Avedon’s Animal Side

When Richard Avedon was a young boy, his parents used to borrow dogs. The animals were cast in small, but essential roles in Avedon family portraits, used to create an image of who the middle-class family from Uptown Manhattan aspired to be. Dreams of unattainable affluence, signified by pet poodles. “We posed in front of expensive cars, homes that weren’t ours,” Avedon said years later. “It seemed a necessary fiction that the Avedons owned dogs.”

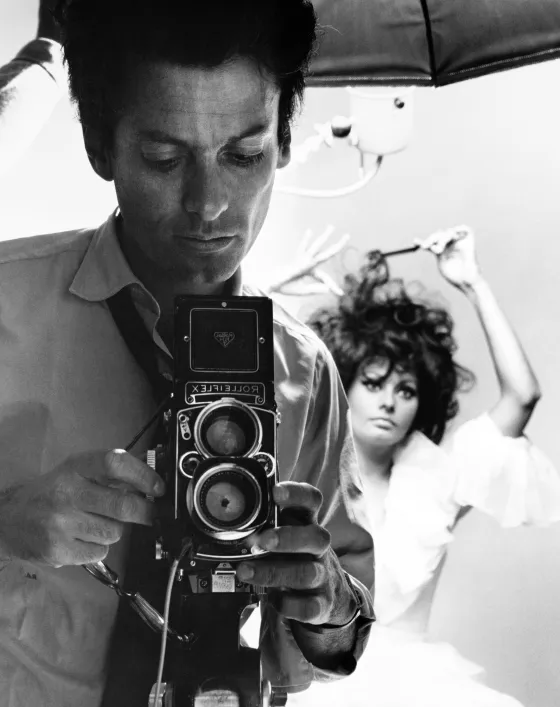

Avedon shaped America’s notion of culture and style for nearly 60 years, while his inventiveness produced some of the most iconic portraits of the last half-century. What united them all was a disregard for reality and a nod to the impossibility of truth. And animals often played a crucial role. From the mournful glare of the Duchess of Windsor – whom he provoked by pretending he ran over a dog en route to the shoot – to the inexplicable Bee Man, he always photographed with a heady coalescence of fact and fantasy. “Dick had a famous quote that he would say,” Sebastian Kim, Avedon’s former assistant, tells TIME. “’In an image, everything is a lie, none of it is truth.’ And surely he was the master of that.”

One early assay came in the 1950s, at the dawn of ready-to-wear fashion. “Avedon was one of the first photographers to take the model out of the studio and into real environments,” says James Martin, executive director of the Richard Avedon Foundation. “The pictures play with truth; the models are in ‘real’ situations, walking their dogs or sat in street cafes – but they’re wearing Dior and Chanel. The scenes are at once aspirational but unattainable. “Fashion is about who you want to be, not who you are,” Avedon once said in an interview. “It’s therefore artificial… it’s funny and it’s sad and it’s a little crazy. But I would want those elements to be in any photograph I took.”

“In an image, everything is a lie, none of it is truth.”

– Richard Avedon

Avedon expanded on this idea in 1955 with the madness of Dovima and the Elephants. This time, he took Haute Couture out of the studio and placed it in the elephant pen of the Paris Cirque. The tension between model and beast and the underlying beauty of the image is palpable and impossibly perfect. “Avedon did use animals to change the sense of the scenery,” says photo-historian and critic Vicki Goldberg. “Not only is Dovima and the Elephants arresting – and it does stop you on the page, there’s no question – but it is so unlikely that is becomes a fairy tale.”

Though he didn’t return to this dreamlike sequence again – he would have seen no point in that – he continued to use animals as props to similar effect. A collaboration with Egoiste magazine saw model Tatjana Patitiz photographed in graphic, grey shadow in a tank with a dolphin, while a shoot for Vogue saw a live snake wrap itself around Nastassja Kinski’s naked body; in both, animals elevate the picture to another realm. “Generally speaking the animals in his fashion photography are there to put a new spin on what is happening,” says Goldberg. “It’s half real and half not.”

Avedon was always searching and refining, molding and re-configuring. One of his seminal experiments came in the spring of 1969, when he brought his white seamless background to the Bronx Zoo to take portraits of birds for Harpers Bazaar. Though Avedon ultimately rejected them – they were never published until now – they seem to be the initial stages of Avedon trying to find a new visual vocabulary. “Just a few weeks after this failed attempt, Avedon makes his first portrait [of Renata Adler] in this new style,” says Martin. “All artifice and props, all romantic lighting is rejected. It’s the subject and Avedon interacting. These white background images with their black borders become synonymous with Avedon. He uses this technique for the rest of his life, and recreates himself and ultimately changes our understanding of portraiture.” The Bronx sitting was an adventure, a way for him to understand how he wished to photograph people.

Indeed, it was never really just about the animals. As Egoiste editor and long-time Avedon collaborator Nicole Wisniak says; “I think Dick had no interest in animals themselves but only in human beings.” They acted as subplots, foils or visionary devises; small but essential roles to further elevate Avedon’s world of elaborate fiction.

Richard Avedon (1923-2004) was an iconic portrait and fashion photographer from New York City. For more information on his life and work visit The Richard Avedon Foundation.

Alexandra Genova is a writer and contributor for TIME.com. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.