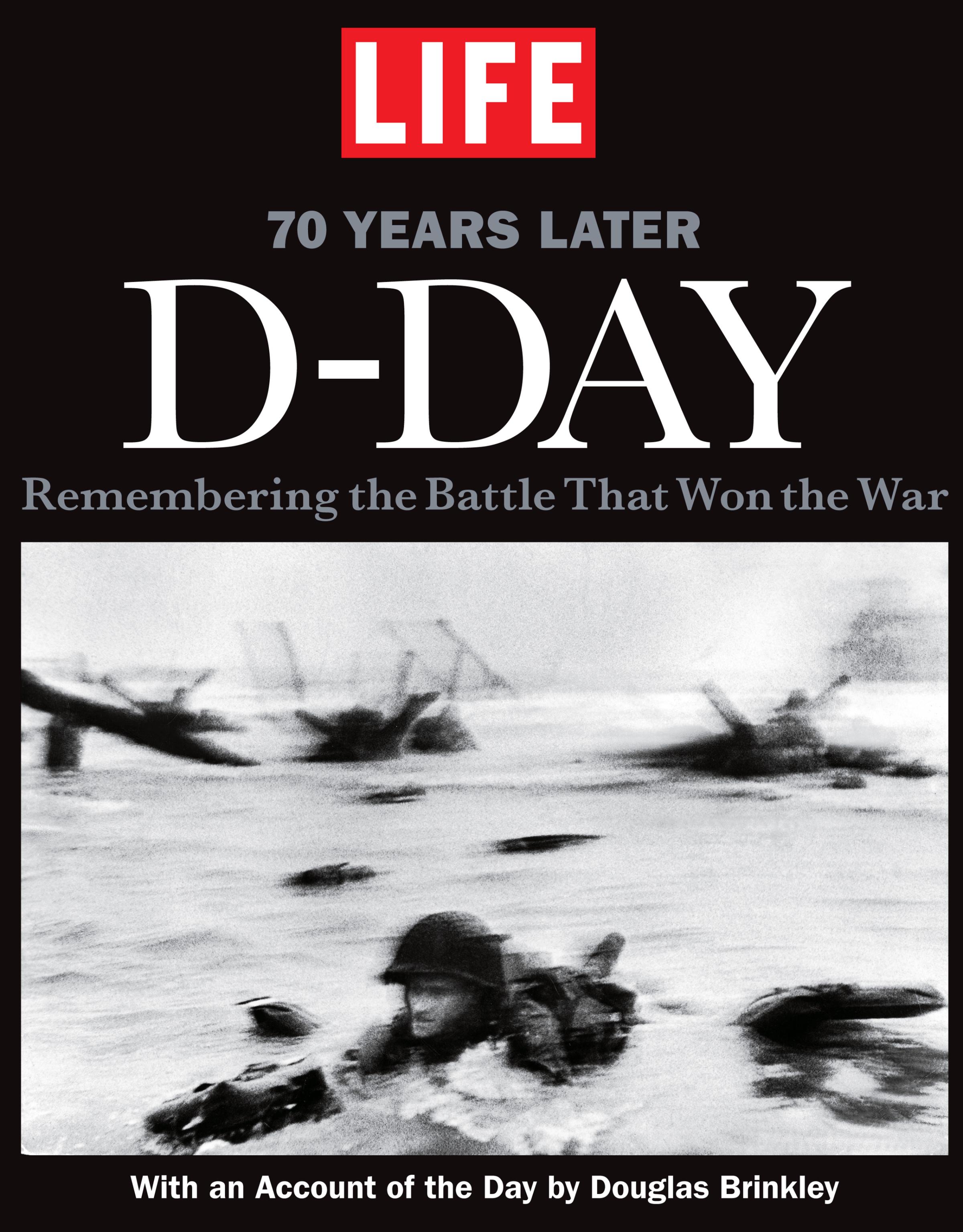

This essay was first published in LIFE D-Day: Remembering the Battle that Won the War–70 Years Later.

On June 6, 1944, Franklin D. Roosevelt went to bed just after midnight. The D-Day invasion was under way, but the

President was nevertheless determined to get a little shut-eye. His wife, Eleanor, was more anxious. She paced around the White House, waiting for General George C. Marshall to report on how the Allied forces fared on the five battlefield beaches of Normandy: Omaha and Utah (Americans), Gold and Sword (British), and Juno (Canadians).

At three a.m., she woke up Franklin, who put on his favorite gray sweater and sipped some coffee before starting a round of telephone calls that lasted over five hours. When FDR finally held a press conference late that afternoon on the White House lawn, he talked about how distinctive D-Day was in world history. Crossing the turbulent waters of the English Channel from Dover to Pointe du Hoc with the largest armada in world history—the ships carried more than 100,000 American, British and Canadian soldiers—was truly an event for the ages. Later that evening Roosevelt addressed the world on the radio. He evoked the Fall of Rome before boasting that God had let the Allies prevail over the “unholy forces of our enemy” in Europe. Roosevelt was basking in the glow of one of history’s seismic shifts.

The following day, June 7, newspapers were full of mind-boggling factoids and statistics about how D-Day had succeeded. One number that didn’t appear was 36,525. Readers might guess that the number represents the tally of soldiers who landed at Omaha Beach or the number of ships and aircraft used in the cross-Channel operation or the number of German defenders or the number of casualties or any number of other things associated with Operation Overlord. But 36,525 is simply the number of days in a century, and of all the days in the 20th century, none were more consequential than June 6, 1944. Some might argue that certain inventions and discoveries during that great century of innovation should be deemed the most important—like Watson and Crick’s reveal of the double-helix structure of DNA or all of Einstein’s contributions—but other nominees flatten when one asks, “What if D-Day had failed?”

Usually, one day in a century rises above the others as an accepted turning point or historic milestone. It becomes the climactic day, or the day, of that century. For the 19th century, I’d choose July 3, 1863, when the youthful United States of America—split in two by a great Civil War—was finally set on the healing path that would allow it to remain a single nation. We can only imagine the history of the free world today if, at the end of the Civil War, there had been two countries: the United States and the Confederate States of America. And what date in the 18th century can beat July 4, 1776? In the 15th century, was there a more important date than October 12, 1492, when Christopher Columbus first sighted the New World? And the course of Western civilization was forever changed on October 14, 1066, when the Battle of Hastings brought William the Conqueror to England’s throne. Almost a century and a half later, June 19, 1215, became the signature day of the 13th century when King John signed the Magna Carta, enumerating the rights of free men and establishing the rule of law.

The D-Day moniker wasn’t invented for the Allied invasion. The same name had been attached to the date of every planned offensive of World War II. It was first coined during World War I, at the U.S. attack at the Battle of Saint-Mihiel, in France in 1918. The D was short for day. The expression literally meant “day-day” and signified the day of an attack. By the end of World War II, however, the phrase had become synonymous with a single date: June 6, 1944.

By the spring of 1944, as Daniel Levy and John Keegan have explained for us in eloquent detail, World War II had been raging for five tortuous years. If D-Day—the greatest amphibious operation ever undertaken—failed, there would be no going back to the drawing board for the Allies. Regrouping and attempting another massive invasion of German-occupied France even a few months later in 1944 wasn’t an option. Historians must assume that if Operation Overlord had been a catastrophe, a major part of the Allied invasion force would have been destroyed, and it would have been no small task to rebuild it. The massive armada and matériel could not be replaced with the waving of a magic wand. There was not a second team on hand to step in and continue the job. In fact, the aspect of the Normandy invasion that sets it apart from all other operations in military history is that it had no backup plan. There was to be one throw of the dice against the German might. Before the attack, Supreme Allied Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower confided to General Omar Bradley, “this operation is not being planned with any alternatives.” Failure would also have meant that the chosen invasion site was forever compromised. There were already precious few suitable areas along the entire western European coast from Norway to southern France from which to choose an invasion site. After a long vetting process, the Allies finally settled on Normandy.

They did this even though the targeted areas had more negatives than positives overall. The curious topography of the Normandy beaches was anything but ideal for the landing of a naval craft that needed to drop bow ramps into the churning surf. The area was subject to the third-largest tidal fluctuations in the world, making amphibious operations treacherous. None of the five selected invasion beaches were well enough connected to the others to allow mutual assistance when the going got extra tough. The planned landing was the equivalent of making five separate attacks instead of advancing on a continuous battle line. Defeat at any one of those Normandy beaches could spell doom for the largest seaborne assault in world history. “The Allies were invading a continent where the enemy had immense capabilities for reinforcement and counterattack, not a small island cut off by sea power from sources of supply,” U.S. naval historian Samuel Eliot Morison wrote. “Even a complete pulverizing of the Atlantic Wall at Omaha would have availed nothing if the German command had been given twenty-four hours’ notice to move up reserves for counterattack. We had to accept the risk of heavy casualties on the beaches to prevent far heavier ones on the plateau and among the hedgerows.”

There was no deep-water port to support this massive operation. It was one thing to put Allied troops ashore on a hostile beach, but keeping them there was quite another story. The supply requirements for food and ammunition were immense. To gain a foothold, the invading Allied army would require 400 tons of supplies each day to support just one infantry division, and a staggering 1,200 tons a day for each armored division. The initial assault was intended to have eight divisions land, but that was just the tip of the iceberg. The follow-up landings were to pour numerous other divisions ashore to form two armies.

And a landing at Normandy also meant that one of the great rivers of the world, the Seine, would be between the landing area and the objective—this being the industrial Rhine-Ruhr region leading into Nazi Germany. Rivers have proven to be great obstacles in military campaigns. A large, swollen river like the Seine would offer enemy defenders the opportunity to develop formidable lines.

Given all of these caveats, it’s fair to wonder why Normandy was such an attractive location to President Roosevelt, Winston Churchill and the other Allied planners. The most convincing argument in the region’s favor was its proximity to the supporting Allied airfields in southern England. A second advantage, ironically enough, was Normandy’s perceived unsuitability as a landing site. Since it was fraught with clear disadvantages, it was deemed the least likely spot in the German mind and therefore afforded the Allies an opportunity for surprise. Surprise was absolutely essential for Operation Overlord’s success because the Germans controlled the interior lines of communications and could quickly react to any threat by rushing reinforcements from far-flung locations in occupied France.

In 1944 the common appreciation for an amphibious assault had been graphically displayed in newsreel film as American audiences watched U.S. Marine assaults on flyspeck islands in the central Pacific. Waves of landing craft broke upon the hostile beaches to initiate furious attacks against isolated Japanese defenders. The enemy rarely had air or naval support. The scenario became very familiar: Land the landing force; cut the island in half by driving to the other side; clear the first half and then clear the second half and, in the process, annihilate the defenders or drive them into the sea. It would all be over in days or weeks. Speed was of the essence.

But an amphibious landing at Normandy would be far different from landing on a tiny island like Wake or Iwo Jima in the central Pacific. This was the European continent, and the defenders were hardly isolated or lacking in reserves. In fact, the Third Reich had the ability to call upon up to 50 divisions in the vicinity of Normandy to react to an Allied attack.

An attack on the Normandy beaches can best be described as a showdown. Those beaches in northern France were the gates to the fortress, and if it was successful, then the entrance into the Continent would allow the military and industrial might of the Allies to pour onto the battlefield. That overwhelming might could then make victory a reasonable outcome. But if the attack failed, the consequences for democracy would be dire. The threat to Germany from the west would be over. Adolf Hitler would not have to fight on two fronts. Allied long-range air attacks against Germany would remain just that—long range—and Hitler’s aircraft and rocket development could continue (as could the machinery of the Final Solution).

And what about the Soviet Union? Premier Joseph Stalin had made it clear that he had no intention of absorbing the losses and bloodletting of the war so that the Anglo-American alliance might come in at the end to reap the rewards. When Secretary of State Cordell Hull reminded his Soviet counterpart that the United States had not been unbloodied and indeed had suffered 200,000 casualties during the war, the Soviet diplomat abruptly cut him off, saying, “We lose that many each day before lunch.” And didn’t Russia bow out of World War I? What was to preclude another retreat and the conclusion of a separate understanding with Germany if it was advantageous to the Soviet Union? It had made deals with the devil before.

Exhausted from years of war, Europeans in 1944 longed for the day when they would be liberated from the totalitarian grip of Germany. There seemed to be no end in sight, and Great Britain had nearly depleted its reserves of manpower. It had fought alone in the Battle of Britain and had endured the naval Battle of the Atlantic. It had fought in Norway, North Africa and Sicily. It was now fighting in Italy and in the Pacific. On December 11, 1941, Adolf Hitler’s sudden declaration of war against the United States brought Britain the hope of salvation. But while there was guarded jubilation among the beleaguered British, American involvement in the war initially changed little. In two years of indecisive Allied operations against the Wehrmacht, the Anglo-American team had been able to attack only the fringes of the German Reich. The main Allied success, as we have seen in these pages, had been taking control of North Africa.

Everyone, including Winston Churchill, knew that the road to the end of the war ran through Berlin. But no one was marching to Berlin without first invading the Continent. The incorrigible Churchill declared, “Unless we can go and land and fight Hitler and beat his forces on land, we shall never win this war.”

On the other side, Hitler was equally astute concerning the inevitable Allied invasion attempt and the importance of defeating it: “Once defeated, the enemy will never again try to invade . . . They would need months to organize a fresh attempt.”

Any Allied entry into Europe was going to be possible only by breaching the western wall of what had aptly been dubbed “Fortress Europe.” In that respect, the Germans seemed to have all the military advantages. But the one advantage the Third Reich did not possess was superior intelligence capabilities. They were clueless as to where the invasion would come and could only speculate about potential landing sites. The Germans thought Calais the obvious landing point and made its beaches impregnable. Calais was situated less than 25 miles from the white cliffs of Dover across the English Channel, while the beaches of Normandy were 100 miles away.

The Germans had ignored Normandy, except for some basic defenses. Who would ever plan to land there? And if an attack were to come, how would it be supported without a port? General Dwight D. Eisenhower and his Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) team were encouraged to see only minor German defensive activity all along the windswept Norman coast. Nonetheless, the only chance for the operation’s success was to keep everything top secret. Eisenhower had succeeded in his role as Allied commander by remaining tight-lipped. If he hadn’t carefully cultivated a culture of trust between Americans and Britons, then Operation Overlord would have been doomed before it even began.

But “leak proofing” is easier said than done, especially when it comes to the “when” and “where” of a massive invasion like D-Day. The enemy is usually tipped off by invasion preparations—the most obvious being the use of aerial bombing and naval gunfire to soften up the site. Eisenhower decided that secrecy trumped softening, so the days and weeks preceding the landings were marked by silence instead of preinvasion bombardment.

The Great Secret would also be safeguarded by the unleashing of a monumental Allied deception plan, designed to convince the Germans that the invasion would occur at a location other than Normandy. Part of that deception included the efforts of 28 middle-aged British -officers, who settled in to a castle in the far reaches of Scotland with radios and operators. They planted fear in the German mind of the existence of a massive 250,000-man force: the British Fourth Army, which was capable of invading Norway. Their phony network traffic—purposely communicated in a low-level cipher that they knew the listening Germans could easily break—included requests for cold-weather gear and equipment.

If the D-Day invasion was to have a chance to succeed, the Germans would have to be continually misled. Churchill had told FDR that in wartime “Truth is so precious that she must often be attended by a bodyguard of lies.”

That bodyguard of lies led to the creation of many bizarre operations, not the least of which was the creation of a second, semifictitious Army group stationed in and around Dover. It was commanded by General George S. Patton, whom the German military leadership considered the best Allied combat leader. Wherever Patton was stationed, the Germans believed, the big invasion would surely follow. That meant they thought the cross-Channel attack would take place from Dover to Calais. At Dover, fake camps were constructed and tents erected to create the illusion that American soldiers were occupying them. Loudspeakers transmitted the recorded sounds of vehicles, tanks and camp activities that escaped through the trees and were heard in the surrounding towns. Guards were posted at the entrances and vehicles regularly moved in and out, but few people were actually actively engaged inside those gates.

Contributing to the deception were a whole host of agents and double agents all tasked to obscure and confuse. One such agent was the master of deception Juan Pujol Garcia, a Spaniard who assumed the code name Garbo. Posing as a German agent, he had created his own fictitious spy network of 20 operatives who supposedly fed him information about the Allies. Much of it was tantalizing and laced with elements of truth, but he passed it on to the Germans in such a fashion as to cause minimal damage to the Allied cause. Yet his accuracy was astounding to the Germans, and as a result he built impressive bona fides with the Abwehr (the German military intelligence). One of the many results of the deception plan was convincing Hitler that the Allies had 89 divisions when, in fact, they had only 47.

But despite all of the cloak-and-dagger work, Eisenhower still had to get the invading force ashore. That was no easy task at Normandy. Unlike other landing areas, Normandy has an enormous tidal wash that, twice a day, floods the beaches and then recedes. The 20-foot difference in elevation between low tide and high means that at high tide the water is 300 yards farther inland than at low. At high tide, the water covered the beach and the German obstacles and lapped at the wall.

Eisenhower planned to land at dead low tide, on five isolated beaches across a 60-mile front. Four of the beaches—Omaha, Gold, Juno and Sword—were enclaves along the Norman coast. The fifth was figuratively out on the end of a limb, alone on the Cotentin Peninsula, 15 miles south of Cherbourg. It was named Utah Beach and, while a successful landing there would position the attackers to make a run to seize the deep-water port of Cherbourg, Allies who landed there would be the most vulnerable. Their only protection from an annihilating German counterattack would be if the two American airborne divisions, the 82nd and 101st, could drop and seize the narrow causeways that led to the beach across flooded fields.

Eisenhower was also faced with having to move the entire armada across the widest part of the English Channel, thereby increasing its possible discovery. He had to isolate the battlefield where he intended to land. He was confident that his force could deal with any military forces already within the confines of the battlefield, but it was imperative to keep reserves and reinforcements from entering into the fray, especially during the early hours of invasion, when the attack was still feeble. To do that he called upon the air forces to disrupt and destroy the German ability to move. The British Royal Air Force and the United States Army Air Corps would bomb and attack bridges, railcars, rolling stock, train yards and tracks—-essentially any target that could be used to transport German reserves to the battlefield. Eisenhower labeled this simply the Transportation Plan.

But here, he ran into a thorny problem—not from the enemy, but from his own British and American air officers. They contended that the execution of the air offensive should be left to them and that bombing transportation targets would greatly impair their ongoing Oil Plan. They believed that if oil supplies, refineries and storage facilities could be annihilated, then the German war machine would grind to a halt. Unlike Eisenhower, they didn’t place transportation infrastructure high on the list of priority targets.

But Ike knew that the Transportation Plan would result in only a temporary halt of the Oil Plan. As Supreme Commander, he scoffed at the idea that he was not in charge of making determinations about the air forces. The air chiefs, however, did not share this belief and interpreted Eisenhower’s duties and responsibilities as limited to command on the ground and at sea. Even Churchill sided with the air chiefs concerning the Oil Plan, but as the crisis mounted, it was Eisenhower who brought the argument to an abrupt halt. As Supreme Commander, he was ultimately responsible for the success or failure of the operation. Unless he was given control of the bombers to use as he saw fit to accomplish his mission, take care of his men and win at Normandy, he would “simply have to go home.”

He won the argument. He unleashed the Transportation Plan on the Wehrmacht and, in the run-up to D-Day, destroyed 900 locomotives, more than 16,000 railcars and countless miles of track. The Oil Plan was later resumed with enormous success.

Solving the problem of the lack of a deep-water port was more daunting. Such existing ports were at Cherbourg, Dieppe and Calais and were heavily defended. A failed August 1942 raid on the small French port of Dieppe had proven just how well defended. The attack was a calamity for the Allies that resulted in more than 4,000 Canadian casualties. Nazi newspapers had cheered about Hitler’s forces decisively beating a huge invasion attempt.

The final answer to the port problem came in the form of an engineering marvel code-named Mulberry. Never before had an army tried to take its harbors with it to an invasion beach. A large consortium of British engineering companies tackled the problem of building two floating artificial harbors, each of which would have the unloading capacity of the Port of Dover. That port had taken seven years to build, but these floating ports had to be ready in 150 days. If the invasion proved successful, various parts of the Mulberry harbors would be towed across the English Channel to Normandy, where they would be assembled to make the two giant seaports.

The window of opportunity to launch this enormous attack was indeed a narrow one. There were four prerequisites. First was the tide. Eisenhower wanted to land on a late spring or early summer morning so he could use the night to conceal his seaborne approach to the Norman coast (and obscure his unloading operations). An early dawn landing offered some promise of surprise, and it would give him a full day of fighting to secure a foothold in France. The second consideration was the moon. The navy needed some light to maneuver the massive armada at sea, and the paratroopers would need at least some moonlight to allow them to find each other on the ground in the fields of France. The bombardiers also needed light to see and identify their targets.

The third and fourth prerequisites had to do with training. The 1944 landing would have to come early enough in the summer to allow a minimum of three months of good campaigning weather before the onset of winter, but it had to be late enough in the year to allow for the completion of training and, as we have learned, the construction of enough landing vessels, particularly the LSTs (Landing Ship, Tank). LSTs—what one officer described as “a large, empty, self-propelled box”—were the linchpins of D-Day. There were well over 40 different types of these landing craft used in the invasion.

Those four major restrictions left only a few options in all of 1944 for possible invasion days. The first opportunity would be on May 1, followed by a few days during the first and third weeks in June. The Allies had set May 1 as D-Day, but immediately had to cancel when it became evident that the invasion was short 271 LSTs. Hopefully one month’s delay would allow for the production of those additional ships. Churchill reportedly growled that the destinies of the “two greatest empires seemed to be tied up in some goddamn thing called LSTs.” But Eisenhower set D-Day back to June 5 to have more of the vessels at his disposal.

The month of May brought gorgeous weather to Normandy. General Eisenhower was encouraged and moved his headquarters from London to Southwick House, near Portsmouth. Upon arrival, he sent a coded message to all his chief commanders: “Exercise Hornpipe plus six.” That meant that June 5 was still confirmed as D-Day. He sent a second message to Washington: “Halcion plus 4,” meaning precisely the same thing.

But as fate would have it, almost as soon as Eisenhower sent those encouraging missives, signals arrived from American planes flying weather missions over Newfoundland. They showed that conditions were drastically changing off the East Coast of the United States. A great swirling front was developing, and this disruptive weather system was labeled “L5.”

By June 3, though the weather was beautiful over the English Channel, L5 was becoming a major problem. The chief of SHAEF’s meteorological team, Group Captain James M. Stagg of the British Royal Air Force, followed its trajectory and then alerted Eisenhower that the weather prospects were not good. In fact, there was a possibility of Force 5 winds on June 4 and 5. Stagg reported that the whole North Atlantic was filled with a succession of depressions of a severe nature theretofore unrecorded in more than 40 years of modern meteorological research. He recommended postponing the operation.

A disappointed Eisenhower grilled Stagg and made a reluctant, provisional decision to postpone D-Day. His final decision would be made after the 4:15 meeting on the morning of June 4. The 6,000 ships of the invasion force were all in position, with the soldiers having been embarked for several days. Some vessels had even started the long crossing. The cross-Channel attack was like a drawn bowstring, straining for release, and L5 was in the way.

By 4:15, nothing had changed. At the meeting, Eisenhower polled his staff. Some bullheaded advisers wanted to go full throttle to Normandy, bad weather be damned. Others did not. The Allied Navy, under the command of Admiral Bertram Ramsay, said it would be unaffected by high winds and chop. But the planes would have a major problem, especially the troop carriers in charge of delivering the paratroopers. Without the paratroopers protecting the approaches to Utah Beach, that landing would have to be called off. Eisenhower postponed D-Day until June 6. The great armada, already at sea, was called back. The paratroopers were stood down for 24 hours, and Eisenhower and his staff would again meet at 21:30.

At 21:30, Stagg’s predicted gale-force winds were driving the pouring rain horizontally into the windowpanes of Southwick House, the estate that served as the site of SHAEF’s Advance Command Post. As Stagg entered the tension-filled room, he surprisingly modified his gloomy predictions and reported that despite the present stormy weather, the cloud conditions would improve and the winds would lessen after midnight. The weather would be tolerable, but no better than that.

Again Eisenhower polled his lieutenants, who were still divided. He finally declared, “I’m quite positive the order must be given . . . I don’t like it, but there it is.” Operation Overlord slipped back into gear, and the great armada rolled out into the English Channel. On June 5, Eisenhower left himself one last opportunity to recall the invasion at an early morning meeting scheduled for six hours later. At that 4:15 gathering, nothing had changed. Eisenhower gave the final order in three brisk words: “Okay, let’s go.”

In the end, the weather didn’t terribly disrupt the D-Day landings, and the blustery conditions lulled the Nazi defenders into thinking that an Allied attack was impossible. The invasion began on the wings of the airborne assault and its 21,100 paratroopers. On the eastern edge of the invasion area, the British 6th Airborne Division came in to seize and control key bridges to keep any German counterattack from striking the flank at Sword Beach and rolling up the invasion. On the west side of the battlefield, the American airborne dropped in to seize the towns of Carentan and Sainte-Mère-Église in order to control the road networks leading to Utah Beach.

The American sky train that flew to Normandy comprised 850 troop carriers. They flew in a formation nine planes wide and 300 miles long. It took great skill to avoid midair collisions, and radio silence was strictly maintained. A tiny blue dot on the tail of each aircraft was all that a pilot could see of the plane to his front. British air marshal Trafford Leigh-Mallory had confided to Eisenhower that he thought up to 70 percent of the paratroopers could be killed, wounded or captured.

Eisenhower had joined these paratroopers at their airfields and remained until the last C-47s had disappeared into the night before retiring to his small trailer near Southwick House. He penned a note to be released if the invasion failed: “Our landings . . . have failed. And I have withdrawn the troops. My decision to attack at this time and place was based on the best information available. The troops, the air and the Navy did all that bravery and devotion to duty could do. If any blame attaches to the attempt it is mine alone.”

The great sky train flew to the west of the Cotentin Peninsula and then turned to the east to cut across the narrow neck of land. Its approach was greeted by a heavy German antiaircraft barrage. Many men described the colorful display of tracers streaming up through the night as if they were Roman candles. When the flak struck the aircraft, it sounded like nails being thrown against the sides. The intense fire caused many aircraft to swerve to avoid midair collisions and others to increase their speeds to escape the streams of green and yellow fingers reaching into the sky.

The air over France was filled with parachuting soldiers. It was also filled with falling debris—burning aircraft, detached rifles, helmets and packs ripped from the troopers by the impact of their parachutes opening. The drop was badly scattered, and paratroopers landed in trees, hedgerows, farm fields and on barns. Very few landed in their designated zones, but they were able to adapt thanks to their training and discipline. Some troopers joined other units and fought until they could find their own squads and platoons. Others attacked the Germans wherever they could find them. They all struggled to seize the causeways and gain control of the roads.

At two a.m. on June 6, the ships of the great armada halted 12 miles off the Normandy coast and began disembarking their soldiers into landing craft. The gigantic fleet had crossed the English Channel undetected and, by three o’clock, the small landing craft were already circling, awaiting their run to the beach. Then and only then came the prebombardment of the invasion area. There was one hour of battleship and heavy-ship naval gunfire, followed by one hour of a 2,000-plane bombing offensive.

The landing craft finally began their run-in to the five invasion beaches. Because of the diagonal direction of the incoming tide, the American beaches were assaulted at 6:30, one hour before the British beaches to the east. The American 4th Infantry Division landed at Utah Beach with its armor in the lead to easily sweep aside the small German defending force. The infantry came in next and moved off the beach. By noon they had linked up with the elements of the 101st Airborne that had earlier sealed off the approaches to the beach. The landings at Utah succeeded beyond the wildest expectations of the Allied planners; the combined air and sea assault had worked perfectly despite the scattered paratroop drop. Leigh-Mallory’s prediction that 70 percent of the paratroopers could be lost was, thankfully, off the mark. There were many fewer casualties, and the landing had generally surprised the German sentries.

Thirty miles to the east of Utah Beach, the American assault regiments of the 1st and 29th Infantry Divisions approached Omaha Beach, which was dominated by a looming 100-foot cliff. It was at this location that Field Marshal Erwin Rommel had recognized this beach as a possible invasion site and ordered it fortified. For the next few months, the Germans had constructed concrete-and-steel defensive positions. There were 15 of these massively strong positions, called Widerstandsnests, covering the entire length of the six-mile beach, each bearing a number from 59 to 74.

Unlike at Utah Beach, the first wave to land at Omaha did so without armor. Only five of the 32 tanks assigned to the landing site made it to the beach, and those were immediately destroyed. The German fire along the beach was tremendous, especially from the Widerstandsnests, and the American line was broken. The Americans had run into a wall of steel, and camouflaged guns fired an enfilading crisscross pattern across the entire length of the beach. Twenty minutes later, there were few men who were not dead or wounded. And then, on their heels, came the second and third waves, each destined to meet the same fate.

The Americans were pinned down. Some hid behind beach obstacles. All along the beach, small groups attempted to crawl forward, knowing that salvation would be found off the beach. American officers ran up and down, yelling at the men to move out and telling them that the only way to survive was to get up to high ground. In twos and fours they crawled and clawed their way through barbed wire and mines to the sloping ground. With the help of direct fire from daring American destroyers, the Americans slowly pushed the Germans out of their positions. By 11 o’clock, the fire on the beach was diminished. A little after noon, the beach was mostly quiet.

But the effort to win at Omaha came at a tremendous cost. There were more than 2,000 casualties. The beach was strewn with wrecked vehicles and burning ships and boats. Some infantry units had lost most of their officers and many of their soldiers. The fight on that beach earned the name Bloody Omaha.

In the center of the invasion area, just four miles west of Omaha Beach, was a strange and dangerous place called Pointe du Hoc. It was a point of land that stuck out into the English Channel and rose 100 feet above the water between Omaha and Utah beaches. The Germans had fortified this promontory with large, 150mm guns that were able to fire on both beaches and therefore threaten the entire invasion. Eisenhower knew that this fortification had to be taken and ordered the Rangers of the 2nd and 5th Battalions to eliminate the threat. Unlike at the beaches, Pointe du Hoc had no shoreline. The Rangers would have to scale the steep cliffs to attack the guns.

“When we went into battle after all this training there was no shaking of the knees or weeping or praying,” U.S. lieutenant James Eikner of Mississippi recalled. “We knew what we were getting into. We knew every one of us had volunteered for extra hazardous duty. We went into battle confident . . . We were intent on getting the job done. We were actually looking forward to accomplishing our mission.” No matter how many oral histories are collected about D-Day, it’s still impossible to understand what each man felt as he crossed the English Channel. There was not a singular kind of war experience for the survivors of that day.

Arriving in eight landing craft, the Rangers fired hooks and grapnels with attached ropes from mortar tubes on the boats. When they snagged on the barbed wire or the ground on top of the cliff, the Rangers began to climb, hand over hand. Once at the top, they attacked the surprised Germans, swept them aside and rushed to the fortifications to silence the guns. But the concrete casements had no guns. In their place were protruding telephone poles disguised to look like guns in order to deceive aerial photography.

The Rangers secured the position and moved inland to block the coastal road that ran behind all the invasion beaches. But two Rangers reconnoitered a dirt path that ran between the hedgerows separating the farm fields. A short distance down the road, they found real guns, well hidden under camouflage netting and aimed at Utah Beach. The Germans had no idea that there were any Americans within miles of their position, and while the gun crews were at the far end of the field listening to a German -officer -issuing orders, the Rangers squeezed through the hedges and disabled the guns with thermite grenades before creeping out. The guns were eliminated. Though the Germans furiously counterattacked the -Rang-ers for the next two days, the Rangers held on. Those five German guns, capable of wreaking havoc on the invasion force, remained silent on D-Day.

Farther to the east, the Canadian 3rd Division approached Juno Beach. But because of buffeting currents and difficult navigation, their landing craft arrived after the rising tide had covered many of the beach obstacles. The boats began to strike these obstacles, which were called tetrahedrons, hedgehogs and Belgian gates. Great pilings had been anchored in the sand with mines attached to the tips. As the boats snagged on them or had their bottoms ripped out or exploded, the vessels sank, taking their embarked soldiers with them. Whole boat teams were lost in the surf of Juno Beach.

From the land, German defenders fired on the boats that managed to avoid the mines, until some of the Canadian soldiers finally landed and were able to push through the shallow German defenses. But half of their boats had been damaged, and more than a third forever lost. By late morning, the Canadian division had gained control of the beach, but at a cost of more than 1,000 men.

The British landings at Sword and Gold beaches were huge successes. The British 3rd and 50th Divisions made great progress and moved aggressively inland from their beaches. By two o’clock, elements of the British amphibious forces from Sword had linked up with the 6th Airborne, which was protecting the east flank of the invasion area. The forces at Gold Beach achieved most of their objectives and were the only unit to link up with an adjacent beach when they joined forces with the Canadians on Juno. “D-Day was a success, and the Allies had breached Hitler’s seawall,” President Ronald Reagan noted on the 38th anniversary of the Normandy invasion. “They swept into Europe, liberating towns and cities and countrysides until the Axis powers were finally crushed. We remember D-Day because the French, British, Canadians and Americans fought shoulder to shoulder for democracy and freedom—and won.”

As D-Day ended, the Allies were far short of the grand objectives that had been optimistically set for the day. The old aphorism that “no plan survives first contact with the enemy” held true. But the Allies were dug in all across the front, and the German army had not been able to hurl them back into the sea. These young soldiers didn’t know that they still faced seven weeks of hard fighting before the Normandy campaign would be won. But in those next seven weeks, through newsreels and photography, the world followed them through the shattered French villages, first to capture Cherbourg and finally to break out of Normandy at Saint-Lô. You see that imagery on these pages. Cameras captured Allied forces as they were greeted every step of the way by the suddenly free French people.

A young French girl who had sought to help the wounded on Sword Beach that D-Day morning saw the war’s end in sight. To her, D-Day was the moment when -liberty was reclaimed for the world. She said, “When I saw the invasion fleet, it was something that you just can’t imagine. It was boats, boats, boats and boats at the end, boats at the back, and the planes coming over. If I had been a German, I would have looked at this, put my arms down, and said, ‘That’s it. Finished!’”

Douglas Brinkley is a professor of history at Rice University and author of The Boys of Pointe du Hoc: Ronald Reagan, D-Day, and the U.S. Army 2nd Ranger Battalion and Voices of Valor: D-Day, June 6, 1944 (with Ronald J. Drez).

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com