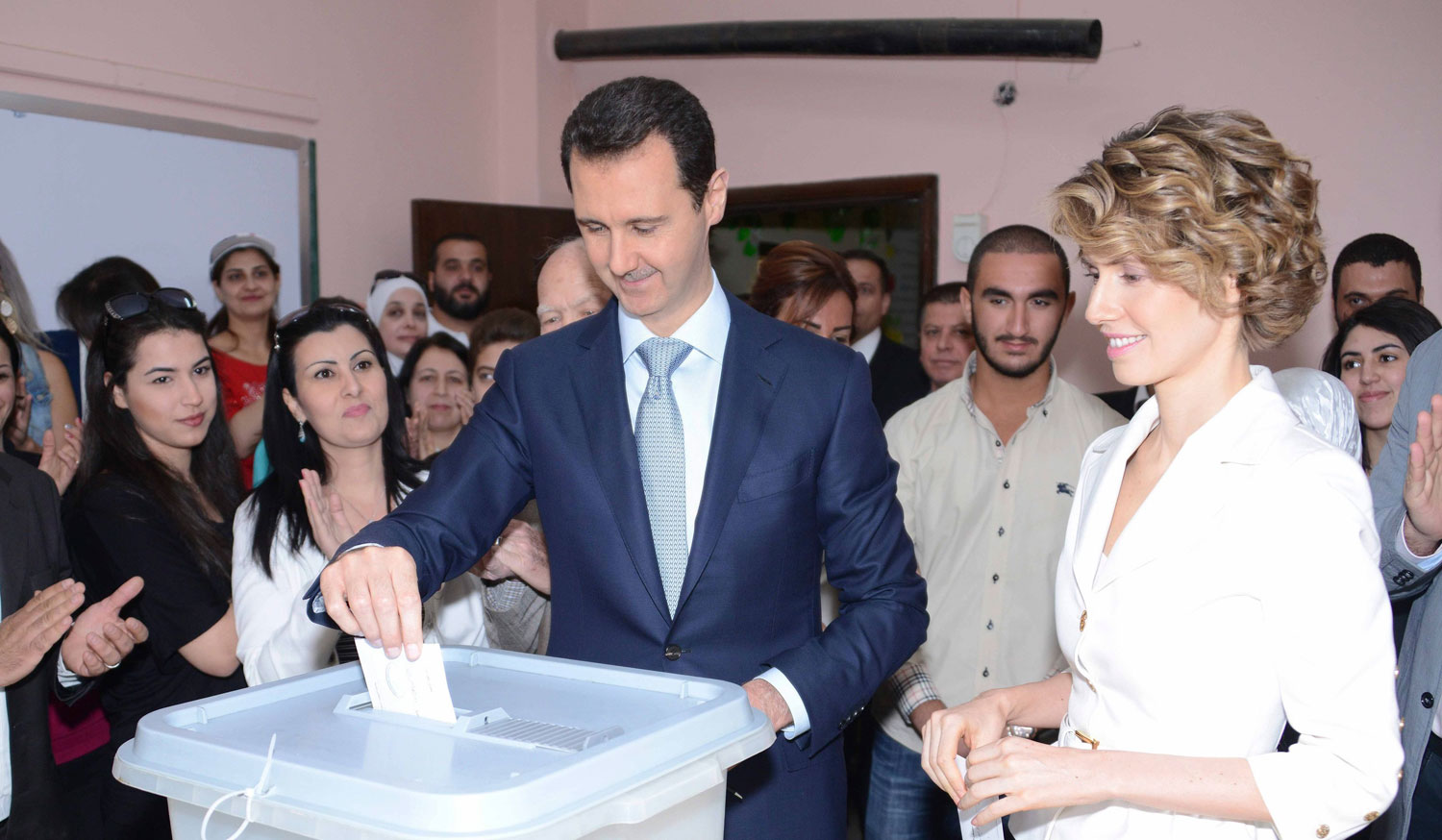

Election observers from North Korea and Zimbabwe monitored the fairness of the voting. Government employees shuttled other government employees to the polls by the busload. Soldiers granted passage through the ubiquitous military checkpoints only upon presentation of ink-stained fingers – proof of having voted. All told, Syria’s presidential election on June 3 was a flawlessly stage-managed affair designed to not only grant President Bashar Assad a third, seven-year term, but to do so with a resounding mandate. The vote may have been called a “charade” by the political opposition in exile and “farce” by the United States, but in government-controlled areas, supporters of President Bashar Assad turned out in such high numbers election officials say they were forced to extend voting until midnight. Some polling stations claimed that they ran out of needles especially stocked for voters who preferred to mark their ballots in blood, rather than ink.

Within three hours of the polls’ closing, election officials started tallying the votes. Nobody doubts that Assad will win, but the questions now are by how much, and with what kind of turnout. Results will be announced in the coming days.

With large swathes of the country under rebel control, and more than nine million Syrians displaced from their homes as a result of the civil war, a true national election was an utter impossibility. Citizens from areas that have withstood months, if not years, of military attacks, aerial bombardment and siege warfare are unlikely to have voted in support of a President who responded to 2011’s peaceful protests with a vicious military crackdown. But they were not allowed their say. Residents of pro-government areas more than made up for their silence, voting out of fear, out of compulsion and even out of enthusiasm, setting the stage for continued conflict as Assad prepares for his July inauguration.

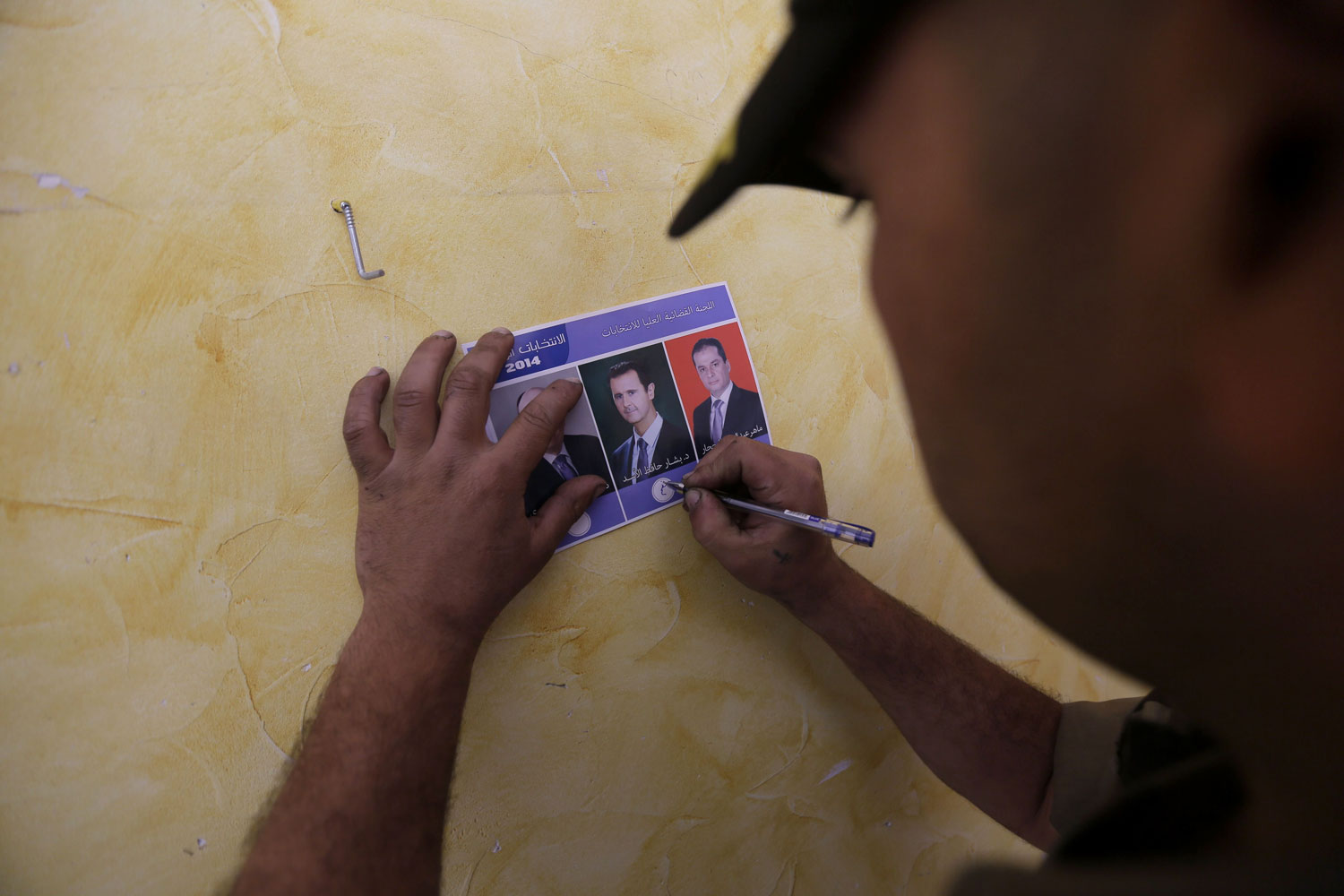

The election was nominally between Assad and two little-known, government-approved challengers: Maher Hajjar and Hassan Nouri. But throughout the campaign, the election was cast as choice between Assad and radical elements of the armed opposition that have terrified many Syrians with their brutal tactics and pledges to implement Islamic law. So great is the fear that it is quite conceivable that Assad could have won, even in a perfectly transparent process. In the 2007 referendum he won with 97.62 percent of the vote; cynical Syrians assume that this year his numbers will be lower, not because of reduced support, but in order to cast a veneer of legitimacy over the process. “I think 70-something percent would look best,” says one former regime official, who spoke on condition of anonymity. “But could his ego handle it?”

With informants in virtually every apartment building, school and workplace, Assad opponents tell TIME they were afraid not to go to the polls, for fear that a refusal to vote could be interpreted as dissent. “There are many eyes for the regime,” says Arts al-Shami, a 31-year-old employee of a non-governmental organization in Damascus, via Skype. Government employees and students, he said, felt they had no choice but to vote, for fear of losing their jobs or being expelled from school. A 75-year-old from the central city of Homs, who asked not to be identified for security reasons, fretted that his son and wife, who work in government offices, were being forcibly transported to polling centers. He planned to stay home. “I don’t believe our voices can change the status quo anymore, but if I can’t get rid of corruption then at least I won’t participate in it.”

Other Syrians participated with zeal, equating a refusal to vote with leaving Syria in the hands of radical Islamists. Besides, says 26-year-old accountant Baraa via Skype, Assad’s Syria is a fine place, as long as you don’t dabble in politics. Via Skype, from his hometown of Aleppo, he expressed confidence that things would get better after the elections. “The regime is on a promising path even if the change doesn’t happen overnight.” Even though he spoke in support of Assad, he did not want to give his full name out of fear for his safety.

For Assad, successful elections are an integral part of his victory. With what he terms a clear mandate, even if it comes from loyal supporters, he will try to justify continuing his brutal military campaign by citing popular support. And with no real alternative to his leadership, foreign countries and the United Nations will have no choice but to deal with him on issues of humanitarian assistance, refugee repatriation, peace talks and eventual reconstruction. Zeina, a 27-year-old interpreter, described Damascus as a city overtaken by “ultra-ridiculous pro-Assad festivities.” She complained, via Skype, of a headache brought on by pro-Assad chants in the streets. “We’re stuck in a dystopian nightmare,” she said, asking to go by her first name only, for security reasons. “There’s a general sense of defeat. The revolution is coming to an end and Assad has managed to triumph.”

The Assad regime may not be able to engender true, nationwide support, but with these elections, it has paved the way for a coronation.

With reporting by Hania Mourtada / Beirut

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com