When Mao Zedong’s communists took power in China in 1949, their victory was supposed to herald a Marxist proletariat revolution that would create a workers’ paradise. Or at least that’s what the toiling masses were told. Reality proved somewhat different. Workers became cogs in Mao’s soulless industrial machine, controlled by the state and trapped in grinding poverty. After the advent of free-market reforms in the 1980s, millions slaved away in dank factories for meager wages, while the country’s communist cadres protected the foreign capitalists who exploited them. Those few workers brave enough to resist were beaten into submission—sometimes literally.

But over the past few years, Chinese workers have been fighting back. At the Power-One electric-adapter factory in Shenzhen one recent Monday afternoon, dozens of workers idly languish along the compound’s roadways, fanning themselves in the stifling summer heat. The assembly lines (then in the process of being sold by Swiss engineering company ABB to U.S. firm Bel Fuse) have already been silenced for a week. safeguard legal rights reads one banner hung overhead; we will never resume work if any one of us is fired another promises. Scores gather to complain loudly to Time about the poor treatment they’ve suffered. The local managers, they claim, haven’t been properly compensating them for overtime or paying all the required fees for their government health insurance and pensions. A policeman records them with a video camera, but they barely take notice.

The workers had tried less drastic measures to resolve their problems, but fed up with stalled negotiations, they handed their managers a final list of demands in June. When it was rejected, the factory’s 1,000 employees laid down their tools, vowing not to pick them up again until satisfied. Going on strike, says warehouse staffer Zeng Quan, 45, “is the only way we can protect our rights.”

Zeng and his comrades are participants in a true workers’ revolution taking place in China today. The country’s vast industrial zones have become hotbeds of protest as once cowed laborers demand—and often win—better benefits and working conditions on an unprecedented scale. China Labour Bulletin, a workers’ advocacy organization based in Hong Kong, counts as many as 60 to 70 strikes in China each month, roughly triple the number in 2011. Frustrated by decades of mistreatment, yet emboldened by their newly discovered influence, the workers of China have realized that the only way to grasp the Chinese dream is to take it for themselves. “They have no other way to go but to fight for their rights,” says Francine Chan, a labor advocate at the Hong Kong–based NGO Worker Empowerment.

A New Equation

The fallout could ripple far beyond China’s borders. Chinese workers churn out many of the products that we use every day—from iPads to blue jeans to baby toys—so what happens on China’s factory floors touches everyone. The transformation of China into the low-cost workshop of the world over the past three decades has been a key reason why prices for many consumer goods have remained so affordable. But as Chinese workers agitate for fatter salaries, better benefits and safer factories, they are adding to rising manufacturing costs. That could push up prices of many Chinese-made products at your local store and increase inflationary pressures throughout the developed world.

Yet China’s striking workers offer some good news for the world economy too. Better-paid Chinese will become bigger customers of everything from GM sedans to McDonald’s french fries, creating a new source of global growth and potentially healthier profits for U.S. companies. Greater rights for workers “is part of moving to a more mature economy,” says Frederic Neumann, co-head of Asian economic research at HSBC. “That’s ultimately in the interests of the world economy.”

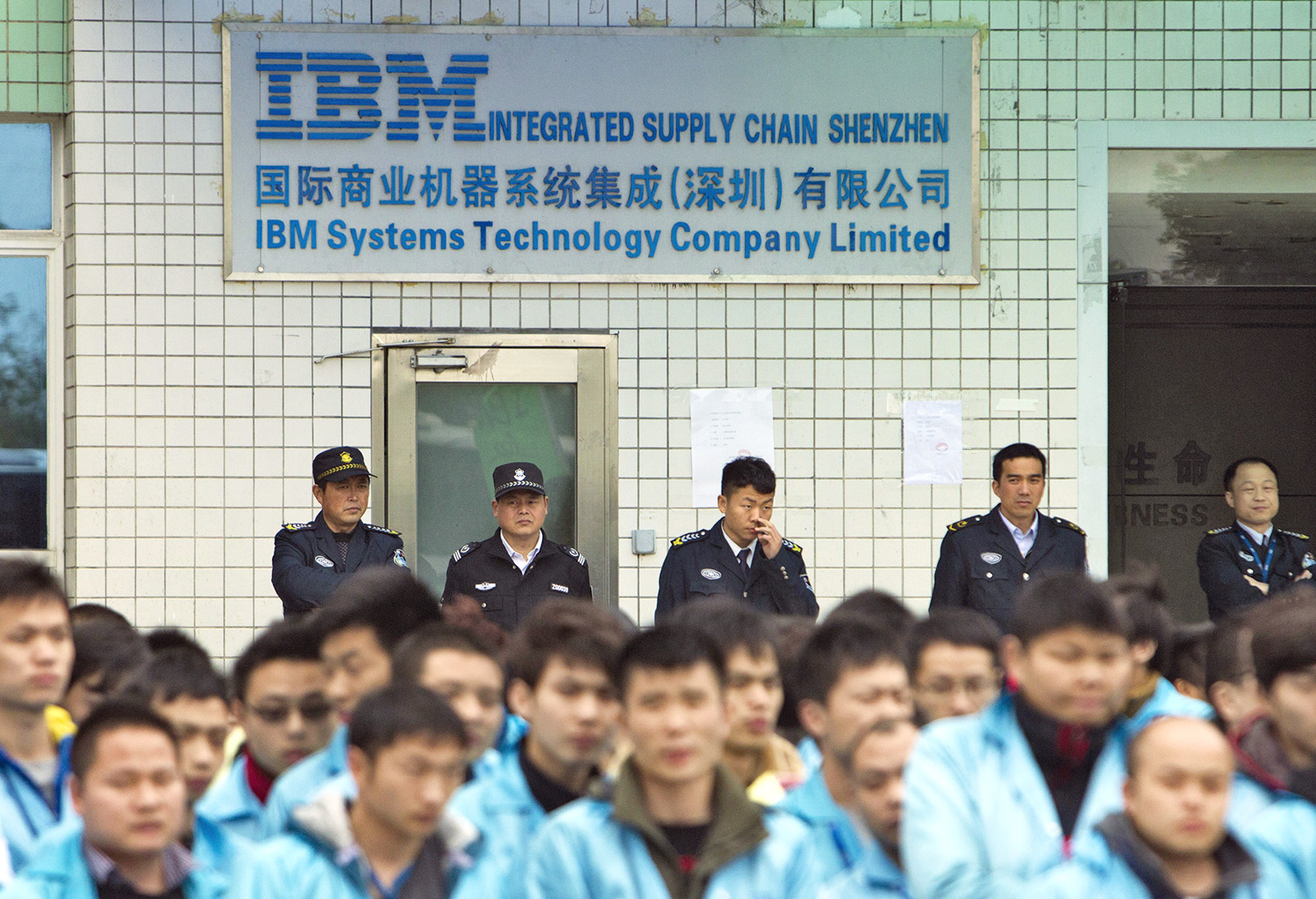

China’s newly assertive workers are rewriting the rules of doing business in the country. For most of the past 30 years, multinationals could open factories and outsource production without worrying too much that Chinese workers would disrupt their operations or contest their decisions. That’s no longer the case. In March, after retailing giant Walmart announced it was closing a store in the city of Changde, many of its employees demanded higher severance and blockaded the outlet. The dispute went into arbitration, and most of the disgruntled workers eventually accepted a larger settlement, according to Walmart. However, the union leader and a handful of holdouts are suing the retailer in court, says a lawyer representing the workers. (Walmart said in a statement that the company “acted in accordance with all applicable labor laws” when closing the store.) Also in March, workers at an IBM factory in Shenzhen staged a strike over their transfer to Chinese PC maker Lenovo, which will acquire the plant as part of its purchase of the U.S. technology company’s low-end server business.

The rising labor activism is also a threat to the stability of global supply chains that reach into China. In April, thousands of workers walked off the job at a shoe factory in the southern city of Dongguan owned by Yue Yuen Industrial, a supplier for global brands like Nike and New Balance. Production was so badly disrupted that Adidas was forced to temporarily shift some orders to other suppliers. Yue Yuen agreed to pay extra monthly living allowances and full social-insurance fees to persuade its employees to return to work. The Power-One staffers in Shenzhen prevailed as well. After the factory was shut for nearly two weeks, the company compromised and agreed to give annual bonuses, offer more-secure contracts and pay all outstanding insurance charges, according to the workers. (ABB and Bel Fuse had no comment on the strike or its resolution.) Chinese strikers “know they can be successful,” says Geoffrey Crothall, communications director at China Labour Bulletin. “They are in a better bargaining position than they ever were.”

That’s thanks to rapid change in the Chinese economy. During the 1980s and ’90s, labor was plentiful as tens of millions from the impoverished countryside regularly streamed into the country’s new industrial parks in search of jobs—any jobs—that could lift their incomes. Employers, inundated with applicants, could staff their assembly lines for a pittance. But in recent years that flood has turned to a trickle. The workforce has been shrinking since 2012, due in part to the government’s more than three-decade-old one-child policy. As the Chinese economy keeps growing, workers can now find ample opportunities at home, instead of taking grueling jobs in coastal factories far from their families and friends. Also, because of the Internet, young Chinese are better informed about labor laws, contracts and benefits than earlier generations of workers. All of these factors are helping to push up wages in China—by nearly 14% in the private sector last year alone.

Today’s workers are asking for more from their bosses than their parents did. Ye Feng, 26, ventured to Dongguan hoping not just for higher pay but also improved working conditions. In his previous job at a plastics factory in a nearby town, he worried that the chemicals and intense heat from the machinery were ruining his health, so now he’s judging his potential employers based on the cleanliness and safety of their factories. “I’ll look around to see what meets my expectations,” Ye says. Liu Ye, a 30-year-old veteran of electronics factories, prefers a company that covers her room and board, won’t assign her to a night shift and pays at least $500 a month—a pretty good salary for factory work in the town, where the minimum wage is about $210. “The dormitory must have air-conditioning,” she says. Zhang Qinlong intends to avoid tedious assembly lines altogether. The 26-year-old had been a technician in a textile factory, but now he desires a managerial post or a job where he can pick up some engineering skills. “I’m paying much more attention to the prospects of the job,” Zhang says. “This way I can earn more money in the future.”

Factory managers have no choice but to accommodate these newly empowered Chinese workers. Dapu Telecom, which produces components for mobile-phone systems, has had to introduce all sorts of special privileges over the past two years to attract workers to its Dongguan factory. Dapu rents larger, more comfortable dormitories to house the staff, pays for birthday parties and regular outings to movies and karaoke parlors and even funds annual vacations for the workers. Such perks are expensive—Dapu spends 50% more on each employee today than only five years ago, says operations director Chen Zili. But if Dapu didn’t pay up, workers would just find jobs elsewhere. “The workers know how to bargain, how to protect their interests,” Chen says. “The balance of power has changed.”

Risky Business

Not entirely, though. workers who stand up for themselves say they still face harassment by company officials and local police, and can lose their jobs—or even worse. Take the case of Zhang Chengyan, 30, an employee at the Shenzhen branch of Chinese state-owned logistics company Sinotrans. Zhang was chosen by his fellow workers to represent them in a dispute with management over its decision to relocate the Shenzhen operation to next-door Dongguan. Many of the workers opposed the move because they were unwilling to uproot themselves from their Shenzhen homes and worried the relocation would result in poorer pay and working conditions. When the employees asked Sinotrans for compensation for those who refused the transfer, however, they were told none was on offer. The staff had only two choices, the managers informed them: relocate or resign.

The workers tried negotiating with Sinotrans, but in late May matters took an ugly turn. Zhang says he and six other worker representatives were summoned by Sinotrans to a hotel for negotiations—or so they thought. Once they were inside a meeting room, says Zhang, 20 men whom he describes as “thugs” rushed in, pinned them to the floor or against the walls and took their company IDs. Then a man Zhang says he recognized as a Sinotrans manager told them to stop organizing the workers—if they persisted, he told them, their lives would be in danger. (Time has repeatedly requested comment from Sinotrans, but after contacting two departments at its Beijing headquarters, officials there said they had no information on the situation in Shenzhen.) As news of the alleged intimidation spread, Zhang’s fellow workers became furious, with most of them defiantly going on strike. Zhang, too, remains undeterred. He and his colleagues are taking Sinotrans to court. “What happened is very unfair,” he says.

Activists like Zhang are vulnerable to abuse because they’re on shaky legal ground. While unions exist in China, they are under the umbrella of the state-managed All-China Federation of Trade Unions, which despite its name has historically shown little interest in defending its members. Independent efforts to unionize are prohibited, and labor activists are often targeted by the government. Wu Guijun, whom authorities in Shenzhen suspected of organizing a demonstration at a furniture factory in 2013, was detained for one year for “gathering a crowd and disrupting public order,” though the charges against him were later dropped. Ironically, the Communist Party—supposedly the champion of the proletariat—is afraid that China’s proletariat could become a political threat, much as Lech Walesa’s Solidarity movement did in 1980s Poland. “The government is worried that if the workers have their own unions, then what happened in Poland will happen in China, that they would be powerful enough to overthrow the Communist Party,” says Shenzhen-based labor-law expert He Yuancheng.

While apparently more tolerant of strikes, officials will still occasionally harass those individuals who seem to be their organizers. The Power-One factory workers in Shenzhen, for instance, avoided naming formal representatives, fearing they could be targeted by the authorities. And in recent weeks, labor activists say the government mood toward labor has soured, with officials stepping up pressure on the workers to curtail their protests—probably part of a greater effort by Beijing to crack down on all forms of dissent.

Yet, with decades of unresolved grievances, and no trustworthy process to resolve them, China’s workers will likely resort to strikes in greater numbers—however the Communist Party responds. Workers of China are uniting, and the promise of revolution—a real revolution—may finally be within their reach. —with reporting by Haze Fan / Shenzhen

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com