Two British human rights workers went missing while researching the mistreatment of migrant workers in Qatar, colleagues of the missing workers said Friday.

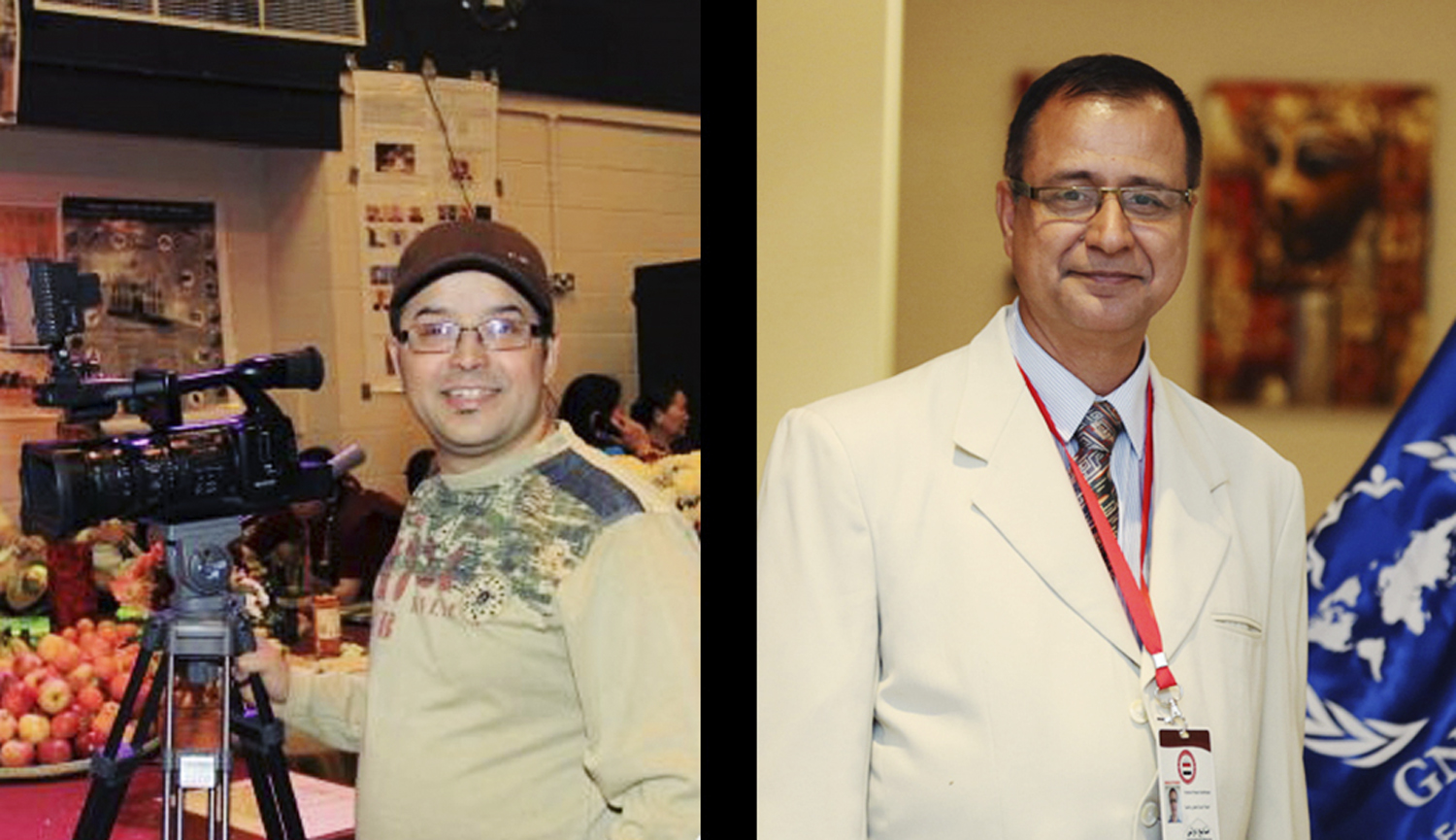

Krishna Upadhyaya, 52, and Ghimire Gundev, 36, had been in Qatar since Aug. 27 working on a report for the Norwegian-based Global Network for Rights and Development (GNRD) before “vanishing” five days ago, according to the organization. On Friday afternoon, a small group of human rights advocates delivered an angry letter to the ambassador of Qatar in the United Kingdom demanding “that the government of Qatar discloses what it is doing to find the two workers and ensure their safety.”

Neither the U.S. State Department nor the British Foreign Office have released any information about the situation. The Gulf state is slated to host the World Cup in 2022.

The sudden disappearance of the two men underscores growing tensions in the small, gas-rich nation, the wealthiest in the world per capita, which has drawn withering criticism in recent months for its treatment of roughly 1.5 million foreign workers, many of whom are employed in construction projects related to the World Cup.

International human rights groups and newspaper investigations have accused Qatar of fostering “slave-like” conditions, stripping visiting workers of basic rights, and allowing companies to pay them as little as 85 cents a day. Other reports indicate that workers live in cramped, unsanitary and unsafe conditions, and are forced to labor without basic protections, like adequate water and shade, in sweltering and dangerous environments.

Critics have also pointed at Qatar’s flawed immigration system, which makes it possible for employers to effectively hold migrants workers ransom by refusing to allow them to obtain exit visas. That issue rocketed into headlines last fall after professional soccer player Zahir Belounis said he was “stranded” in the country and appealed for international help to return to his home in France.

According to the Qatari government, roughly 1,000 foreign workers died in Qatar in 2012 and 2013, but human rights groups say that number is low. An ESPN investigation estimated that, even by conservative estimates, at least 4,000 migrant workers will die while working in Qatar by the opening ceremony of the World Cup.

In a large part due to such international attention, the Qatari government announced in May that it would take steps to better protect migrant workers’ rights, but human rights activists say they have yet to see any significant improvements. Sepp Blatter, the president of football’s world governing body, FIFA, has said that migrant workers’ conditions in Qatar are “unacceptable,” but has stopped short of calling to move the 2022 tournament.

The debate over migrant workers’ rights comes just months after FIFA launched an investigation into allegations that a Qatari official paid more than $5 million to secure his country’s successful bid to host the tournament. Dozens of advocates have since called for a new vote on which country should host the 2022 event.

GNRD said it suspects that Upadhyaya and Gundev, who are of Nepali heritage, were detained—the letter delivered Friday to the ambassador points the finger at Qatari police—but Qatari authorities have said nothing about the men’s whereabouts.

Upadhyaya, a researcher, and Gundev, a photographer, sent text messages to colleagues Sunday saying that they believed they were under surveillance and being followed by plain clothes police officers. They were filming interviews with migrant workers before they went missing.

Qatar, which is about the size of Connecticut and has fewer citizens than Cincinnati, has been at the center of mounting tensions in the Middle East. Its vociferous support for the Muslim Brotherhood has put it at odds with its neighbors in the Gulf and led Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, and the United Arab Emirates to withdrew their ambassadors from Doha this year in protest.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Haley Sweetland Edwards at haley.edwards@time.com