Blake Nelson is the author of many critically acclaimed novels, including Recovery Road, the seminal coming-of-age novel Girl, and Paranoid Park, which was made into a feature film by Gus van Sant. His subject matter tends to emphasize the “adult” in Young Adult fiction, tackling mature themes like sexuality, death and addiction in a frank, sparse and unyielding manner that thrills his audience. Even as a 40something man, Nelson is able to wholly inhabit his always teenaged, frequently female protagonists, bringing them to life in a starkly realistic manner, sure to open the eyes of more than a few parents.

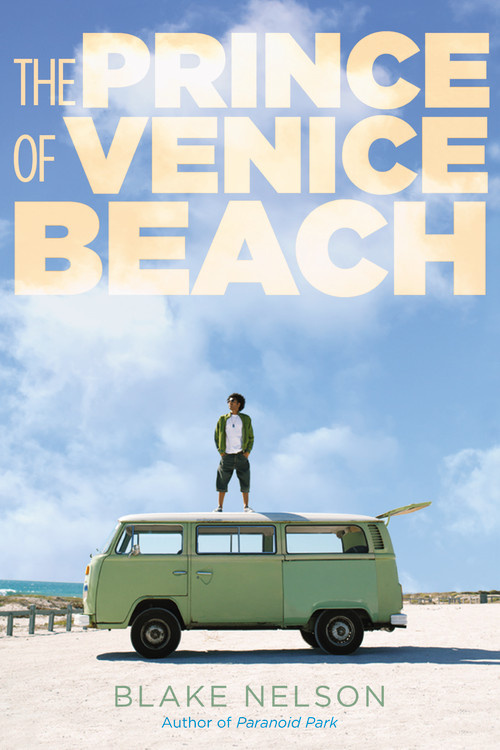

His latest novel, The Prince of Venice Beach, focuses on Robert “Cali” Callahan, a 17-year old runaway bunking down in Venice Beach, Ca., wiling away his hours roaming the boardwalk on his skateboard, playing basketball and trying to avoid trouble. When a private investigator asks him to help track down another runaway, Cali finds out he has a knack for finding people. At first he’s excited to earn money as a boy detective, but when asked to help find a beautiful rich girl who doesn’t want to be found, he starts to question the motives of the people hiring him and he has to decide where his loyalties lie.

TIME talked to the author about his new book, Recovery Road getting a TV pilot, the rebirth of YA, and why you should always have librarians in your corner.

You’ve written books based in your hometown of Portland, Oregon, before, and now you live in Venice and your new book is based there, how do you feel that location affects what you write?

One thing I can say is that I lived in New York for about 15 years and I never felt that I could write about it. There was just something about it. But, Venice, I just took to it right away. There was also something about the circumstances about the kid being a runaway and adrift that I could immediately relate to. I was just a transient there myself, I was just kind of checking it out. I couldn’t act like I knew Venice backwards and forwards, but I know it as well as the character does. Cali came to Venice and really changed his life. In a weird way he’s had that classic California experience where he’s reinvented himself. I don’t go into what his life in foster care was like, but he was in the social service system in Nebraska and it was probably horrible. Then he comes out here and he gets to play basketball and surf and live a dream life. But, while I was writing the book, I wondered if it’s a good idea to tell the teenagers who will presumably be reading this book, that if they want to have a good life, they should run away and move to Venice?

But you dispel that in the first few pages, where the runaway from Seattle thinks it will be great, but ends up wanting to go home almost immediately after arrival.

Right, that’s right.

Do you think about the reader when you’re writing?

No, I don’t really think about the reader, I just think about the story. One of the interesting things about writing this book was that there is something about Cali’s situation — I’ve never done anything at all like what he’s done — but it echoed in someway my own experience. He triggered something in me, in my own personality, I really wanted to be Cali and I really wanted to see what he would do and I was really excited. Every couple of years someone tries to write a book about runaways or homeless youth and it’s a disaster, commercially. So I started writing this just to see if I could pull it off, just to try it out and see if it would work. I wrote the first two chapters and thought, eh, that’s not that great and put it away. At some point I took it out and wrote a little more and then it triggered something in me, in a good way, and suddenly I was Cali. That was the fun of the book! I hadn’t really written a mystery before, I just kind of got swept into it. I didn’t know what I would say about being homeless, because I don’t know much about it, but then I told my editor to never use the word “homeless” when describing Cali, always use, “runaway”. Runaway sounds more energetic, more exciting, more pro-active. Huck Finn was not “homeless”. He was a “runaway”.

What was your favorite scene or part of the book to write?

My favorite relationship is between Cali and Strawberry, the young girl who really doesn’t know what she’s doing. Every time I could come back to that I really enjoyed it. Sometimes I’ll flip through the novel and just want to read all the parts about Cali and Strawberry. A lot of the book is plot, but the relationship between Cali and Strawberry just feels real. If I wasn’t writing a mystery, I would write a whole book about that relationship. I just like the sweetness of it and the way they look after each other. I’ve read a few reviews that said this relationship isn’t realistic, but I think it is. Having hung out with some homeless people, I know they form relationships with each other and that they do look after each other. I think it makes it real. I didn’t become a writer to make money, I write to get at things like this, and when I can, it makes it worth it.

You read your own reviews?

I do! They are mostly good and the ones that are bad tend to be helpful.

What appealed to you about writing a mystery?

Being in LA had a lot to do with that. Every writer, when they come here, they soak up a little of that Noir Vibe. That’s really what LA feels like. And when I thought of Cali trying to find people, I could see that I was heading down that “mystery road”.

Did you go out and do much research?

I walked around Venice a lot. And when I was in the punk scene in Portland, there were always a lot of homeless— or borderline homeless, at least — kids hanging around in that scene. A couple of years ago, I went and talked to a girls in a juvenile correctional school and I told them that I was writing about street kids and I asked them what some cool street kid names were and I thought they would tell me a couple, but I went home and they wrote me a letter with a list of like a hundred street kid names. I forgot I had this list when I was writing, but I just found it the other day and they are great. I didn’t get to use the names this time, but if they let me do a series of these books, I will definitely use them.

What were some of them?

Black Barbie, Froggie, Trouble, Bubbles, Hawaiian Mitch, Keycatch, Polar Bear.

What would be your street kid name?

Oh, I don’t know. Maybe someone else has to give you your street kid name.

Your book Recovery Road is being made into a pilot for ABC Family. What’s that book about?

Yes, they are shooting a pilot. It’s about two teenagers who fall in love in rehab. One of them — the girl — is from a very affluent neighborhood and the boy is from a lower class background. That doesn’t really matter when they are in rehab, but when they get out of rehab the differences in their backgrounds really start to come into play. She manages to not drink and not party and realizes that she wants to go to a good college, whereas the boy has a lot more trouble staying sober. It’s very gritty and it’s my best book since Girl, in fact a lot of people say it’s better than Girl. You should read it.

After the success of The Fault in Our Stars, Divergent and The Hunger Games, there has been a lot of interest in young adult literature, but you’ve been writing YA for years. Are you finding that your books have a new audience?

Yeah, I do. The fun thing with YA now is that adults read it, too. The tone of my books is more mature and I’m able to get away with that because the young adult world is so big now. I probably couldn’t have really survived in the young adult world in the past, but because it has grown, I can. I don’t have a huge audience of 13-year old girls, but there are a lot of librarians, so many adults, so many older teenagers reading YA now that my coming-of-age stories can ride the coattails in. Now, someone like John Green, he’s just super talented and he would be fine no matter the size of the YA market.

As an author known for writing YA, do you have people asking when you are going to write an adult book? Or has that faded as YA becomes more popular?

I don’t think the movement between those two worlds is as easy as people think. I’ve tried to do that, I’ve tried to do the adult thing, but if you write about teenagers and you’ve worked on it and really developed it, it can be hard to transition to writing about adults. James Patterson has made a little fortune writing kids books. Judy Blume did it, but I feel like you get kind of stuck in your thing. Not in a bad way, but if you work at something a lot and get good at it, it can be hard to switch. I wrote screenplays for awhile and it took a long time to get that out of my system. I had to totally stop and I had to rebuild my chops for writing prose. I hadn’t written any prose for almost a year and then when I sat down to write again, I couldn’t do it. It scared me! I had to rebuild. I think going between adult and young adult is a lot harder than it looks.

There’s been a lot of buzz about whether adults should be reading YA after that article in Slate came out. What’s your take on it?

I think it’s great that adults are reading YA. There’s a freshness to the genre. To me it feels like a “back to basics” movement. Strip away the pretension, renew the energy, make books FUN again.

Do you think it matters who your designated audience is?

I think it does. I would love to write a book about adultery, or the stuff that happens in mature relationships, or some complex, mature, novel about three generations of immigrants from Europe, but I can’t really do that, because I’m in the young adult world. It’s a little bittersweet that you’re closed off from stuff like that, but at the same time, in a classic literary career you don’t get to write ten coming-of-age novels, you get to write one. I’ve been able to write 12 coming-of-age novels!

Have you come of age?

Not yet!

MORE: Here Are the 15 Best Books of 2014 (So Far)

MORE: REVIEW: Save the Date: Jen Doll’s Wedding Survival Guide

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com