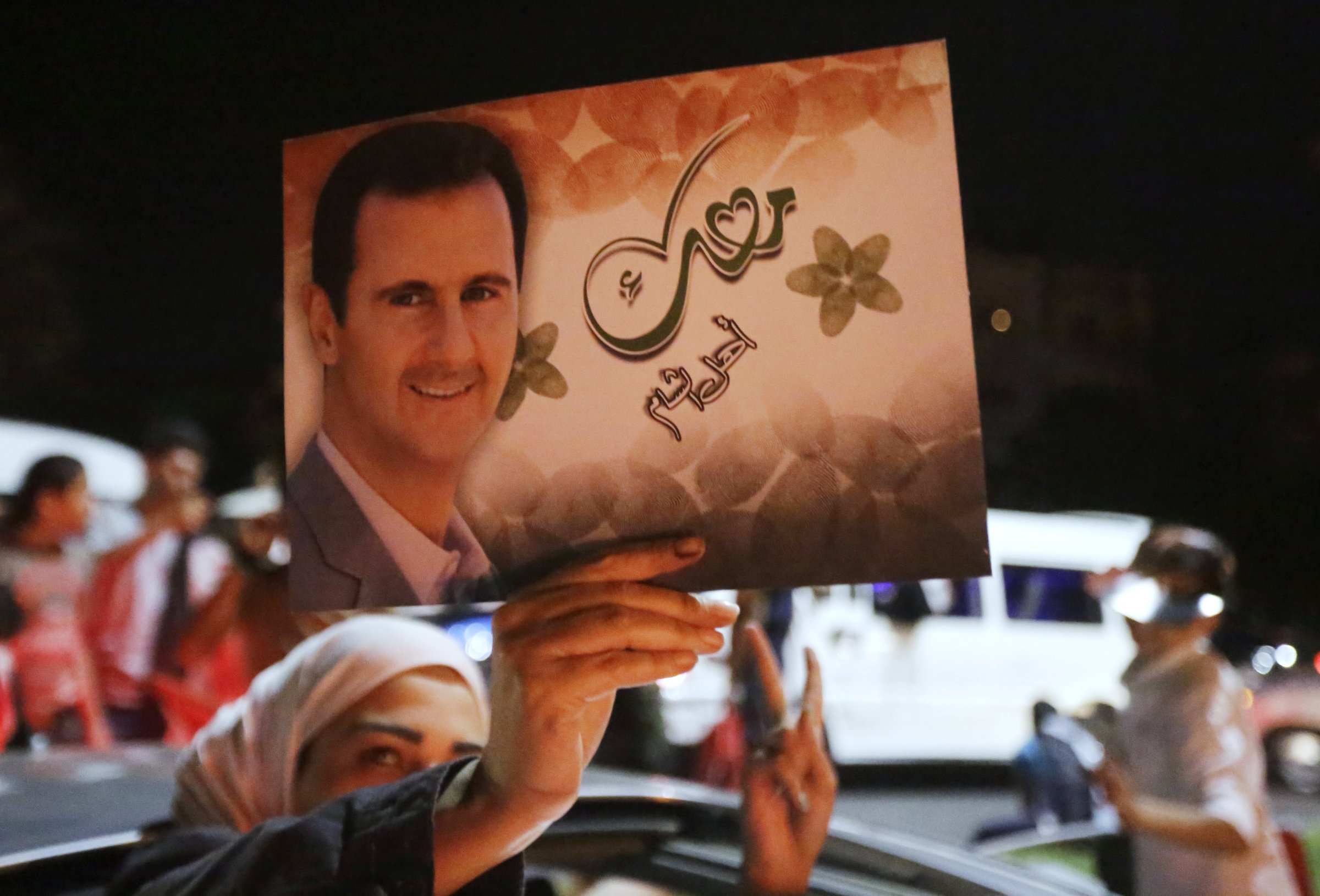

A sweep in Syria’s presidential election last week, no matter how roundly denounced as fraudulent by the U.S. and other Western powers, seems to have put President Bashar Assad in a magnanimous mood. On June 9 state TV announced a general prison amnesty, in which Assad promised to commute death sentences to life imprisonment, reduce jail terms and even pardon those accused of joining “a terrorist organization” — regime-speak for members of the armed opposition.

If applied with the same sweeping generosity as the announcement suggests, the amnesty could result in tens of thousands of prisoners being released back into Syrian society. But families with loved ones in prison may want to temper their expectations a little bit longer, warn human-rights groups. Previous amnesties fell short of their promise, and presaged an even greater crackdown on human rights. And ambiguities in the wording of the current amnesty offer, including several nonspecified exemptions, could mean that many remain behind bars for years to come.

“Let’s see what happens on the ground first,” says Neil Sammonds, Syria researcher for Amnesty International. “If this is carried out, then of course it will be welcome. Still, it only goes a small way to addressing the concerns we have about the numbers in Syria’s prisons, their access to lawyers, their adequate medical care, their right not to be subjected to torture and the prompt investigation of those accused of torture.”

According to state television, Justice Minister Najem al-Ahmad said the decree had been issued in the name of “social forgiveness [and] national cohesion,” as “the army secures several military victories.” In short, it’s a gesture meant to consolidate support as the regime readies for new military assaults on areas still out of government control.

It could also assuage a significant problem: massive prison overcrowding. It is unclear, exactly, how many Syrians are currently under some sort of detention. Former U.N. envoy Lakhdar Brahimi, who stepped down in May, said in an interview with the German magazine Der Spiegel over the weekend that Assad “knows that there are 50,000 to 100,000 people in his jails and that some of them are tortured every day.” Whatever the numbers, the conditions for those who do end up in detention are abysmal.

Antigovernment activist Samer — who asked not to be identified by his full name for security reasons — estimates that there are about 10,000 detainees in the central prison in Homs, his hometown and Syria’s third largest city. “It’s overcrowded,” he told TIME via Skype. “The space is too small for the number of prisoners they are holding there.” Bilal Ghalioun, who escaped from detention in Homs in April, described jail cells packed so tight that “we couldn’t even sleep on our backs; we had to crush together on our sides,” in a recent interview with TIME.

On paper, the amnesty offers a pardon to foreign fighters who have joined the rebels aligned against Assad, as long as they identify themselves within 30 days. Army deserters have 90 days to hand themselves in, and those over the age of 70 or suffering from incurable diseases would be released. Traffickers of drugs and weapons will have their terms reduced, the amnesty promises, and even kidnappers will be let go as long as their victims are freed.

But as far as human-rights advocates can tell, the new amnesty only refers to prisoners who have been formally charged in Syria’s courts. That means the untold thousands who are under illegal detention, either with the military, the intelligence services or the shadowy paramilitary groups that have sprung up in the past few years, may not be affected at all.

“The criminal-justice system in Syria is an elastic band, it can be stretched or tightened however the security or judicial forces decide best suits their needs,” said Sammonds, of Amnesty International. Ghalioun, who survived torture, starvation and abuse for two years in various detention centers in Homs, was never formally charged with a crime. That made his eventual escape easier — his family was able to bribe a prison official — but others like him are unlikely to see freedom under Assad’s new amnesty.

— With reporting by Hania Mourtada / Beirut

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Dua Lipa Manifested All of This

- Exclusive: Google Workers Revolt Over $1.2 Billion Contract With Israel

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- The Sympathizer Counters 50 Years of Hollywood Vietnam War Narratives

- The Bliss of Seeing the Eclipse From Cleveland

- Hormonal Birth Control Doesn’t Deserve Its Bad Reputation

- The Best TV Shows to Watch on Peacock

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com