It’s been 30 years since the release of Stop Making Sense, the Jonathan Demme-directed Talking Heads concert pic that’s widely recognized as one of the greatest live music films of all time.

Stop Making Sense paired Demme — years before he won Best Director for Silence of the Lambs — with the band Talking Heads, just as the New York-based art rock group were becoming musical icons.

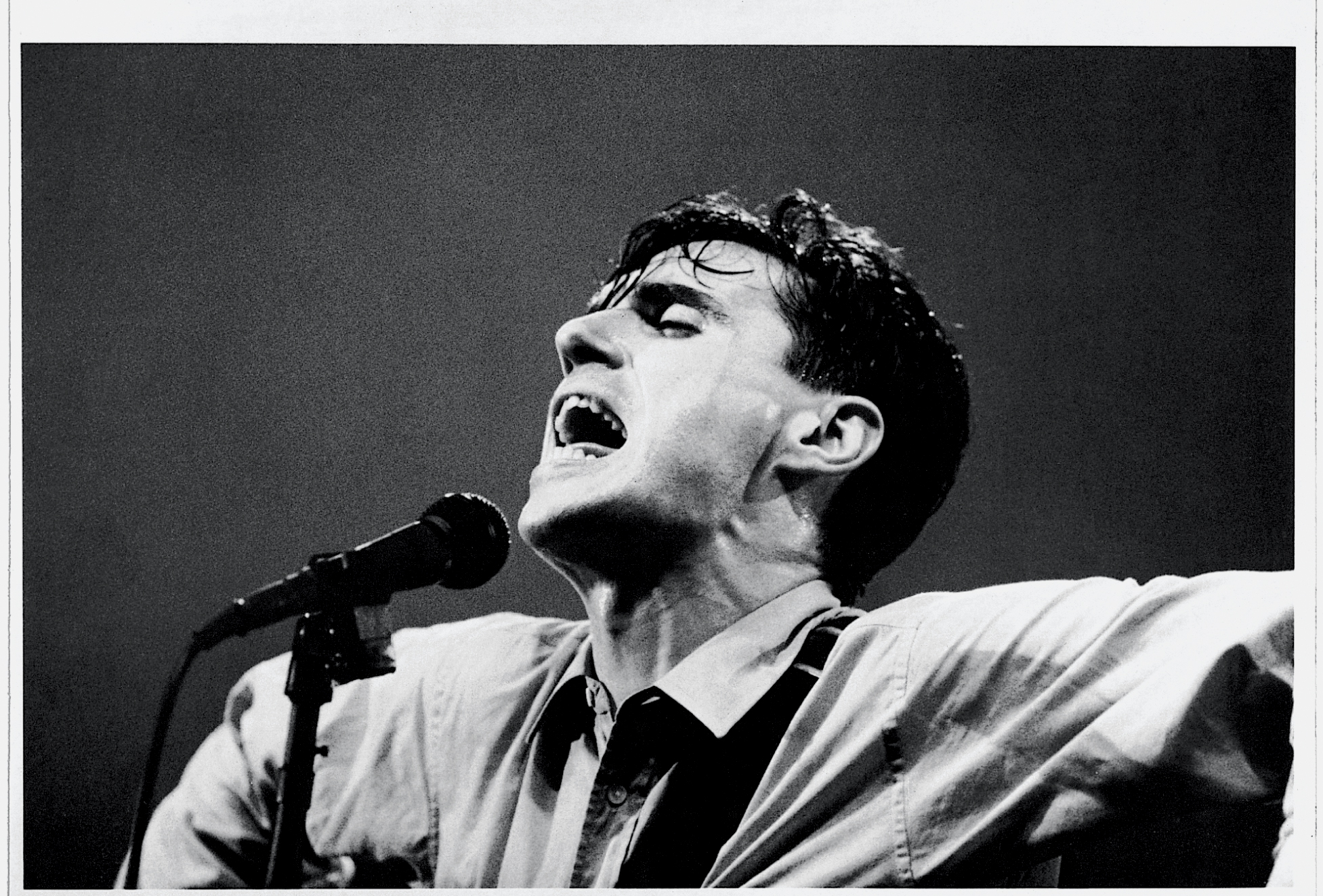

The film begins with the band’s frontman and impresario, David Byrne, walking on stage a boombox in hand. He sets it down, turns it on and starts to sing along with the Talking Heads’ song “Psycho Killer.” He is soon joined by bassist Tina Weymouth while stagehands build a drum platform for Chris Frantz. Backup singers and horn players appear and the show goes on, building into a frenzy while Byrne throws himself around the stage like a possessed version of Mick Jagger. That energy carries throughout the film, fusing Demme’s sweeping cinematographic style with Byrne’s eye for stagecraft and the art of the show.

To mark the occasion, the film is being made available digitally for the first time ever by Palm Pictures, along with a limited theatrical engagement this summer and fall. When asked why it took so long for a film that used some of the most modern equipment and techniques of its age — it was the first rock movie made using entirely digital audio techniques — to become available digitally, Demme shrugged: “I guess we just weren’t paying attention?”

TIME talked to both Demme and Byrne as they reflected on making Stop Making Sense and the lasting legacy of the film:

Demme: “In early 1983, Gary Goetzman and I went to see my favorite band, the Talking Heads, at the Hollywood Bowl in Los Angeles. The show was like seeing a movie just waiting to be filmed. We tracked David Byrne down and pitched him on the idea of teaming up to make the picture.”

Byrne: “I realized the show was ‘cinematic’ and that it sort of had a narrative arc. It might work on film, or so I believed.”

Demme: “David really saw this movie in his own head long before we came and pitched him on letting us shoot it.”

The two connected through a mutual friend, Nadia Ghaleb (according to Byrne), but they already shared a mutual appreciation of each others’ work.

Byrne: “I knew Jonathan’s work. I loved Melvin and Howard.”

Demme: “I was a Talking Heads fan from the very beginning.”

To make the film, the band turned to the parent company of their record label, Sire, for funding.

Byrne: “Our manager, the late Gary Kurfirst, went to Warner Records for a ‘loan.’ They got paid back and sold some live albums too.

With financing secured, the filming could begin.

Byrne: “Jonathan followed us on tour for about a week or so prior to filming, so he knew the show pretty well.”

Demme: “The big suit, the lighting, the staging, the choreography, the song line-up — everything was there in the show before the filmmakers showed up.”

The so-called big suit became one of the most iconic images of the show, the band and the film:

Demme: “It was all part of David Byrne’s original concept for the staged show, from the beginning.”

Byrne: “I was in Japan in between tours and I was checking out traditional Japanese theater — Kabuki, Noh, Bunraku — and I was wondering what to wear on our upcoming tour. A fashion designer friend (Jurgen Lehl) said in his typically droll manner, ‘Well David, everything is bigger on stage.’ He was referring to gestures and all that, but I applied the idea to a businessman’s suit.”

Filming took place over four nights at the Pantages Theater in Los Angeles, while the Talking Heads were on tour following the release of their album, Speaking in Tongues:

Demme: “Those four nights of filming were four of the most thrilling shoots of my life. Everything went flying by so fast it was just one ecstatic blur for me.”

Byrne: “During the shoot every day was spent re-balancing the lights so that the show would look to the camera as it did to the eye, as well as blocking out camera moves.”

Demme: “It was wonderful that our Director of Photography was the late/great Jordan Cronenweth, because Jordan was able to help David achieve on screen what was never completely possible with the lighting scheme in those big live arena shows, because there’s so much ambient light in those rooms that it blows out the starkness of true graphic black and white lighting design.”

Byrne had an attention to detail and an eye for design that was vast in scope:

Byrne: ”Edna Holt, one of the incredible singers (see 20 Feet from Stardom) changed her hair the day before we started shooting! I freaked out — hair whipping was a big part of the show —so I paid for her to get a weave immediately. It took her many, many hours, poor girl, but it worked.”

Stop Making Sense was a true collaboration between the two men, with each contributing their own aesthetic ideas about music, cinematography and stagecraft into a cohesive whole of avant-garde rock-and-roll theater. Both Demme and Byrne were eager to credit their collaboration and each other for the end result:

Demme: “Most of these dynamics arose from David Byrne’s original vision, but it was a highly collaborative experience.”

Byrne: “Jonathan saw things in the show that I didn’t realize where there or didn’t realize how important they were.”

Demme: “We shot it together, cut and mixed it together, and we all went running off to the festival circuit together as soon as we had our first print.”

Byrne: “[Demme] saw the interaction of the personalities on stage, how it was an ‘ensemble piece’ if it were viewed as one would a scripted film. He also realized that to suck the viewer into that ensemble, there would be no interviews and no shots of the audience until almost the very end.”

Demme: “In the cutting room we quickly discovered that there was always something far more interesting going on on stage than in the ‘best’ of our audience footage. This led to the realization that if we pulled back from showing the live audience, it made our film feel that much more specially created for our movie audience!”

The film also used a number of long camera shots to capture all the on-stage action in beautiful sweeping shots. It’s something Demme would replicate in future music documentaries like Storefront Hitchcock and Neil Young: Heart of Gold.

Demme: “The use of extended shots instead of quick cuts is a result of my belief that there is great power available by holding on any extended terrific moment and letting the viewer become more deeply involved in the performance at hand, instead of constantly interrupting the flow with un-needed cuts. Too much cutting usually speaks to a lack of editorial confidence in the players and the music.”

While Byrne tends to be the film’s focal point — and he is rarely off-camera throughout — the real star of the show is the music: the exuberant, funk-influenced rock that pushed the Talking Heads from the New York underground, where they opened for the Ramones at CBGB, to hitting the Billboard charts. The film captures their energy perfectly, building in tempo and attempting to force even the most reluctant audience members from their seats:

Byrne: “There were many screenings, film festivals and all that — many of which featured dancing in the aisles.”

Demme: “I adore film and I adore music. I often find myself feeling that filming music is somehow the purest form of filmmaking. This crazed collision of sound and images, the intense collaboration, these incredibly cinematic performances. And for the nights you’re filming, a non-player like me gets to feel somehow part of the band.”

Byrne: “I think the film and the show showed that a pop concert could be a kind of theater — not in the pretentious sense, but in the sense that it could be visually and even sort of dramatically sophisticated and yet you could still dance to it.”

Demme: “I knew that we had captured the magic of an extraordinary band at just the right moment, but didn’t imagine it would still be so around and feeling so fresh 30 years later. Makes sense now, though.”

Demme: “I love this film passionately with all my heart.”

You can purchase Stop Making Sense on iTunes here.

MORE: Love Story: A Q&A with Singer-Songwriter Robyn Hitchcock

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com