In my print TIME column this week (subscription required), I look at how American viewers are learning to read their TV shows–through the increasing use of subtitles in shows from The Americans (Russian) to The Returned (French) to NBC’s new Greg Poehler sitcom premiering tonight, Welcome to Sweden (um, guess). Until recent years–when, for instance, Lost included lengthy flashbacks in Korean–subtitles were assumed to be a dealbreaker for U.S. viewers. (If English was good enough for the Bible, dammit, it’s good enough for our shows!)

Being able to have characters speak in their native languages–or sign, as on Switched at Birth–opens possibilities for TV writers. It’s an avenue for character and conflict, even on an amiable fish-out-of-water show like Sweden. It forces viewers to focus on a show rather than multitask. (How often do you “watch” a show while staring at your phone?) And it’s a source of authenticity–particularly on FX’s border drama, The Bridge, which returned for its second season this week. For the column, I talked to Bridge producer Elwood Reid; here’s an edited transcript of the interview:

Was the question of using Spanish and using subtitles ever an issue when you were developing the show or pitching it?

Elwood Reid: I don’t have a secret memo, but I think most networks would prefer that if it was in English. Now FX is a little bit different. They understood that we were pretty insistent on it being subtitled.

Myself, I’m from Ohio, so I think of my very Midwesterner parents sitting there going, “They’re speaking a different language on TV!” So when you say you’re going to do subtitles, it makes you think about scenes. I would try to figure out ways to get an English speaker in there so I can justify an English-speaking scene, because if I was being correct the show would be probably 60 percent in Spanish, and I think FX has an appetite for around 20 to 30 percent. So it’s this juggling act you’re always trying to do.

But in my mind nothing was ever wrong with [subtitles]. I think Netflix has shrunk the world a lot. If something is good, people don’t give a shit if it’s subtitled. Me, for example, I don’t watch American movies; I mostly watch Korean movies. So subtitles to me are just the way I take my movies in. I watch a lot of French gangster movies. I’m always watching with subtitles. If you want to find good shit you’re going to be reading subtitles, and I think that’s true in TV too–look at [the Danish political drama] Borgen and all these other series. Because of Netflix, people don’t think twice about it anymore.

Are you fluent in Spanish yourself?

No. Not at all. My name is Elwood Reid and I’m from Cleveland, Ohio. I struggle with English. Of course a lot of my cast is of Mexican descent, and then this year I hired a screenwriter in Mexico City, Mauricio Katz–he wrote Miss Bala. We write it in English because the network has to vet it in English; they have to know what we’re talking about. And then we translate it–and we translate it very specifically for that dialect of that area of Mexico.

I find dramatically we use [Spanish] a lot because when people are speaking Spanish in a scene, especially if there’s a gringo there, a white person, and they switch over to Spanish, it creates this really cool narrative tension: you’re leaning into the screen going, “Why the fuck are they speaking Spanish here? What’s going on?” We can use it as a very effective plot device, the language of exclusion, when people choose to slip in and out of their language.

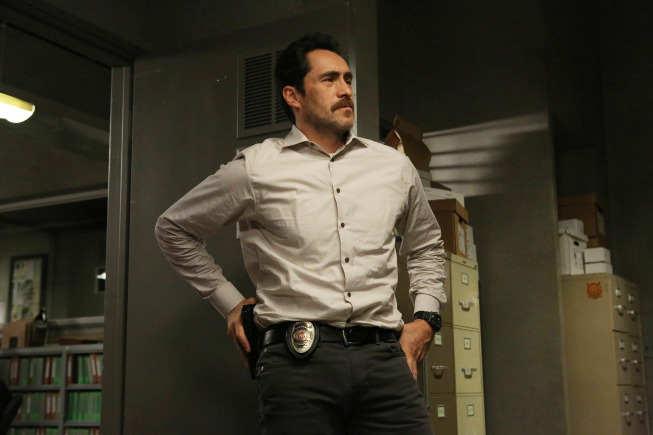

Are there advantages to being able to use two languages sort of at the character level? I’m thinking for instance of characters like Marco working on both sides of the border, and maybe see him in one way when he’s in his home element and then another way when he’s in El Paso?

Oh massively, yeah, and vice versa. Marco’s a good character because he passes in both places. And the actor himself, Demian [Bichir] and I talked about this a lot, he changes his demeanor when he’s around gringos. He’s a little more careful with his words. He’s a little more, I don’t want to say dispassionate but he’s not as direct. When you see [Marco] in Spanish he’s much more direct and there’s a sort of real edge to his character there. And he realizes, like we’re trying to play on the border, that he’s a guest over here in America. He feels the Other, he feels different, so he behaves accordingly–and vice versa, when Sonya’s over in Mexico, she’s a stranger in a strange land. They know she doesn’t belong over there because she’s blonde and blue-eyed, so they use the language to either exclude her or sort of try to suck her in by insulting her in Spanish.

You talked a bit about adapting the script to this particular region of Mexico. Did you hire writers with that in mind?

Well, it’s mostly about the actors, because where you fall down is–and again this is no fault of anybody but like a lot of times in Hollywood they’ll lump all the Hispanic people together. And there’s a massive difference between Puerto Ricans and Dominicans and Cubans and Argentinians and Mexicans. So one of the changes I made this year was with my casting people. We try to cast people who are Mexican or Mexican descent, and even better if they’re from Northern Mexico because it gives you a certain dialect.

You’ll see a little bit of the difference as the season goes on. There’s a character that’s introduced at the end of episode two who’s a kind of weird, slinky business guy played by Bruno Bichir; it’s Demian’s brother. So those two guys were raised together. He speaks a very high sophisticated Spanish, and Demian’s got a very sort of Norteño sort of gruff Spanish that he speaks. So they’re differentiating themselves within Spanish. And just because someone speaks Spanish–one of my actors is Puerto Rican, and Demian is on set with him busting his ass on how it’s spoken, not just Mexico City dialect but Northern Mexico dialect. Of course I have untrained gringo ears but even I’ve learned to hear it a little bit, like the rolling of the Rs the way a Puerto Rican will do. So Demian is my policeman on that.

And the addition of Mauricio Katz this year has really – when he does he translation he’s just not doing an idiomatic translation, he’s doing a nuanced, “Here’s the meaning in English and here’s how I translate it into Spanish.” And that’s been a huge step up from last year.

Do you get much feedback from Spanish-speaking or bilingual viewers on how the show uses the language?

Well, I think people like it. Again, I don’t have any data. But with Hispanic audiences is that Spanish-speaking audiences tend to stick to Telemundo or Univision. So we’re offering this kind of premium cable experience and we’re trying to extend a hand and going look: here’s this thing that’s being made by a mainstream cable network, and it’s depicting your world in your language. That Hunt for Red October bullshit where they speak Russian for two seconds and then all of a sudden Sean Connery is speaking English–that really pulls me out. Maybe audiences 20, 30 years ago were naïve with that, but I think as evidenced by [Americans following] the World Cup and all this stuff, the world has shrunk a lot. People don’t recoil at hearing a different language. If you give them the subtitles, they’re in. I mean, I really think of it as an asset for our show.

It seems like, if you’re looking for an immersive viewing experience, this forces you to have a more immersive viewing experience.

Yeah. Exactly. We play with it a lot, but [the amount of subtitling] is always a discussion with the network. There’s a number beyond which my show could be on Telemundo. So there’s that balancing act, we’re always trying to make it authentic without seeming bullshit. I don’t ever want someone to watch my show and go, “Why the hell are they speaking English here when it’s two Mexican characters in Mexico talking about something?”

[To read the full column, and the rest of TIME magazine, click here to subscribe for just $30 a year.]

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com