You are getting a free preview of a TIME Magazine article from our archive. Many of our articles are reserved for subscribers only. Want access to more subscriber-only content? Click here.

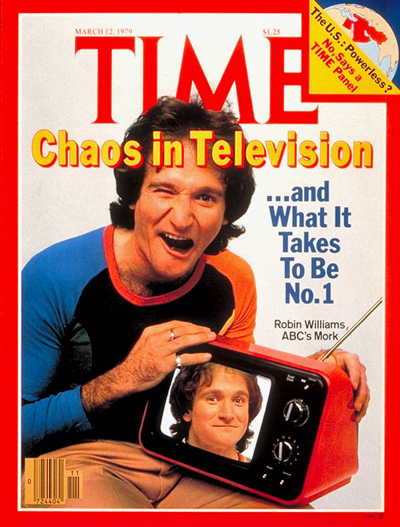

Five months ago he was what Hollywood likes to call a complete nobody. A struggling comic, he had passed virtually unnoticed through improvisational clubs and two flop TV series (the revived Laugh-In, the Richard Pryor Show). Then, last fall, ABC unveiled its new offerings for the 1978-79 season. Robin Williams, 26, was given the lead in Mork & Mindy, a spacy sitcom, and he became what the moguls love to call an overnight star. For once the Hollywood hyperbole is actually appropriate; Mork & Mindy is often at the top of the charts and is seen by an average of 60 million viewers each week. To be the star of TV’s No. 1 hit is to be the most highly visible show-biz personality in the country.

Mork & Mindy seems an unlikely bet for such exaltation: the program is fundamentally a retread of such tired sitcoms as My Favorite Martian and Bewitched. It tells the story of Mork (Williams), an alien eggplanted, so to speak, from the planet Ork, who settles in Boulder, Colo., with a winsome ingenue, Mindy (Pam Dawber). The secret of the program’s runaway success is Williams. He is not only an inspired clown but also a perfect entertainer for TV’s mass audience. Mork has the innocence and enthusiasm of a toddler discovering the world. But he is one toddler who can talk. Artless, gullible, endearing, he lets the audience in on every transparent thought that whirls through his head. His rambling is wildly unpredictable, in part because Mork talks not only to himself but to three or four parts of himself—and they talk back.

Children love him because his daffy repertoire of Ork language can be mimicked endlessly. Already Mork’s “nano, nano” (translation: hello) has replaced the Fonz’s “aaaayyy” as the catchword of the nation’s kids. Adults like his spontaneous riffs. On one program he launched into a singsong: “Shah, Shah, Ayatollah [I tol’ yuh], Shah, Shah, Ayatollah so.”

People on Ork do not have emotions. Though he can be possessive about Mindy, sex is a mystery to Mork (he did once get a crush on a department store dummy). “He has the cootchycoo quality,” says a casting director at NBC.”You want to go up to him and pinch his cheeks.”

It could be argued that Williams landed in the right role in the right time slot (8 p.m., when children control the nation’s sets). But Williams is not so much lucky as talented. In his stand-up nightclub act, which he does for free, to keep in touch with live audiences and to try out new material, he displays a range that encompasses Jonathan Winters, Danny Kaye, Steve Martin and Daffy Duck. Though always wearing the same costume—baggy pants, loud shirts, suspenders—he whips in and out of a multitude of comic characterizations. He can mimic the cadences of Shakespeare, many foreign languages, an ark of animals, various machines. His act includes a redneck used-car salesman, a Russian comic, a gay director, a touchingly mad grandpa.

The man behind this comic madness is the product of a comfortable but solitary upbringing. The last child of a Ford Motor Co. vice president, Williams grew up in Chicago, the Detroit suburbs and Tiburon, near San Francisco. When left alone, he summoned up his own world, maneuvering his toy soldiers and cloning his own versions of wacky Jonathan Winters characterizations like Maude Frickert. After two stabs at college in California, he moved to New York City to study acting. For spending money, he and a partner did white-faced comedy mime in front of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, occasionally matching acts with Acrobat Philippe Petit, who went on to walk between the towers of New York’s World Trade Center. On a boffo day, Williams made $75.

Eventually Williams returned to San Francisco, where he hung around the city’s small comedy clubs. While tending bar, he met a dancer named Valerie Valardi, whom he married last June. Valerie urged him to try the clubs in Los Angeles; she helped catalogue his material and shape his act. Once Williams had played Los Angeles’ Comedy Store and Improvisation, he began to get TV work.

Mork appeared first when Robin played him in a one-shot appearance on Happy Days. The mail response to the episode was so large that a spin-off series was created for Williams. Mork & Mindy was a hit even before it went on the air. Director Howard Storm recalls the series’ first taping: “Most of the time the studio audience for a new show is down. They don’t know the characters. With Mork, they went crazy.”

Now that he is famous, Williams tries to live in the same casual way. He and Valerie still like to practice yoga, play backgammon and chess, ski, surf and drive around Los Angeles for the fun of it. Privacy, however, is becoming increasingly elusive. The other day he was roller-skating in Venice, a funky, fashionable section of the city, where people like to walk around on wheels. He coasted into a phone booth to make a call, but was quickly surrounded by fans peeking through the glass. Said he: “I felt like I was in the San Diego Zoo.”

Williams finds TV’s ratings struggle frightening. This season he became fascinated by a short-lived NBC sitcom, Who’s Watching the Kids?, that was shot on a lot near Mork. “I saw its birth and death,” he says wistfully. “I watched people fight for it. It is strange for me to know that I’m being used to cut the guts out of other new series.” He chuckles at the talk that Mork & Mindy may soon have its own spinoff. “What would they spin off? It would be more like a skin graft.”

Williams has an inhibiting five-year contract to play Mork, but he is moving beyond television. A comedy album is on the way, and next January he will star in the movie Popeye. Williams hopes that five seasons of Mork will not be too much. Says he: “If you find yourself stiffening up and not taking chances, then you become a situation comedy comedian.”

What will not suffer is his bank account. Already Williams makes $15,000 per episode, and that figure may soon be renegotiated upward. He and Valerie have bought an eight-room house in Topanga Canyon. Williams has not, however, joined the smart crowd in Hollywood by acquiring a Mercedes or a Rolls; he has bought a battered 1966 Land Rover. Says he: “I can’t deal with new cars. I like a car that’s like me —you never know what’s going to happen next.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com