According to the trailer for their upcoming film, The Interview, James Franco and Seth Rogen (or at least the characters they play) will be sent to North Korea to assassinate Kim Jong Un. As you might imagine, the Supreme Leader isn’t exactly taking this in stride and has promised “merciless retaliation” against the U.S. for the faux assassination.

Extreme? Maybe, but then again you’ve never been fake-killed for millions of people around the world to see — and by Seth Rogen and James Franco no less. Maybe if it had been Jackie Chan or Jean-Claude van Damme (two of Kim’s favorite movie stars), things would be different, but no, it’s the guy who starts Twitter fights with Justin Bieber and the guy who posts the world’s most awkward selfies on Instagram.

And we’re not talking about any old leader here. This is Kim Jong Un, grandson of a god and friend to Dennis Rodman. He isn’t accustomed to being fake-insulted, let alone fake-killed. How would he explain it to all the friends who have to be his friends or else they’d be real-killed? Just something to consider.

Regardless of how you feel about Kim’s reaction, it is by all accounts the most outspoken response to a movie by the state (or in this case, head of state) that is the subject of the film. It is not, however, the first. Here are five other films that have been denounced, condemned or otherwise banned by governments who find that the movies hit too close to home.

Cry Freedom (1987)

Nominated for three Academy Awards in 1988, Cry Freedom chronicled the relationship of journalist Donald Woods (Kevin Kline) and activist Steve Biko (Denzel Washington) during apartheid-era South Africa in the late 1970s. Unsurprisingly, South African officials were somewhat uncomfortable with a film that depicted rampant discrimination, political corruption and racial violence in the segregated country. Though the movie was initially approved by South African censors, explosions and bomb threats accompanied the film’s debut, which may have helped spur the government to action. Stoffel van der Merwe, the Minister of Information, called Cry Freedom “crude propaganda” and said that the portrayal of South African security forces would undermine their public image.

Lara Croft Tomb Raider: The Cradle of Life (2003)

The sequel to Angelina Jolie’s first Tomb Raider film sparked the ire of Chinese officials, one of whom said, “After watching the movie, I feel that the Westerners have made their presentation of China with malicious intention.” The movie was partly filmed in Hong Kong, and was criticized by Beijing for making the country appear to be without a functioning government and instead run by secret societies. “The movie does not understand Chinese culture. It does not understand China’s security situation. In China there cannot be secret societies,” one official said.

District 9 (2009)

Neill Blomkamp’s allegorical film about aliens — or apartheid-era South Africa, if you look just a little closely — was nominated for four Oscars but was not a hit in Nigeria. According to the country’s Information Minister, Dora Akunyili, the Nigerian characters were portrayed as criminals and cannibals, and government officials also took exception to the fact that “the name of our former president was clearly spelt out as the head of the criminal gang and our ladies shown like prostitutes sleeping with extra-terrestrial refugees.” The film was banned in the West African country.

Argo (2012)

The 2013 Oscar winner for Best Picture told the story of the CIA’s mission to retrieve Americans trapped in Tehran during the 1979 Iranian hostage crisis. Though the film was widely criticized for historical inaccuracies, it was the Iranian government itself that had the strongest “Argo f— yourself” reaction. Mohammad Hosseini, the Iranian Minister of Culture and Islamic Guidance, denounced the movie as “an offensive act” that was motivated by “evil intentions.” Argo was banned in Iran and plans were made for the state-affiliated Arts Bureau to produce The General Staff, a film that would tell the true story of American hostages held in the country. Though the “big production” film was announced in January 2013, there have been few updates in the past year.

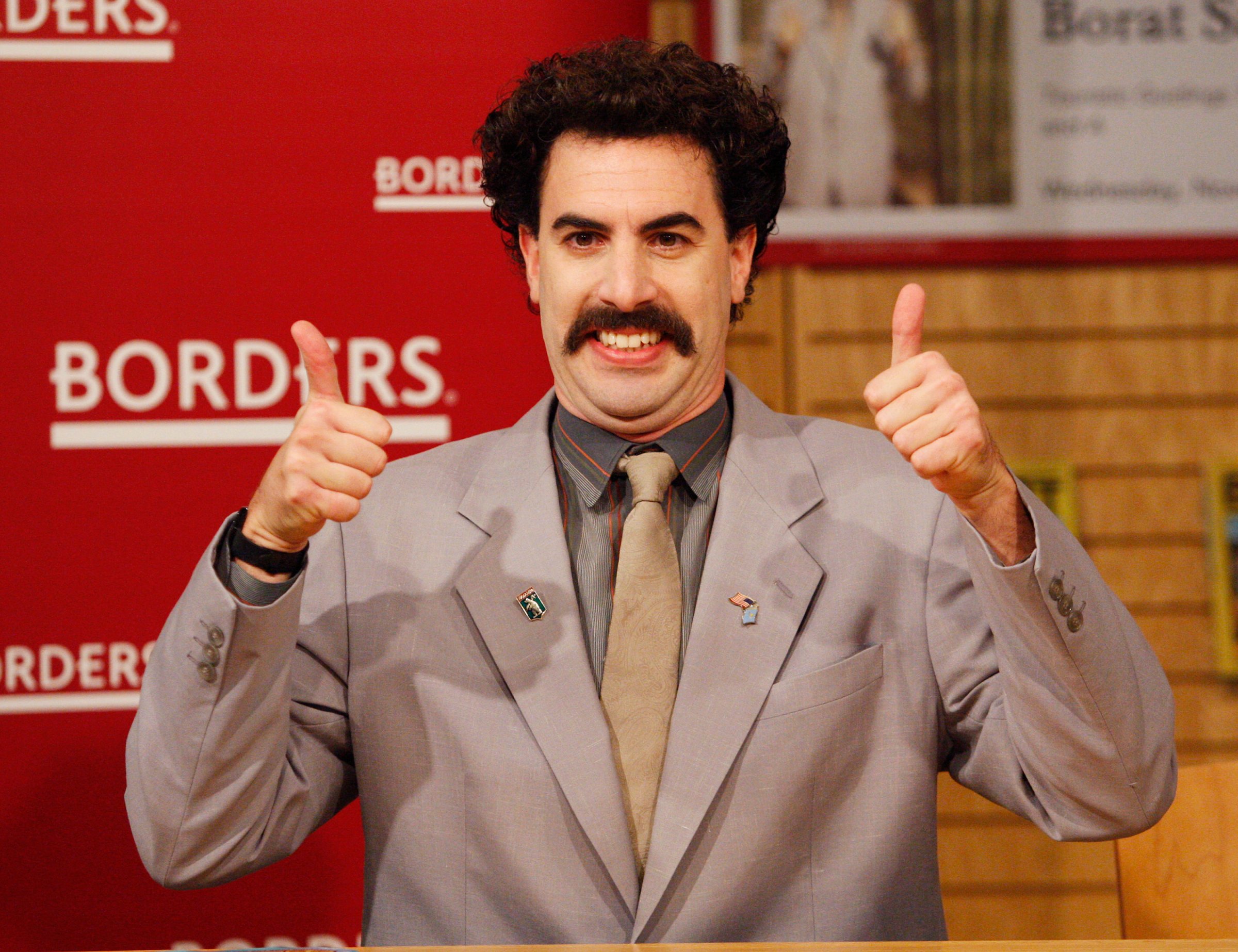

Borat (2006)

Borat presents the most complicated case of these controversial films. Borat the character — a misogynistic, homophobic and anti-Semitic news reporter from Kazakhstan, played by British comedian Sacha Baron Cohen — had been around since even before Baron Cohen’s Da Ali G Show debuted in the U.S. in 2000. The character quickly gained notoriety and garnered even more attention once it was announced that he would get his own movie. Initially, Kazakh officials were not at all pleased. “We do not rule out that Mr. Cohen is serving someone’s political order designed to present Kazakhstan and its people in a derogatory way,” Kazakh Foreign Ministry spokesman Yerzhan Ashykbayev said in 2005, a full year before the movie’s release.

As the film’s release neared, however, Kazakhstan seemed to soften its stance, in spite of threatened lawsuits and rumored bans. Though officials strongly urged that it not be distributed in the country (and it wasn’t), Erlan Idrissov, the Kazakh ambassador to the U.K., said he found the movie amusing in parts and wrote that it “placed Kazakhstan on the map.” In 2012, Foreign Minister Yerzhan Kazykhanov credited the movie with increasing visa requests to visit Kazakhstan by tenfold: “I am grateful to Borat for helping attract tourists to Kazakhstan.”

Though Kazakhstan ultimately changed its opinion of Borat, that seems unlikely to happen with The Interview and North Korea. Kim Jong Un’s repudiation is far from the country’s first condemnation of a film. The 2009 disaster film 2012 was reportedly banned by then-leader Kim Jong Il because it depicted a series of catastrophic natural disasters in 2012 — the very year that North Korea was meant to “open the grand gates to becoming a rising superpower,” coinciding with the 100th birthday of Kim Il Sung, the nation’s founder. Anyone caught with a bootlegged copy of the film was allegedly charged with “a grave provocation against the development of the state,” which could carry a prison sentence of up to five years.

If the punishment for holding a copy of a film that didn’t have anything directly to do with North Korea inspired that still a punishment, it would likely be wise for North Korean citizens to stay as far away from The Interview as possible.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com