The Great Pumpkin Race

Topsfield, Mass.— A voice has long whispered in American ears: Bigger, it says. So we get Manifest Destiny. And the Empire State Building. And the McMansion and the Humvee and the concept of “Texas-sized” too.

This also brings us the 1,900-lb. pumpkin sitting in a temperature-controlled glass pavilion at a fair 35 miles north of Boston in early October.

It’s a beast of a gourd: it looks wider around than an ox and tall as a Great Dane, with a stem as thick as a human thigh, its burnished peach-colored skin reflecting the glare of camera flashes as admirers pose for selfies with it. For growing this pumpkin, 74-year old Hiram Watson of Farmington, N.H., won the annual Topsfield Fair weigh-off and took home $5,500.

A century ago, Watson’s pumpkin would have been an unthinkable feat of agricultural prowess. Even 30 years ago, when the Topsfield weigh-off debuted, the winner was a measly 433 lbs. On a warm fall day, the line to see the pumpkin inches forward slowly. Toddlers press cider-sticky fingers to the glass in awe. Grown-ups circle it appraisingly. The magic number, nineteen hundred, is heard on every tongue.

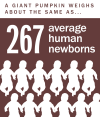

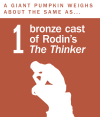

But Watson’s pumpkin, though impressive, is not even a record-breaker. Today, a pumpkin has to pass the ton mark to be noteworthy. That’s about the weight of a full-grown walrus, heavier than a Smart car, more than three times the Olympic weightlifting record in the clean-and-jerk. This is not a matter of a few pounds added to the record each year. Though it took about a century to get competitive pumpkin growing from its starting point — a 400-pounder at the 1900 Paris World’s Fair — to the thousand-pound mark, it took a mere 16 years to gain another thousand. Every year since 2008 has set a new world record. Numbers that once seemed impossible are now bandied about by the most serious competitors.

“I hope I can see 3,000. Maybe 3,500. Heck, we might have the first two-ton pumpkin out there. It could happen,” says Dave Stelts, 55, who is president of the Great Pumpkin Commonwealth, an organization he describes as “basically the Olympic Organizing Committee of competitive vegetable growing” and “the Good Housekeeping Seal of weigh-off sites.” Official GPC weigh-offs see a few thousand pumpkins a year, but Stelts estimates there are 10,000 total growers out there, waiting for the fairy godmother of gardening to turn their pumpkins into glory.

In 1979, a Nova Scotia farmer named Howard Dill happened to grow a particularly large pumpkin. He decided to bring it to a fair near Philadelphia that was holding a weigh-off; his 438.5-pound vegetable — a Lilliputian to today’s Gulliverian gourds — won first place. His son, Danny, 50, who now runs the family farm, recalls that his father felt crazy to leave the farm just to show off a big pumpkin. But in 1980 his pumpkins were even bigger. And in 1981 it happened again, clearly no fluke. There was something special about the seed. He called the strain Dill’s Atlantic Giant.

That was the start of modern competitive pumpkin growing. After all, seeds are the heart of the pumpkin game. And you don’t need to be a farmer to understand how it works; you only need to know where babies come from.

So, a quick refresher on vegetable reproduction: pumpkins, like puppies and people, come with either male or female reproductive organs. Before the pumpkin itself, the plant bears flowers. Male flowers have a stamen with pollen on it and others have a small bulge — the beginnings of a pumpkin, the analog of an egg — under a stigma that can catch the pollen. In order for the pumpkin to grow, the pollen from the male flower has to get into the female flower. Rather than depend on bees, competitive growers pollinate by hand to make sure to use both seeds and pollen from plants with proven genetic lines. When the GPC lists its standings, pumpkins are identified by their parents; for example, last year’s record-breaker was a 2,032-pounder grown by Tim Mathison of Napa, Calif., with the “father” plant grown from a seed of “1554 Mathison” (a 1,554 pounder from Mathison’s own stock) and a “mother” seed from the plant known as “2009 Wallace.”

And “2009 Wallace” is no ordinary pumpkin. “2009 Wallace” was the first-ever pumpkin to cross the ton barrier, grown in 2012 by Ron Wallace of Greene, R.I. Wallace recalls that when the first 1,000-lb. pumpkin was weighed many in the sport thought they’d peaked. He wasn’t satisfied. “Now my goal is 2,500 lbs.,” he says. “People say it’s impossible. People say it can’t be done.”

There’s no reason not to try. After all, every pumpkin produces hundreds of seeds. The children of “2009 Wallace” are legion; Hiram Watson’s pumpkin is its grandbaby. Every pumpkin growing season is another generation, a chance to select the seeds from the biggest pumpkins and pollinate them with other big-pumpkin plants and thus grow an even bigger pumpkin. Properties like color and taste fall away. For size and sturdiness, however, the growers are exacting. “Pumpkin seeds, they’re like breeding horses,” Wallace says. “When you finally get that race horse, the genetics are there.”

The nature versus nurture question has invaded the backyard garden as well. Wallace estimates that he spends up to 40 hours a week and thousands of dollars a year ushering seeds to greatness. (Though prize money for a big pumpkin also can be in the thousands of dollars, there’s no living to be made in the hobby.) Some growers talk to their plants. Others water with milk, which they claim provides important calcium. The more scientific-minded among them, like Wallace, swear by an organic soil-enhancer called mycorrhizal fungi. They send soil and tissue samples to a lab to make sure the pumpkins are not short on any nutrients.

But the seeds have been there all along, carrying the genetic code for enormity. The passionate growers have too. What made the difference — as with so many things — was the Internet.

When many of today’s big growers got their start, the best resource for beginner growers was word of mouth and, later, a book called How to Grow World-Class Giant Pumpkins, by Don Langevin, which came out in 1993. If you heard about a particularly big pumpkin, you wrote a letter to the grower and asked him to send you a seed. He might respond, or he might not. All that waiting and wondering is now a thing of the past. “I’ll get a [Facebook] friend request one day,” says Joe Pukos, 61, a grower from near Rochester, N.Y., “and the next day they’ll ask for seeds.”

The best seeds spread around the world, freely given or purchased, occasionally for exorbitant amounts, in auctions that raise money for local pumpkin clubs. The Internet has also expanded the community element of pumpkin growing, allowing hobbyists to compare notes and chat in the off-season. There’s a yearly pumpkin convention. There’s even a cruise.

Yet even the deepest understanding of pumpkin genetics fails to address the most obvious question about the world of competitive growing. Sure, it’s possible to grow 2,000 lbs. of pumpkin. But why the heck would anyone want to?

Maybe it’s the prize money. Maybe it’s the pride and the bragging rights. Maybe it’s tradition. Ron Wallace and Dave Stelts and Danny Dill all followed their fathers into the garden. Tim Mathison, who took the world championship in 2013, is passing it on to the next generation. “My daughter loves it,” he says. “She’s pretty severely handicapped; we take her out to the garden every night. She cannot talk or walk but she takes part in what goes on out there.”

Maybe people just like pumpkins. “Have you ever heard anybody say a bad word about a pumpkin? No,” Wallace says. “Pumpkins could solve the world’s problems. Honestly, everybody loves a pumpkin, they do, and to see one grow that big.”

Could there be a limit to that growth? As weights increase, growers are beginning to confront the possibility that we may be approaching maximum-pumpkin. The physics alone are an issue. A pumpkin is disqualified from competition if it’s cracked and, because heavier pumpkins aren’t necessarily sturdier, the weight of the vegetable itself can ultimately be its end. An even bigger problem is that a pumpkin has only so long to grow. The seeds can’t go in the ground in most parts of the U.S. until April. Summer is peak growing season for the actual vegetable, during which they can put on dozens of pounds a day. Weigh-offs are in September and October. Even if the weather is perfect, you’re not going to get much more than a few months to make the magic happen. Grow too fast, however, and you risk cracking.

A scientist named John Taberna, at Western Laboratories in Parma, Idaho, has become something of a guru for pumpkin growers; his lab is the one to which Ron Wallace turns to monitor nutrient levels in his garden. Taberna was first contacted about analyzing pumpkin growth nearly two decades ago, and he says that growers laughed when he first said that a ton was possible. Today, asked his professional opinion on whether pumpkins can get bigger forever, he hedges his bets. “The genetic code is there for 2,500 lbs.,” he says — but, if a grower kept the plant in a greenhouse, started early and pumped in extra carbon dioxide, “we might hit a 3,000-pounder some day.”

Yet the growers plant on, undaunted. After all, even Taberna admits that the limitations on pumpkin size are merely practical. In theory, there wouldn’t have to be a maximum. Meanwhile, the activity is getting more popular outside North America, where it’s not just growing out geographically but growing up in size, perhaps due to greater reliance on greenhouses. The very weekend that Hiram Watson scored with 1,900 lbs., a grower named Beni Meier, in Switzerland, entered a 2,102-lb. pumpkin into the books, the first-ever non-North-American GPC record holder. About a week later, he topped his own world record with a massive 2,323 lbs. The weigh-off season still has a few weeks to go. Suddenly, the idea of 2,500 lbs. doesn’t seem so outlandish.

This world may be a hard one, full of war and suffering and a million other reasons to stop hoping — but it is not yet a world of people who don’t want to grow a bigger pumpkin.

“People want to push themselves, and it’s the same thing with us,” says Dave Stelts, the Great Pumpkin Commonwealth president. “It stops when we want it to stop, when we quit looking for ways to make them bigger. Until then, the sky’s the limit.”

Or perhaps, is the sky no limit at all? So far, when that voice has whispered bigger, the pumpkin has only ever complied.