If interning were an Olympic event, Ivellisse Morales would be a gold medalist. Since her freshman year at Boston University, the 21-year-old public relations major has racked up seven internships. During the course of her odyssey, she has done everything from stuffing envelopes and running errands to writing analytical reports, all the while attending classes and working part time at an outside job. This summer, Morales crowned her vita with a plum internship: the communications desk of Teach for America in Manhattan.

Almost forgotten in all this résumé building, though, is the fact that in the thousands of hours Morales has spent working, her efforts have barely made a dent in the $55,000 in student loans that she has accumulated. Only four of the internships were paid, all but one providing no more than $12 an hour; a few granted minimal school credit. But Morales is surprisingly at peace with the way the nonremunerative internship game is played. Would-be employers, she says, “are not going to care how high your grades were. They’re going to care what you’ve done in the past.” Nonetheless, upon hearing about an unpaid 40-hr.-a-week summer internship in her field, she winces, admitting, “It’s slavery almost. Because they’re getting the same amount of work as a full-time employee but for free.”

Welcome to Interning 101. Internships, which used to be primarily for medical students, have become ubiquitous in the corporate, nonprofit and government worlds. Some are paid, albeit badly, but nearly half aren’t, according to a new report by the National Association of Colleges and Employers. Only 3% of undergraduates were interns in 1980; it is estimated now that of the 9.5 million students at four-year schools in the U.S., 1 million to 2 million have an internship in any given year, meaning that as many as 75% have had one by graduation. Further bolstered by companies looking to leverage cheap labor in an economic downturn, internships have become “the principal point of entry for young people into the white-collar world,” writes investigative journalist Ross Perlin, the author of the compelling Intern Nation: How to Earn Nothing and Learn Little in the Brave New Economy. With the youth unemployment rate at 17.4%, nearly twice as high as the adult rate, many college students are being driven to take unpaid jobs with the promise of paid employment that never materializes.

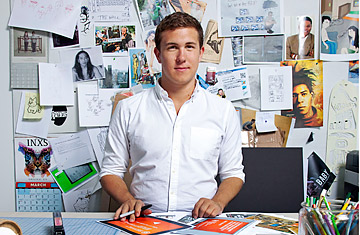

Consider the experience of Jordan Jacobson, 22, who graduated in May from the University of Kansas. The graphic-design major, who has five internships under his belt and upwards of $35,000 in student debt, was paid a paltry stipend of $300 a month this summer by a small design agency in New York City. “They told me they usually hire their interns when their internships are over,” Jacobson says. But partway through his stint, they blithely waved him away. “I think when they hired me, they knew very well that they wouldn’t be able to give me a full-time job. I was working pretty hard for them. I didn’t feel very good about it,” he admits. “I felt a little used.”

While Jacobson’s experience was unfortunate, according to Perlin, tens of thousands of internships are actually illegal. “A significant number of unpaid internships are a form of mass exploitation hidden in plain sight,” says Perlin. What’s wrong, he says, is that under U.S. labor law, “even if you don’t pay at least minimum wage, you have to run your internship as a bona fide training program.” Just having the student earn money for the company doesn’t make the grade, legally. But in May, Michael Hancock of the Wage and Hour Division of the U.S. Department of Labor, despite calling unpaid internships “a spreading cancer,” admitted that his agency didn’t have sufficient resources to police this “vexing problem.” Said Hancock ruefully: “It’s not at the top of our priority list.”

Companies, understandably, are not eager to talk about their unpaid-internship programs, though CBS News’ Sunday Morning recently discussed its arrangement on the air: 75 interns each make a stipend of $50 a week, which doesn’t even cover a week’s worth of sandwiches in midtown Manhattan. In the broadcast, ambivalent CBS interns expressed their unease about the arrangement, but Tracy Smith, the CBS correspondent for the segment, was seemingly unperturbed. “If the kid says, ‘I want to do it, I want the experience,’ what is wrong with that?” she asked an expert. Emotions aside, the hard truth is that it’s a buyer’s market–plenty of young people looking for work, particularly in glamorous professions like television, are prepared to toil for free. But anger over the issue is growing. When the Chronicle of Higher Education recently ran an op-ed titled “Internships Have Value, Whether or Not Students Are Paid,” readers pelted the article on the publication’s website. “About 150 years ago, we also had a system that ‘provided work experience’ for no pay,” wrote one reader, sarcastically comparing the practice to slavery.

All this merely underscores a larger economic trend in the U.S., which is the two-tiered job market–one in which class is increasingly playing an important role. “Corporations and institutions are turning regular paid jobs into internships, and the internships which had been paid are being converted into unpaid positions,” says Andrew Ross, a professor of social and cultural analysis at New York University. “Only the wealthiest can afford to put their foot in the door, which is a traditional rite of passage for folks from wealthy backgrounds who are moving into the professions.” In other words, back to the Gilded Age. The young people who get that work experience will, of course, be more likely than those who don’t to move up the ladder. It’s a chicken-and-egg labor problem that, like unpaid internships, isn’t going away anytime soon.