On August 9, 2013, a hot, humid Friday, shortly after three in the afternoon, the laziest hour in the dreariest month for news in the nation’s capital, President Obama held a press conference in the East Room of the White House.

Two months earlier, Edward Snowden, a contractor with the National Security Agency, had leaked tens of thousands of highly classified documents, revealing that the NSA was intercepting phone calls and emails of millions of Americans, in apparent violation of the law—and tapping the phones of allied leaders abroad as well. Citizens were outraged, embassies were fuming, Silicon Valley executives were worried that they’d lose foreign customers who suspected their products had “back doors” that the NSA could enter. Something had to be done; the stench had to be contained, the trust restored. So President Obama announced that he was doing what many of his predecessors had done in the face of crisis—he was appointing a blue-ribbon commission.

Already, he and his advisers had chosen five candidates and asked the FBI to vet them for security clearances.

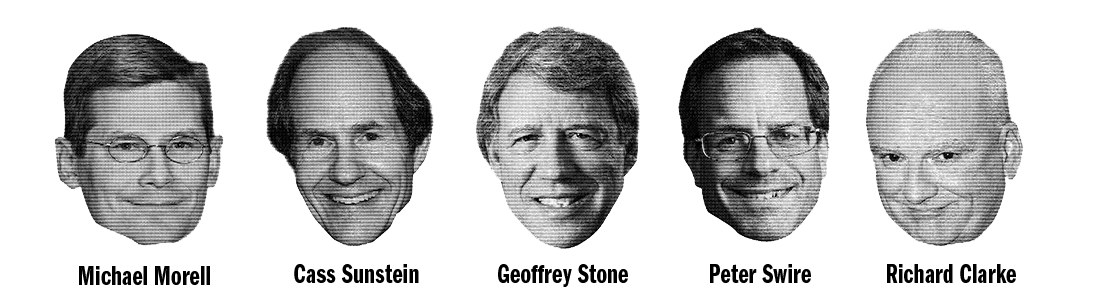

Michael Morell was the establishment pick among the five, a 33-year veteran of the CIA, who had just retired two months earlier as the agency’s deputy director and who’d been the point of contact between Langley and the White House during the secret raid on Osama bin Laden.

Cass Sunstein, a constitutional lawyer, had worked on Obama’s presidential campaign, served for three years as the head of his regulatory office, and was married to his United Nations ambassador, Samantha Power.

Geoffrey Stone, a law professor and member of the ACLU’s advisory council, had been dean of the University of Chicago’s Law School when Obama taught there in the 1990s.

Peter Swire, a law professor at the Georgia Institute of Technology and a White House aide to Bill Clinton, had written a landmark essay on surveillance law.

Finally, there was Richard Clarke, the White House chief of counterterrorism and cyber security policy under Clinton and (briefly) George W. Bush.

Clarke had resigned in protest over the 2003 Iraq invasion and, soon after, gained fame and notoriety during the 9/11 Commission’s hearings, testifying that Bush had ignored warnings of an impending attack by al-Qaeda.

On August 27, the five—christened as the President’s Review Group on Intelligence and Communications Technologies—met in the White House Situation Room with Obama and his top advisers. Obama gave the group a deadline of December 15 and assured them access to everything they needed. He made it clear that he didn’t want a legal analysis. Assume, he said, that we can do this sort of surveillance; your job is to tell me if we should be doing it as policy and, if not, to come up with something better.

Through the next four months, the group met at least two days a week, sometimes as many as four, often for twelve hours or longer, interviewing officials, attending briefings, examining documents, and discussing the implications.

On their first day of work, they were driven to NSA headquarters in Ft. Meade, Maryland. Clarke and Morell were the only ones who had been in the building before. Swire had dealt with some agency officials while working in the White House, considered them competent, but that was long ago. He was aware of court rulings that let the NSA invoke its foreign-intelligence authorities to monitor domestic phone calls, but Snowden’s documents, suggesting that it was using its powers as an excuse to collect all calls, startled him.

Stone, the one member who’d never had contacts with the intelligence world, expected to find an agency gone rogue. Stone was no admirer of Snowden: he valued certain whistleblowers, but Snowden’s wholesale pilfering of so many classified documents struck him as untenable. Maybe Snowden was right—he didn’t know—but he thought no national security apparatus could function if a junior employee decided which secrets to preserve and which to let fly. Still, the secrets Snowden revealed appalled him. Stone had written a prize-winning book about the US government’s tendency, throughout history, to overreach in the face of national security threats, and it looked like the reaction to 9/11 might be another case in point. He was already mulling ways to tighten the agency’s checks and balances.

Upon arrival at Ft. Meade, they were taken to a conference room and greeted by a half-dozen NSA officials, including the director, Gen. Keith Alexander, and his deputy, Chris Inglis. Alexander came and went throughout the day, leaving Inglis to run the meeting.

Inglis started with the most controversial program that Snowden had revealed: the bulk collection of telephone “metadata,” as authorized by Section 215 of the Patriot Act. As the news stories described it, this law allowed the NSA to monitor all phone calls inside the United States—not the conversations, but the phone numbers of those talking as well as the dates, times, and durations of the calls, which could reveal quite a lot of information on their own.

In fact, though, Inglis told the group, this was not how the program operated. Court rulings allowed the NSA to examine metadata only for purpose of finding associates of three specific foreign terrorist organizations, including al-Qaeda.

Clarke interrupted him. You’ve gone to the trouble of setting up this program, he said, and you’re looking for connections to just three organizations?

That’s all we have the authority to do, Inglis replied. Moreover, if the metadata revealed that an American had called a suspected terrorist’s number, just 22 people in the entire NSA—20 line personnel and two supervisors—could request and examine more data about the phone number. At least one supervisor had to approve the request. And the authority to search the suspect’s records would expire after six months.

The group then asked about the program’s results: How many times had the NSA queried the database, how many times were terrorist plots disrupted as a result?

One of the officials had the numbers at hand. For all of 2012, the NSA queried the database for 288 phone numbers. As a result, it passed on 12 tips to the FBI, which had the legal authority to investigate much more deeply. How many of those tips led to the halting of a plot? The answer was zero. None of the tips had led to anything.

Stone was floored. “Uh, hello?” he thought. “What are we doing here?” The much-vaunted metadata program seemed to be tightly controlled, did not track all phone calls in America, and hadn’t unearthed a single terrorist.

Clarke asked why the program still existed. Inglis replied that just because it hadn’t produced results so far didn’t mean it wouldn’t in the future. Besides, the metadata files existed; the phone companies routinely stored them as “business records”; why not use them as a potentially useful tool?

Inglis moved on to what he considered a far more damaging Snowden leak, the program known as PRISM, in which the NSA and FBI tapped into the central servers of nine leading U.S. Internet companies—Microsoft, Apple, Yahoo, Google, Facebook, AOL, Skype, YouTube, and Paltalk—extracting email, documents, photos, audio and video files, and connection logs. Gen. Alexander had released a statement, when the first stories broke about Snowden’s leaks, claiming that data gathered from PRISM had helped discover and disrupt 54 terrorist attacks, a claim that Inglis now repeated.

Did PRISM scoop up Americans’ email and cell phone calls along with targeted foreign communications, as the stories charged? Yes, the NSA officials said, but this was an unavoidable byproduct of the technology. Digital communications, they explained, travel in packets, which break up into pieces and flow along the most efficient paths before reassembling at their destination. Because most of global bandwidth was concentrated in the United States, pieces of almost every email and cell phone conversation in the world flowed, at some point, through a line of American-based fiber optics. If a terrorist in Pakistan was talking with an arms supplier in Sudan, there was no need to place a listening post in hostile territory. Instead, pick up the strand that came through fiber-optics cable inside U.S. territory and hop on.

In the age of landlines and microwave transmissions, if a terrorist in Pakistan called a terrorist in Yemen, the NSA could intercept their conversation without restraint; now, though, if the same two people, in the same overseas locations, were talking on a cell phone, and if NSA analysts wanted to latch on to a packet containing a piece of that conversation while it flowed inside the United States, they would have to get a warrant from the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court. It made no sense.

That’s what led to the Protect America Act of 2007 and to the FISA Amended Act of 2008, especially Section 702, which allowed the government to conduct electronic surveillance inside the United States—“with the assistance of a communications service provider,” in the words of that law—as long as the people communicating were “reasonably believed” to be outside the United States.

Read: FISA Amendments Act of 2008, Section 702

The nine Internet companies, which were named in the news stories, had either complied with NSA requests to tap into their servers or been ordered by the FISA Court to let the NSA in. Either way, the companies had long known what was going on.

The commissioners asked the obvious question: what did “reasonably believed” mean? How did the NSA make this assessment?

The briefers went through a list of “selectors”—key-word searches and other signposts—that indicated possible “foreignness.” As more selectors were checked off, the likelihood increased. The intercept could legally begin, once there was a 52% chance that both parties to the call or the email were foreign.

Some on the committee winced. This seemed an iffy calculation and, in any case, 52% was a low bar. The briefers conceded the point. Therefore, they went on, if it turned out, once the intercept began, that the parties were inside the United States, the operation had to be shut down at once and all its data destroyed.

They also noted that the NSA couldn’t go hunting for just anything. The law required that, each year, the NSA director and the U.S. Attorney General had to certify the categories of intelligence targets that PRISM could intercept. Then, every 15 days after the start of a new intercept, a special Justice Department panel reviewed the operation, ensuring it conformed to that list. Finally, every six months, the Attorney General reviewed all the start-ups and submitted them to the congressional intelligence committees.

There was, however, a problem. The data packets swooped up by the NSA were often intermingled with packets carrying communications by Americans. What happened to all of those pieces? How did the agency ensure that some analyst didn’t read those emails or listen to those conversations?

President Obama had recently declassified a ruling by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, excoriating the NSA for having treated these emails improperly and ordering that PRISM be shut down until the NSA devised a remedy. The briefers acknowledged this, outlined the changes they’d made to the program’s architecture, and produced a recent ruling by the same judge, pronouncing himself satisfied that the problem was solved.

All the briefers’ claims would have to be verified, but all in all, the group’s first day of work was productive. The NSA officials had answered every question seemingly with candor and even an interest in discussing the issues. They’d rarely discussed these matters with outsiders—until then, no outsider had been cleared to discuss them—and they seemed to relish the chance. Stone was particularly impressed. Most of the checks and balances that Stone had thought about proposing, it turned out, were already in place.

Over the next few weeks, as the commissioners and their staff reviewed stacks of highly classified NSA documents, they concluded that most of that briefing was accurate: the PRISM intercepts did play a role in halting 53 terrorist plots (not 54, as claimed, but close enough)—and the metadata analysis had no effect whatever. Still, the commissioners were split on what to do about metadata: Clarke, Stone, and Swire wanted to recommend killing the program; Morell and Sunstein bought the argument that, even if metadata hadn’t stopped any plots so far, it might in the future.

Then, during one of the subsequent meetings at Ft. Meade, Gen. Alexander told the group that he could live with an arrangement where the telecom companies held on to the metadata, with the NSA able to gain access to specified files through a court order. It might take a little longer to obtain the data this way, but not by much—a few hours maybe. Alexander also revealed that the NSA once had an Internet metadata program, but it proved very expensive and yielded no results, so, in 2011, he terminated it.

This settled the debate. If Alexander had no problems with storing the metadata outside Ft. Meade, the commissioners wouldn’t either.

The brief dispute over metadata had sparked one of the few fits of rancor among the members. Given their disparate backgrounds and politics, they’d expected to be at each other’s throats. From early on, though, the atmosphere was harmonious.

The camaraderie took hold on their second day of work, when the five went to FBI headquarters, at the J. Edgar Hoover Building, in downtown Washington. The group’s staff had requested detailed briefings on the bureau’s relationship with the NSA and on its own version of metadata-collection, known as National Security Letters, which allowed access to American phone records and other transactions deemed “relevant” to investigations into terrorism or clandestine intelligence activities. Unlike the NSA’s metadata program, the FBI’s had no restrictions at all: the letters required no court order; any field officer could issue them, with the director’s approval; and recipients of a letter were prohibited from ever revealing they’d received one. (Until a 2006 revision, they couldn’t even inform their lawyers.) Not merely the potential, but actual instances, of abuse seemed likely.

When the five arrived at the bureau’s headquarters, they were met not by the director or his deputy but by the third-ranking official, who took leave after escorting them to a conference room, where 20 FBI officials sat around a table prepared to drone through canned presentations describing their jobs, one by one, for the hour that the group had been allotted.

Ten minutes into the dog-and-pony show, Clarke asked about the briefings they’d requested. One of the officials sidestepped his question. The canned briefings resumed, but after a few more minutes, Clarke stood up and said, “This is bullshit. We’re out of here.” He walked out of the room; the other four sheepishly followed, while the FBI officials sat in shock. At first, Clarke’s colleagues were a bit mortified too. They’d heard about his arrogance and his power-play antics and wondered if this was going to be standard procedure.

But by the next day, it was clear that Clarke had known what he was doing. Word quickly spread about “the bullshit briefing,” and from that point on, no federal agency dared greet the group with condescending show and tell. Only a few agencies proved very useful, but they all at least tried to be substantive, and even the FBI called back for a second chance.

Clarke’s act emboldened his colleagues to press more firmly for answers to their questions. They derived an esprit de corps from being the first group of outsiders to ask these questions on behalf of the president. As the air lightened from cordial to jolly, they started calling themselves “the five guys,” after the name of a local hamburger joint, and referring to the big book they’d soon be writing as “The Five Guys Report.”

They divvied up the writing chores, each drafting a section or two and inserting ideas on how to fix the problems they’d diagnosed. It added up to a 303-page report with 46 recommendations for reform. They voted by secret ballot on each proposal and discovered, to their surprise, that they agreed unanimously on all 46.

One of their key recommendations—the one that garnered the most attention and controversy—was to remove the metadata files from Ft. Meade and store them with the private telecom companies, allowing NSA access only through a specific court order.

Also, lest anyone interpret the report as an apologia for Snowden (whose name appeared nowhere in the text), ten of the 46 recommendations dealt with ways to tighten the security of classified information inside intelligence agencies, including procedures to prevent computer system administrators—which had been Snowden’s job at the NSA facility in Oahu, Hawaii—from gaining access to documents unrelated to their work.

On December 13, two days before deadline, the Review Group members turned in their report. To their minds, they fulfilled their main task—as their report put it, “to promote public trust, while also allowing the intelligence community to do what must be done to respond to genuine threats”—but also exceeded that mandate, outlining truly substantive reforms to the surveillance system.

Their language was forthright in ways bound to irritate all sides of the debate, which had only intensified in the six months since the Snowden affair. “Although recent disclosures and commentary have created the impression, in some quarters, that NSA surveillance is indiscriminate and pervasive across the globe,” the report stated, “that is not the case.” However, it went on, the group found “serious and persistent instances of noncompliance” in the NSA’s “implementation of its authorities,” which, “even if unintentional,” raised “serious concerns” about its “capacity to manage” its powers “in an effective, lawful manner.”

To put it another way, while the group found “no evidence of illegality or other abuse of authority for the purpose of targeting domestic political activities,” there was always present “the lurking danger of abuse.” In a passage that might have come straight out of Stone’s book, the report stated, “We cannot discount the risk, in light of the lessons of our own history, that at some point in the future, high-level government officials will decide that the massive database of extraordinarily sensitive private information is there for the plucking.”

On January 17, 2014, in a speech at the Justice Department, Obama announced a set of new policies prompted by the report. He adopted some of their suggestions, rejected others. But the biggest news was that he endorsed the removal of metadata files from Ft. Meade.

The endorsement seemed doomed, though, because changes in metadata collection would have to be approved by Congress, and it seemed unlikely that this Republican Congress would schedule a vote; its leaders had no desire to change intelligence operations. But they found themselves forced into a vote. Congress had passed the Patriot Act, days after the 9/11 attacks, in great haste. Few even had time to read the bill before voting on it, so key Democrats insisted that a sunset clause, an expiration date, be written into certain sections of the law—including Section 215, which allowed the NSA to store metadata—so that Congress could extend the provisions, or let them lapse, at a calmer time.

In 2011, when the provisions were last set to expire, Congress voted to extend them until June 2015. In the interim four years, three things happened. First came Snowden’s disclosures. Second, the Five Guys Report concluded that metadata hadn’t nabbed a single terrorist. Third, on May 7, just weeks before the next expiration date, the U.S. 2nd Court of Appeals ruled that Section 215 of the Patriot Act did not in fact authorize anything as broad as the NSA’s bulk metadata collection program. The judges in fact called the program illegal, though they stopped short of deeming it unconstitutional and noted that Congress had the right to authorize the program explicitly.

So the matter was left in the hands of Congress, and Congress had to act. Owing to the sunset clause, if it didn’t vote at all, the metadata program would die on its own. At the same, there weren’t enough votes to keep the program alive in its current form. So, in a bill called the USA Freedom Act, Congress voted to adopt the reform suggested by the Five Guys—and endorsed by Obama. (Ironically, Republican opponents complained that the bill “eviscerated” the NSA’s intelligence capabilities, not knowing that its core idea had come from the NSA director.)

This measure wouldn’t change much about the long reach of the NSA or its foreign counterparts. For all the political storms it stirred, bulk collection of metadata comprised a tiny portion of the agency’s activities. But the reforms would block a tempting path to potential abuse, and they added an extra layer of control over the agency’s power—and its technologies’ inclination—to intrude into the everyday lives of Americans.

On March 31, two and a half months after Obama’s speech at the Justice Department, Stone delivered a speech at Ft. Meade. The NSA staff had asked him to recount his work on the Review Group and to reflect on its lessons.

Stone started off by noting that, as a civil libertarian, he’d approached the NSA with skepticism, but was quickly impressed by its “high degree of integrity” and “deep commitment to the rule of law.” The agency made mistakes, but they were just that—mistakes, not intentional acts of illegality. It wasn’t a rogue agency; it was doing what its political masters wanted and what the courts allowed, and, while reforms were necessary, its activities were generally lawful.

But his speech then took a sharp turn. “To be clear,” he emphasized, “I am not saying that citizens should trust the NSA.” The agency needed to be held up to “constant and rigorous review.” It work was “important to the safety of the nation,” but, by nature, it posed “grave dangers” to democratic values.

“I found, to my surprise, that the NSA deserves the respect and appreciation of the American people,” he summed up, “but it should never, ever be trusted.”

Fred Kaplan is a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and the author of Dark Territory.

This is excerpted from Dark Territory: The Secret History of Cyber War, by Fred Kaplan. © Fred Kaplan