There’s a widespread belief within the community of professional photographers that amateurs, armed with cheap camera phones and DSLRs and supported by new media organizations and social sharing communities, have become full-fledged economic rivals.

It’s no secret that journalism is a sector in crisis – dwindling advertising budgets coupled with a deep-seated reluctance from media actors to evolve in the face of change have led many organizations to seek alternative ways to sustain their operations. But is the amateur photographer to blame?

On July 7, 2005, when four British Islamists detonated bombs aboard three of London’s underground trains and one double-decker bus, commuters Adam Stacey and Alexander Chadwick used their camera phones to shoot images from the darkness of the city’s tunnels, which journalists couldn’t reach. Their photographs ended up on television and, in some cases, on the front pages of international publications including the New York Times and the Washington Post.

Two months later, the French newspaper Liberation raised the alarm, asking: “Are we all journalists?” It accused amateurs of trivializing and privatizing the news, with journalists left to wonder “whether the scaremongers who predicted the end of the media had been right all along.”

For Samuel Bollendorff, a French photographer and documentary filmmaker, amateurs are just scapegoats for a profession that has refused to accept its share of responsibility in its economic struggles. “My role as a photographer, at least the way I see it, is to try to understand how people around me produce, distribute and consume images,” he tells TIME. “For the past few years, we’ve heard the worse things about amateurs, which are accused of having brought photojournalists to their knees. I thought it was important to take a look back at these claims and uncover these amateur images that have made the front pages over the years.”

Bollendorff’s survey, which he put together with Andre Gunthert, an associate professor at the French School for Advanced Studies in Social Sciences, has gone on show this week at the Visa pour l’Image photojournalism festival in Perpignan, France.

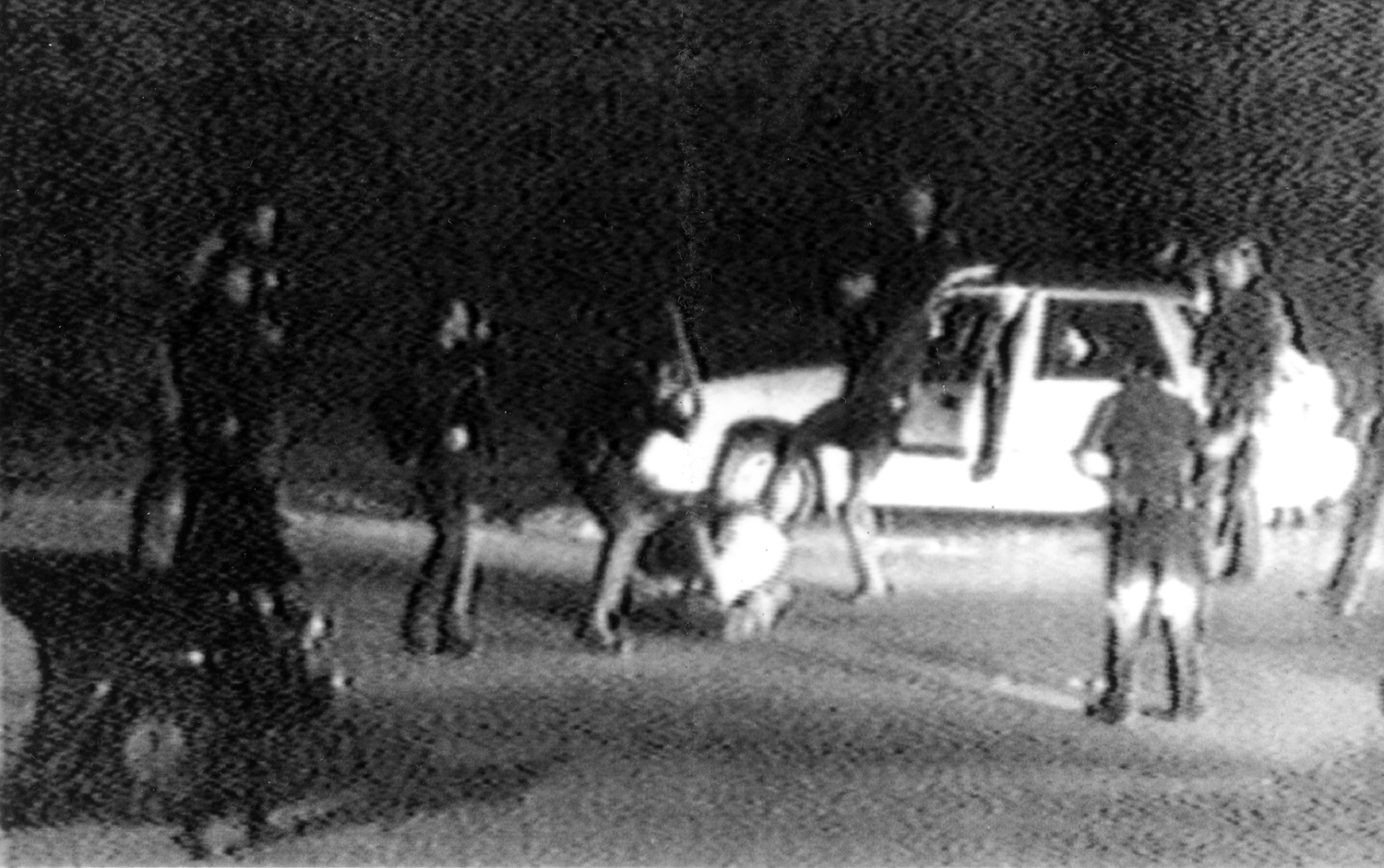

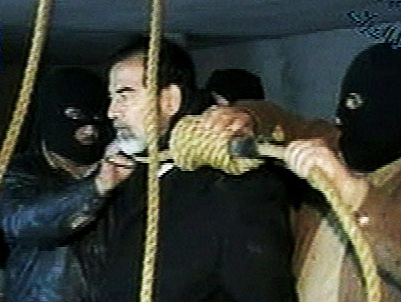

The exhibition includes images of John F. Kennedy’s assassination, Rodney King’s beating, abuses at the Abu Ghraib, Saddam Hussein’s hanging and of the March 2011 tsunami in Japan, among many other events. “When we brought these images together, we quickly realized that, within the past 15 years, it was hard to find 30 images that had a worldwide impact,” notes Bollendorff.

These images, Gunthert argues, might have made the front pages, but they didn’t lead to a change in the way newspapers use imagery. “If you look at the media today, they’re not covered in amateur images,” he tells TIME. “On the contrary, we’re still seeing a large majority of professional images.” In fact, he adds, most start-ups whose business model has been to sell amateur images to newspapers have, so far, failed to grab significant market share from established image agencies.

For Bollendorff this could be explained by the fact that most amateur “images” are actually stills that have been extracted from video files. “I find it interesting that photographing comes naturally to photographers, but amateurs have a tendency to make videos. Then, the journalist comes in, seeks that witness, gets the video and edits it down to one image.”

This was particularly evident when Libyan rebels filmed, using their camera phones, a captured Muammar Gaddafi being beaten and stabbed to death. “Photographers and journalists only arrived on the scene later on, and they could only collect these amateurs videos – some of them even taking photos of these videos playing on the rebels’ phones,” Bollendorff says.

For Visa pour l’Image’s director Jean-Francois Leroy, this retrospective is proof that “it’s become more difficult for professional photographers to be the first witnesses of an event.” Instead, the challenge is to produce images that will contextualize that particular event and add more layers to the initial photograph.

Bollendorff hopes his show, which will travel to Paris in November, will bring an end to photojournalists’ propensities to blame amateurs for the current state of the market. “Yes, there’s a real crisis within our industry, but it’s due to the fact that media organizations now belong to large conglomerates where profitability is important. It’s an internal problem, but it has nothing to do with amateur images.”

Amateurs Make the Front Page is on show at the Visa pour l’Image photojournalism festival in Perpignan, France until 14 September.

Olivier Laurent is the editor of TIME LightBox. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram @olivierclaurent

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com