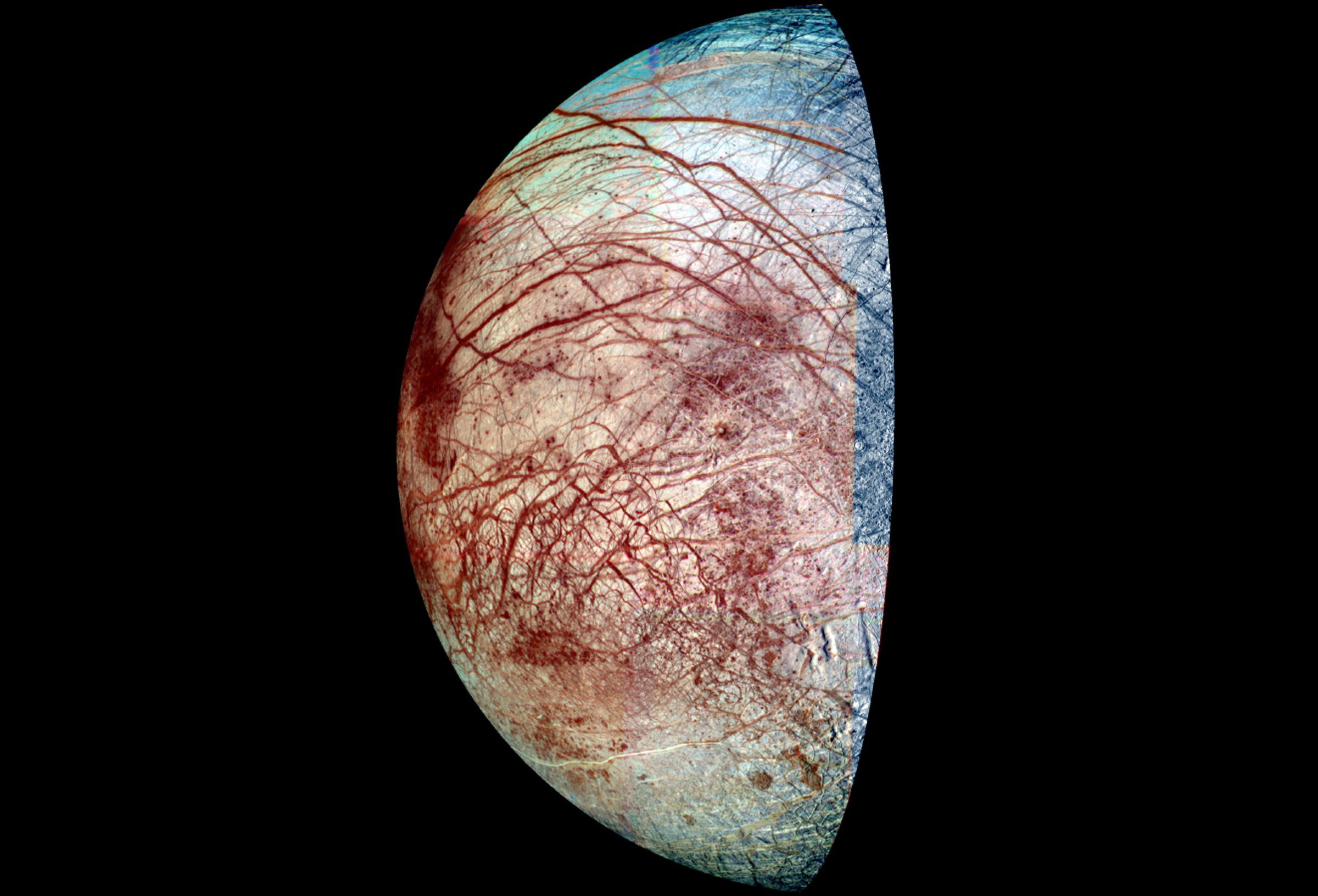

The odds that the universe is bursting with life seem to be getting better all the time. Astronomers recently announced that there could be an astonishing 20 billion Earthlike planets in the Milky Way—and that’s if you’re limiting the pool to planets orbiting stars like the Sun. If you add the small, reddish stars known as M-dwarfs, which also harbor planets, the number is even greater. Within our own Solar System, meanwhile, the evidence for a plausibly life-friendly ocean on Jupiter’s moon Europa is stronger than ever, and the Curiosity rover has confirmed that some kinds of bacteria could have thrived in Mars’s Gale Crater billions of years ago. On a more universal scale, scientists know for a fact that two of the essentials for life—water and carbon—can be found literally everywhere.

How abundant life actually is, however, hinges on one crucial factor: given the right conditions and the right raw materials, what is the mathematical likelihood that life will actually would arise? If it’s a 50-50 proposition, then given the vast amount of available real estate, biology would have to be popping up all over the place. But if it’s a one-in-a-trillion shot, we could indeed be all alone in the vastness of space. To date, despite more than a half-century of trying, nobody has managed to figure how life on Earth began. Without knowing the mechanism by which inanimate chemistry assembled and bestirred itself, admits Andrew Ellington, of the Center for Systems and Synthetic Biology at the University of Texas, Austin, “I can’t tell you what the probability is. It’s a chapter of the story that’s pretty much blank.”

Given that rather bleak-sounding assessment, it may be surprising to learn that Ellington is actually pretty upbeat. But that’s how he and two colleagues come across in a paper in the latest Science. The crucial step from nonliving stuff to a live cell is still a mystery, they acknowledge, but the number of pathways a mix of inanimate chemicals could have taken to reach the threshold of the living turns out to be many and varied. “It’s difficult to say exactly how things did occur,” says Ellington. “But there are many ways it could have occurred.

(MORE: Unknown Force Kicks Stars Out of Milky Way. Really.)

The first stab at answering the question came all the way back in the 1950s, when chemists Stanley Miller and Harold Urey passed an electrical spark through a beaker containing methane, ammonia, water vapor and hydrogen, thought at the time to represent Earth’s primordial atmosphere. When they looked inside, they found they’d created amino acids, the building blocks of proteins.

That experiment is now considered a dead end, since the atmosphere probably didn’t look like that after all, and also since the steps from amino acids to life turned out to be hellishly difficult to reproduce—so difficult that it’s never been done. But Ellington sees things differently. “It was a monster achievement,” he says, “and since then we’ve learned a truckload.”

Scientists have learned so much, in fact, that the number of places life might have begun has grown to include such disparate locations as the hydrothermal vents at the bottom of the ocean; beds of clay; the billowing clouds of gas emerging from volcanoes; and the spaces in between ice crystals.

(MORE: Why Dust is the Most Important Stuff in the Universe)

The number of ideas about how the key step from organic chemicals to living organisms might have been taken has multiplied as well: there’s the “RNA world hypothesis” and the “lipid world hypothesis” and the “iron-sulfur world hypothesis” and more, all of them dependent on a particular set of chemical circumstances and a particular set of dynamics and all highly speculative.

Worse, however things played out, all evidence of the process has long since vanished: the very first cells have left no traces, and the environments that nurtured them have disappeared as well. The best scientists can hope to do is to create a proto-cell in the lab.

“Maybe when they do,” says Ellington, “we’ll all do a face-plant because it turns out to be so obvious in retrospect.” But even if they succeed, it will only prove that a manufactured cell could represent the earliest life forms, not that it actually does. “It will be a story about what we think might have happened, but it will still be a story.”

The story Ellington and his colleagues have been able to tell already, however, is a reason for optimism. We still don’t know the odds that life will arise under the right conditions. But the underlying biochemistry is abundantly, ubiquitously available—and it would take an awfully perverse universe to take things so far only to shut them down at the last moment.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com