A new survey finds that 60% of incoming college football players support unions for college athletes. The horror! Were such unions allowed, our glorious cities would crumble to nothing more than shoddy tents stitched together from tattered remnants of Old Glory; our government officials would be loincloth-clad elders gathered in the rubble of an old McDonald’s passing a talking stick; our naked children would roam the urban wilderness like howling wolves, their minds as blank as their lost Internet connection. We would be without hope, dreams or a future.

Or at least that’s what you might believe based on the nuclear reaction a few months ago when a dapper man named Ramogi Huma attempted to destroy everything that America holds sacred with just such a proposal to unionize college athletes. His argument was simple: that college athletes should be classified as employees of their colleges and therefore receive certain basic benefits. He did not advocate player salaries but only programs to minimize brain-trauma risks among athletes, a raise in scholarship amounts, more financial assistance for sports-related injuries, an increase in graduation rates and several other similar goals.

You would have thought he’d proposed dressing the Statue of Liberty in a star-spangled thong.

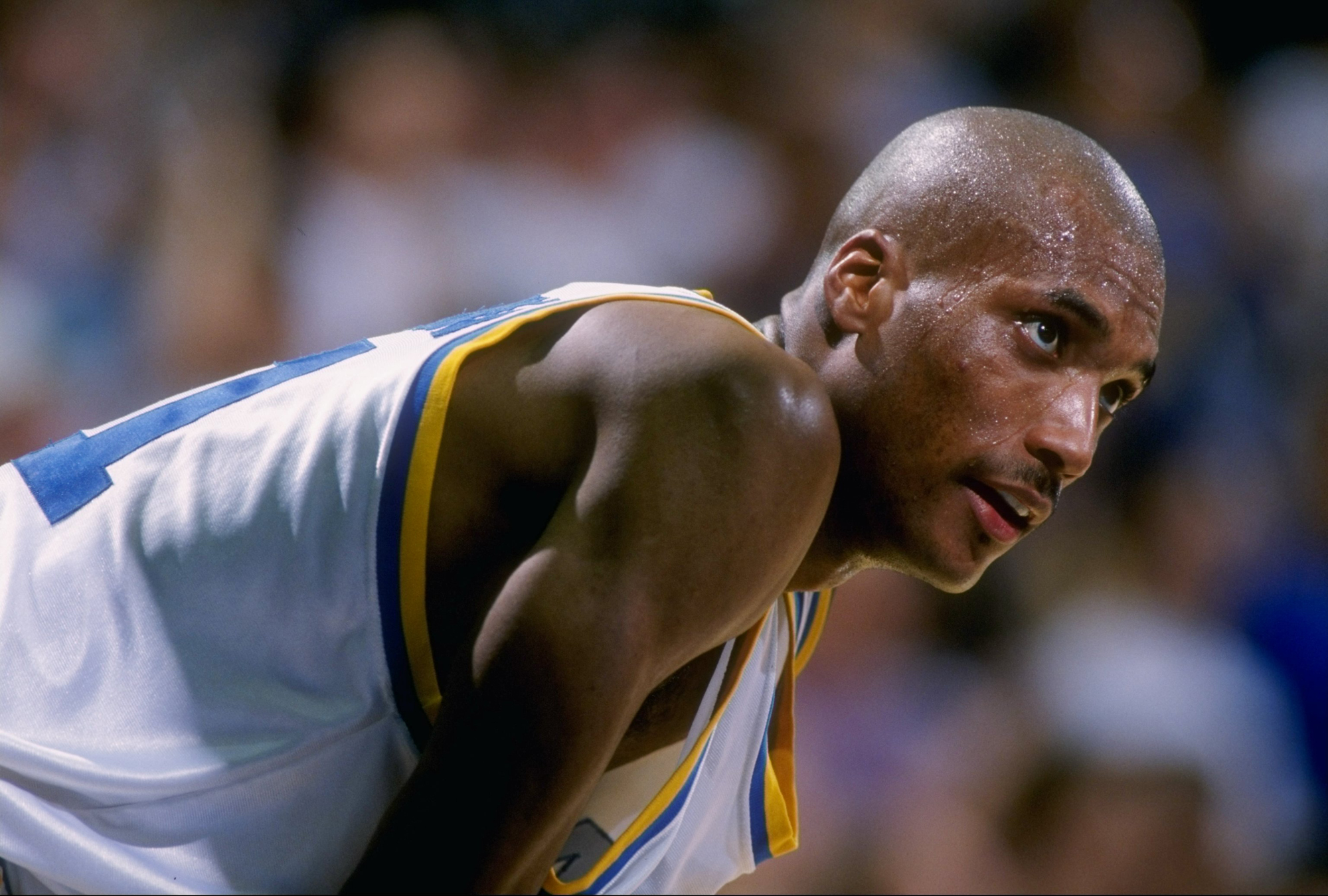

But Huma is not alone in his assault on the NCAA’s ironfisted control of all things related to college athletics that might generate income (as befits its new motto: “If it earns, it’s ours”). Other current and former college athletes are questioning the NCAA-brand Kool-Aid. Former UCLA basketball player Ed O’Bannon, along with a few other players, is suing for players to have control over the use of their likenesses, which earn millions of dollars for the NCAA — but not a cent for the players. Another class-action antitrust suit has been filed to remove the cap on players’ compensation — currently limited to the value of the scholarship they receive plus room and board — as an illegal restraint of trade.

Predictably, the NCAA is against any scheme to get college players paid, claiming that unionizing will “completely throw away a system that has helped literally millions of students over the past decade alone to attend college.” Attend but not necessarily complete, especially if you suffer any long-term injury. Because if you don’t compete, you don’t complete.

And the NCAA has the backing from some powerful Washington politicians who, according to Senator Lamar Alexander (R., Tenn.), worry about strikes that will “destroy intercollegiate athletics as we know it.” Speaker of the House John Boehner (R., Ohio) also chimed in: “I haven’t looked at the specifics of this and what would be required, but having formally chaired the House Education and Workforce Committee and worked with the National Labor Relations Act for the last 30 years, I find it a bit bizarre.”

Nothing more reassuring than someone who acknowledges he hasn’t really “looked at the specifics” but has an opinion anyway.

Well, Congressman, here are some specifics:

While these coaches and executives may deserve these amounts, they shouldn’t earn them while the 18-to-21-year-old kid who plays every game and risks a permanent career-ending injury gets only scholarship money — money that can be taken away if the player is injured and can’t contribute to the team anymore.

The irony is that the NCAA and other supporters claim paying athletes would sully the purity of college sports — desecrating our image of a youthful clash of school rivalries that always ends at the malt shop with school songs being sung and innocent flirting between boys in letterman jackets and girls with pert ponytails and chastity rings. In reality, what makes college sports such a powerful symbol in our culture is that it represents our attempt to impose fairness on an otherwise unfair world. Fair play, sportsmanship and good-natured rivalry are lofty goals to live by. By treating the athletes like indentured servants, we’re tarnishing that symbol and reducing college sports to just another exploitation of workers, no better than a sweatshop.

Everyone’s hope was that once these inequities were exposed, the NCAA would do the right thing. That hasn’t happened on a meaningful scale. Instead, it battles in court, issues press releases and appeals to Norman Rockwell nostalgia.

The athletes are left with the choice of crossing their fingers and hoping their fairy godmothers will persuade the NCAA to give up money that it doesn’t have to, or forming a collective bargaining group to negotiate from a place of unified strength.

Most Americans agree that the athletes are being shortchanged. A recent HuffPost/YouGov poll concluded that 51% of Americans believe that universities should be required to cover medical expenses for former players if those expenses were the result of playing for the school. A whopping 73% believe that athletic scholarships should not be withdrawn from students who are injured and are no longer able to play.

But when it comes to these same student-athletes’ forming a union, an HBO Real Sports and Marist College Center for Sports Communication poll showed 75% of Americans opposed to the formation of a college-athlete union, with only 22% for it.

Why such a difference between wanting equity and supporting the best means to achieve it? Despite 14.5 million Americans’ belonging to labor unions, we’ve always had a love-hate relationship with them.

The love: Unions can be like protective parents arguing with an arrogant teacher over their child’s unfair grade. The hate: Unions can be like bossy spouses who complain about all the work they do for you while shoveling corn chips into their maw on the La-Z-Boy.

Our relationship with college athletes is much clearer. We adore and revere them. They represent the fantasy of our children achieving success and being popular. Watching them play with such enthusiasm and energy for nothing more than school pride is the distillation of Hope for the Future.

But strip away the rose-colored glasses and we’re left with a subtle but insidious form of child abuse.

Which raises the question: How will things change?

When I was a young, handsome player at UCLA, with a full head of hair and a pocket full of nothing, I sometimes had a friend scalp my game tickets so I could have a little spending money. I couldn’t afford a car, which scholarship students in other disciplines could because they were permitted to have jobs, so I couldn’t go anywhere. I got bored just sitting around my dorm room and frustrated wandering around Westwood, passing shops in which I couldn’t afford to buy anything.

How will things change? It’s possible the NCAA will eventually capitulate to these commonsense requests, but since it hasn’t so far, the only reason it would change its mind now would be the threat of a union. Either way, the union will have caused positive change for these young athletes. But without a union, these student-athletes will be without any advocates and will always be at the whim of the NCAA and the colleges and universities that profit from them.

Abdul-Jabbar is a six-time NBA champion and league Most Valuable Player. Follow him on Twitter (@KAJ33) and Facebook (facebook.com/KAJ). He also writes a weekly column for the L.A. Register.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com