Had it not been for France’s violent riots of 2005, JR would be just another street artist making his passing mark on rooftops, pathways and tunnels. Instead the 31-year-old Parisian, who is known only by his initials, is an internationally recognized photographer and the first to see his work go up on the walls of one of his hometown’s most historic monuments, the Pantheon.

JR’s rise from the streets began in 2004, when he photographed the mostly immigrant and minority residents of Les Bosquets, a rough neighborhood in the suburban town of Clichy-sous-Bois, a few miles outside Paris. By pasting their portraits on the sides of the derelict buildings they inhabited, JR–himself of Tunisian and Eastern European descent–sought to allow his subjects to claim their homes, symbolically if not in reality. The ongoing tensions in Les Bosquets exploded a year later following the death of two teenagers of immigrant descent. Zyed Benna and Bouna Traoré, thinking the police were chasing them, had taken refuge in a power substation and were electrocuted.

The community’s anger transformed Clichy-sous-Bois into the epicenter of France’s worst riots in a generation, and when journalists first entered the town in October 2005, they faced not only angry young men setting cars alight but also JR’s giant portraits. “That’s how people actually discovered my work,” JR says. “That’s when I understood the power of these images, and that’s when I started traveling around the world. I wanted to see all the places the media was talking about. I wanted to work with the communities there.”

Since then, JR has brought his art to places all over the globe–from the favelas of Brazil to the shantytowns of Liberia, the slums of Cambodia and the concrete jungle of New York City. His trademark: large-scale, black-and-white portraits of the people he meets along the way–many of them smiling, some grimacing. His humanist bent and street artist’s sense of showmanship won him a $100,000 TED prize in 2011 and has led to collaborations with documentary filmmakers and even the New York City Ballet.

Now, JR is back in Paris to unveil his most ambitious work yet, cloaking the Pantheon in thousands of the self-portraits he has solicited from people around the world. Built in the 18th century, the Pantheon is a mausoleum for French luminaries: Victor Hugo, Alexandre Dumas, Voltaire, Marie Curie and an additional 68 of the country’s most celebrated politicians, writers, artists and scientists are buried there. This year it begins an unprecedented decade-long structural renovation, and from now through October the building and its scaffolding will serve as a canvas for JR’s vision.

“A lot of monuments in Paris usually display advertising on their scaffolding,” JR says. “When the Center of National Monuments approached me with the idea of taking over the Pantheon’s scaffoldings, their mind was already set: they wanted me to do it, and they really kept an open mind. I had carte blanche to do whatever I wanted.”

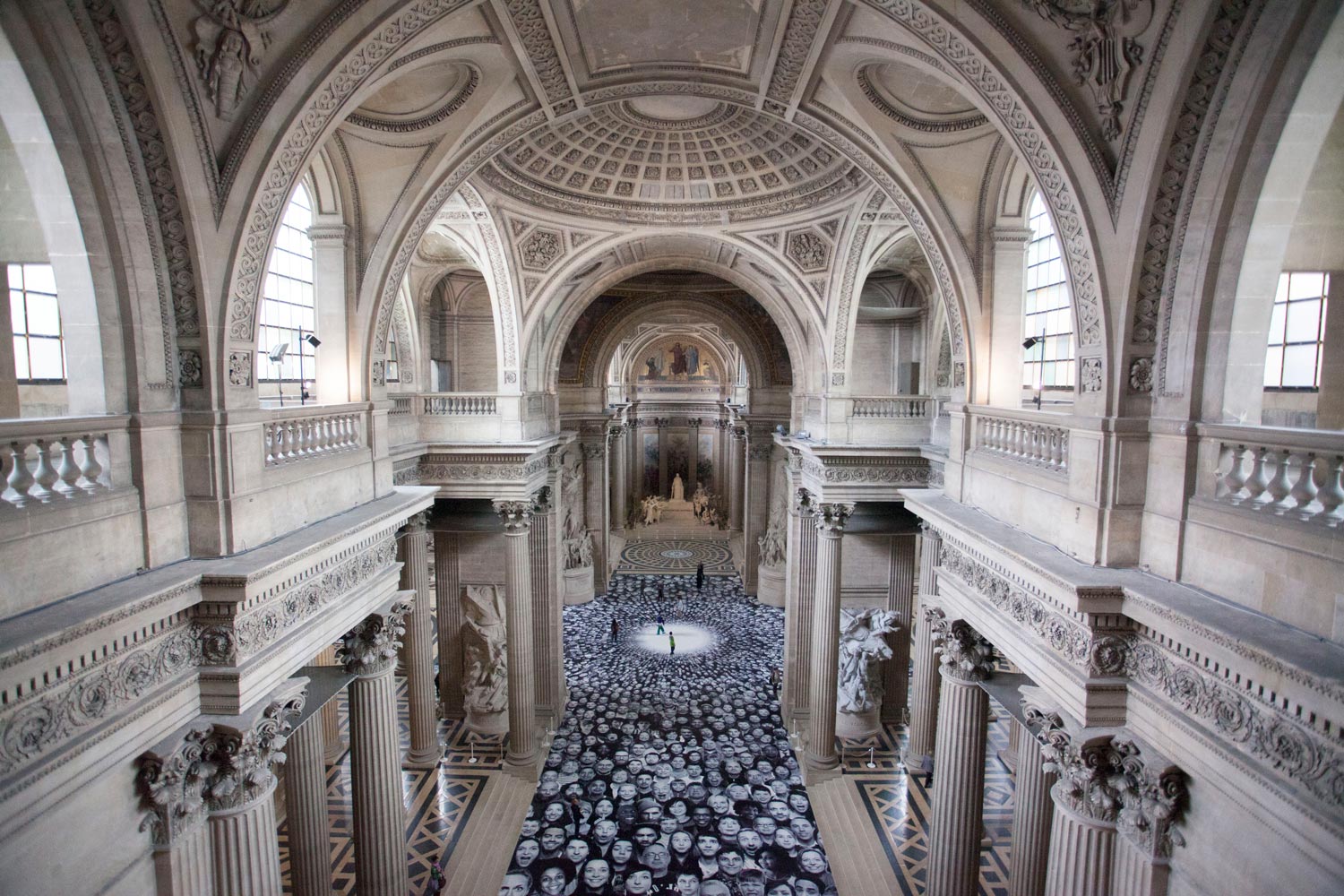

The result is 4,160 black-and-white portraits, which he collected online and with a roving studio built into a van that he drove around France. He has now pasted the images around the building’s dome, inside its cupolas and on 8,600 sq. ft. (800 sq m) of floor in the nave. “What I wanted to show with this artwork was that we, the people, have a voice, and that that voice can make a difference,” he says. “Among all these people, some will become great men too.”

The portraits range in size from a tiny 8 by 8 in. (20 by 20 cm) to a giant 6.6 by 6.6 ft. (2 by 2 m), and the outdoor mural composed of these hundreds of smiling faces can be seen from miles away. Inside, the installation takes on immense proportions. (JR says one of his goals has always been to overwhelm his audience.) Walking over thousands of selfies gathered in this civically sacred space, you begin to see them as a personification of France’s motto–“Liberty, Equality, Fraternity.”

From Graffiti to Guerrilla

Born in 1983 to a Tunisian mother and an Eastern European father, JR grew up in a quiet Parisian suburb, which he refuses to name for fear of revealing clues about his identity. (Though he allows himself to be photographed and interviewed in black sunglasses and a fedora, he veils his identity to maintain his privacy.) What is known is that in 2000, after spending years tagging his initials around the streets of Paris, he came across a camera left behind on the Métro. It changed his life. The lens replaced the paint cans, and the young graffiti artist turned photographer started documenting his friends, creating 8-by-12-in. (20-by-30-cm) posters he then pasted onto the same walls he used to paint.

In 2007 he made headlines with his Face2Face project in Israel and Palestine. This time, JR pasted portraits of people living on both sides of the separation wall in a bid to show how alike they were. His message was clear, but the French photographer soon realized he might not be the best spokesman for Middle East affairs. “When I was on my ladder pasting these images on the wall, I wasn’t able to answer some of the journalists’ questions, so the people whose photographs I was pasting started answering them for me,” he explains. “I loved hearing their answers because it showed me what this project meant to them. Suddenly, what was a super egocentric project became something more meaningful.”

Since then, JR has sought to remove himself from the photographic process. With the money he was awarded from the TED Foundation, he called for people to stand up for what they cared about “by participating in a global art project to turn the world Inside Out.” The concept was simple: JR would print and ship, to anywhere in the world, a poster-size version of any portrait uploaded to his website–as long as the subject also shared a statement about what he or she believes in. Suddenly, thousands of people began to replicate JR’s style, pasting images of themselves–whether printed by JR or not–on walls and buildings.

“It’s been amazing,” he says. “People in 130 to 140 countries around the world have been pasting posters in tens of thousands of cities, in places I’ve never been, from Afghanistan to Peru.”

JR regularly visits cities around the world with different versions of his mobile photo booth. Last year he stopped in New York City for a week, inviting hundreds of people–New Yorkers and tourists alike–to join him in pasting their portraits all over Times Square. At first the location intimidated him, not because of its size but because of the wealth of advertising. “Then I realized that the challenge wasn’t to compete with those ads,” he says. “The challenge was to reconnect New Yorkers in a place where they don’t connect. The setup became an excuse for people to talk to each other, especially when they’d wait in line for hours at a time. I think that their best memories weren’t about the photos but about the people they’d met that day.”

Pictures on Point

Jr’s next site-specific work in New York City shared that drive to connect. When he was asked last February to take over the floor of the David H. Koch Theater, home to the New York City Ballet, he conceived an artwork that could be seen in its entirety only from the fourth floor, where the seats are cheapest. Suddenly, the upper balcony became the theater’s hottest ticket, and patrons eager for the aerial view mingled after performances in ways they never would have otherwise.

The success of that work made him crave an even closer link to the ballet. “I really wanted to touch the stage,” he says. “But in order to touch the stage, you have to be a choreographer.” So when Peter Martins, the troupe’s master in chief, offered him the chance to produce his own ballet, he didn’t hesitate. Enlisting the help of Woodkid, a French director and songwriter, JR went back to the events that shaped his artistic identity. In an eight-minute piece, he reconstructed the story of the 2005 French riots, using a journalist as his main character to show how the media had failed to understand what really happened in Les Bosquets.

This summer he’ll take that project to the big screen, partnering with Grammy Award winner Pharrell Williams and film composer Hans Zimmer to produce and direct his first fictional movie–and he’s bringing the New York City Ballet’s dancers with him. “I’m re-creating the ballet I directed in New York and bringing it where the riots actually took place,” he says. “It’s a part-documentary, part-fictional piece, and Pharrell and Hans will take care of the music.” He relishes the idea of returning to Clichy-sous-Bois. “That’s what defines me as an artist,” he says. “Every time I think I’m closing the book on Les Bosquets, I find that there’s something else to say.”

Others have been equally inspired to continue the artist’s message–and his methods. In May, activists in Pakistan used Inside Out to install a large-scale portrait of an orphan to condemn U.S. drone strikes. “That massive image can be seen from a drone. They’ve done it to say that they’re here, that they exist,” JR says. “In this case, I didn’t actually print that image. They’ve respected the rules of the Inside Out project, but they printed it themselves and put it up themselves. It really shows that Inside Out is not mine anymore and that it will live on. The idea cannot be killed.”

As for what he’ll do after the Pantheon exhibit comes down in October, he’s still seeking an answer. “I dream of bringing photography as sculptures, permanent objects that could be displayed in cities and experienced by everyone,” he says, “but I haven’t found a way to do it yet. I hope I’ll make it happen.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Dua Lipa Manifested All of This

- Exclusive: Google Workers Revolt Over $1.2 Billion Contract With Israel

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- The Sympathizer Counters 50 Years of Hollywood Vietnam War Narratives

- The Bliss of Seeing the Eclipse From Cleveland

- Hormonal Birth Control Doesn’t Deserve Its Bad Reputation

- The Best TV Shows to Watch on Peacock

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com