalls now rush into two enormous square memorial pools. The pools are ringed with bronze panels inscribed with the names of all the 9/11 victims, as well as those who were killed in the 1993 World Trade Center bombing. Beneath the tree-shaded memorial plaza is an underground museum with multimedia exhibits that tell the story of 9/11 and its aftermath.

World Trade Center Transportation Hub

The new World Trade Center Transportation Hub was designed by architect Santiago Calatrava, whose plans were inspired by the image of a child releasing a white-winged bird. The nearly $4 billion station’s cavernous main hall is framed by two sets of white steel ribs that recall wings, and its roof features a skylight that is intended to retract for 102 minutes each year on the 9/11 anniversary, marking the duration of the attacks. The station, which will connect commuter rail lines to subways and ferries, has already begun opening to the public.

Performing Arts Center

An oft-forgotten piece of the World Trade Center redevelopment is the long-promised Performing Arts Center, which was once slated to be designed by architect Frank Gehry. The project’s budget was recently slashed and Gehry is no longer involved, but officials still say they are optimistic that a scaled-back version of the arts center will rise—eventually. The site for the Performing Arts Center is between the Transportation Hub, shown above, and One World Trade Center.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com