or the first time in her life, Yazmin Ali is afraid to leave her house. Unlike most neighbors in her family’s cookie-cutter subdivision outside Fredericksburg, VA—where homes have Christmas wreathes on the front doors and cars have American flag vanity plates—she’s Muslim, and she wears a hijab.

or the first time in her life, Yazmin Ali is afraid to leave her house. Unlike most neighbors in her family’s cookie-cutter subdivision outside Fredericksburg, VA—where homes have Christmas wreathes on the front doors and cars have American flag vanity plates—she’s Muslim, and she wears a hijab.

It doesn’t matter that Ali, 34, was born and raised in Florida, that her mother is an evangelical Christian Cuban-American, that she a masters degree from Auburn, or that she only learned Arabic through a State Department scholarship in Jordan—when it was raining at her kids’ bus stop recently and she offered to let other parents shelter in her car while they wait, she says, they said no.

Dirty looks are nothing new—she’s been tripped before at the mall—but events in the last month have taken a sobering turn. Four days after the ISIS attacks in Paris, her mosque, the Islamic Center of Fredericksburg, held a long-planned meeting to share plans for its new building with the community. A protestor started shouting, “Every Muslim is a terrorist!” Soon after, ICF hosted a coat drive for Syrian refugees with a neighboring church, and a man with a confederate flag showed up with a sign, “No refugees in VA.” After the San Bernardino shooting, Ali started disguising her hijab under a winter hat and scarf. “I had a really long, good cry,” she says. “Because I have kids, I’m fearful of something happening to me.”

Ali is now organizing a self-defense class for fellow Muslim women, and she’s pushing her mosque to display the American and Virginia flag. She still plans to take Christmas cookies to her neighbors. And she is choosing to keep her hijab on. “To take it off almost means I’ve allowed hate to permeate and penetrate my identity,” she says. “As much as it would make my life easier, I can’t.”

hese are difficult times for American Muslims, as anecdotal reports suggest terror fears are sparking a backlash. Trends are worrying. According to one tally, there were 38 U.S. anti-Islamic attacks in since the Paris terrorism. The trend was also bad last year, with the FBI reporting hate crimes decreased for all categories of victims except Muslims. The last month was especially troubling. Vandals tore up pages of the Quran and left it covered with feces at a mosque in Pflugerville, Texas. An Indiana University student allegedly attacked a Muslim woman at a café, choking her and removing her scarf. In Grand Forks, N.D., a Somali business was firebombed after it was defaced with Nazi-like symbols. A severed pigs’ head was tossed at a Philadelphia mosque from a passing pickup truck.

hese are difficult times for American Muslims, as anecdotal reports suggest terror fears are sparking a backlash. Trends are worrying. According to one tally, there were 38 U.S. anti-Islamic attacks in since the Paris terrorism. The trend was also bad last year, with the FBI reporting hate crimes decreased for all categories of victims except Muslims. The last month was especially troubling. Vandals tore up pages of the Quran and left it covered with feces at a mosque in Pflugerville, Texas. An Indiana University student allegedly attacked a Muslim woman at a café, choking her and removing her scarf. In Grand Forks, N.D., a Somali business was firebombed after it was defaced with Nazi-like symbols. A severed pigs’ head was tossed at a Philadelphia mosque from a passing pickup truck.

The Islamic Center of Fredericksburg, 65 miles south of Washington, D.C., is not exempt. When the protestor shouted, “Every Muslim is a terrorist!” at the community meeting in late November, other attendees cheered. Soon after, flyers appeared at the local mall, rallying people to fight the mosque’s building project. “No Jihad in Fredericksburg!!” the signs read. “Do we want their Jihad and bloodshed in our streets? NO! … There is no way of knowing how many ISIS agents will be hiding among them!”

The ICF community is not used to the spotlight. It has been in the area for 27 years, and its current mosque is a small building with fewer than 50 parking spots, next to the Fire Department office and across from a Goodwill store. But its community is vibrant. On Friday nights, more than 300 families regularly come to pray, cars spilling beyond the property. Parking is need enough to build a new center—high holidays like Eid can bring in 1200 people. Most are Americans, and their family histories are diverse across the globe: Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, Sudan, Somalia, Malaysia, Kenya, the Gulf countries. And in Spotsylvania county—where a highway sign wishes Jesus a Happy Birthday, a Baptist church sign reads “It is better to be Biblically correct than politically,” and four out of five people are white—they stand out.

TIME interviewed more than a dozen members of the Islamic Center of Fredericksburg in mid-December. All were American citizens. They share fear for their physical safety, fear for their children’s future, and deep concern about the future of America’s political leadership. Nearly half were planning to vote Republican until Donald Trump promoted an anti-Muslim platform. And yet, in the midst of the growing hate, many in their community have also shown them overwhelming support. It is a reminder that their country has a choice to make. And they hope a narrative of unity will win.

ours after the man interrupted their building meeting, Ahmad Imran, a doctor at Mary Washington Hospital, and his wife Marriam decided to pull their two children out of the mosque’s Sunday school program. The violent outburst suggested too much of a future risk for their safety, they explain. “I always believed America was the greatest country in the world,” Ahmad, a U.S. citizen born in Lahore, Pakistan, says. “It was an eye-opener for us—at that moment I didn’t see a difference between America and a third world country.”

ours after the man interrupted their building meeting, Ahmad Imran, a doctor at Mary Washington Hospital, and his wife Marriam decided to pull their two children out of the mosque’s Sunday school program. The violent outburst suggested too much of a future risk for their safety, they explain. “I always believed America was the greatest country in the world,” Ahmad, a U.S. citizen born in Lahore, Pakistan, says. “It was an eye-opener for us—at that moment I didn’t see a difference between America and a third world country.”

Once the mosque hired a private security firm, the Imrans began to relax, but only slightly. The incident shook them to the core. “All night we were awake thinking, what will we do?” Marriam says. “How will we raise our kids with so much hate?”

“I am afraid that one day living in their country of love and of birth, they will be subjected to hateful comments and taunts just because of their name and faith,” Ahmad says. “Nobody will find out that they love and practice kindness, and they try to help their fellow human beings.”

Sara Shanab, 19, and her brother Mohamed, 18, both have gotten the bad looks in public—she works at a bank, he at Panera Bread. But at the community college where they both study, they explain, younger people are more open-minded. When his dad told him not to wear a cap with Arabic on it out of the house, Mohamed was more amused than afraid. When a protestor showed up at their mosque recently, Sara offered him pizza. “He thinks he is tearing us apart,” she says. “It just shows how misinformed he is.”

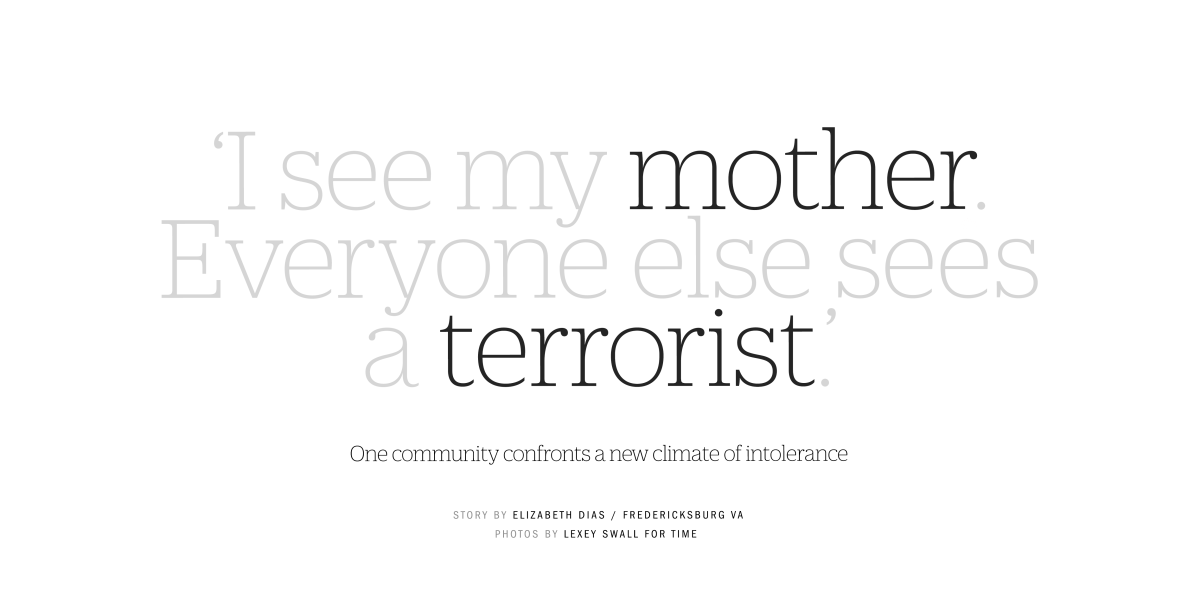

But they are afraid for their mother, who wears a hijab and is a substitute teacher at a public school. She had told them about the “hijab challenge” where people try to pull off as many scarves as they can off of Muslim women. Sara bought her mother pepper spray. “I see my mother. Everyone else sees a terrorist,” Mohamed says.

Recently the siblings decided to start a Muslim student group on their campus. They go on hiking trips, feed the homeless, and plan to attend an interfaith rally in Washington, D.C. this month. “You can’t tell me I am less American just because I believe in a different religion,” Sara says. “The Pledge of Allegiance says ‘justice for all.’” Mohamed adds, “I feel like it’s going to get better.” But Sara clarifies: “It depends on who gets elected.”

The upcoming presidential election is a live question for everyone interviewed at ICF—everyone interviewed plans to vote. Muhammad Asif, a doctor at Mary Washington Hospital, and his wife Saima Rana are concerned that political leaders are driving fear for their own gain. After Republican frontrunner Donald Trump announced that he would ban all Muslims from entering the U.S., their youngest, a first-grader, came home from school and announced, “Donald Trump doesn’t like us—we should go to Canada.” They were shocked. “My son was asking, What is sharia law? I was like, I don’t know,” Rana said, explaining that she had to look it up online. “Why should I teach [my children] hatred, why not something good?”

The couple had been planning to vote Republican because of tax policy, but now, given the anti-Muslim proposals they are hearing from Trump and the lack of support they are receiving from other candidates like Sen. Ted Cruz, they have changed their minds and will vote Democrat. “I will vote for a person who will protect my liberty and freedom,” Asif, who is on the mosque’s board, says. “This may go on for one, two, ten years, but in 50 years, people will say, these are the people who damaged the country.”

Nancy Qualls-Shehata, 48, dismisses Trump outright as unelectable, and is a Bernie Sanders fan. She converted to Islam 23 years ago in Kansas City, Mo. Now she and her husband, an imam, own their own small business, selling products online, and have been raising their five children in Fredericksburg for nearly 12 years. But unlike others, she doesn’t feel as though she has been targeted. Fredericksburg is a military town, she explains—the Dahlgren Naval Facility and the Quantico Marine Corps Base are close by—and if it hadn’t been for the “Every Muslim is a terrorist” incident at the planning meeting, she’d not have noticed a difference in her community, she says. Recently she was purchasing new items at a military store for her teenage son, the first Muslim in his civil air patrol squadron. The reception at the store, typically “a redneck place,” as she put it, was totally normal, non-threatening, no weird looks. “Fredericksburg has more good than negative,” she says. “Maybe it’s because I’m white.”

But even Qualls-Shehata is being cautious. Last weekend, she picked up passport applications for her whole family, so they can leave the country if things get bad. “It’s called prudence,” she says. “Everything is in the hands of Allah. I am aware. I am not worried.”

hen the San Bernardino shooting happened just days before ICF was scheduled to host a second public building project meeting, Samer Shalaby—the target of the “Every Muslim is a terrorist” outburst a few weeks prior—and other mosque leaders decided to cancel the meeting. They replaced it with a community open house to welcome neighbors to their space. “As awful as that [first] experience was, and make no mistake, I’ve never seen Samer so shaken in our 28 years of marriage—so much good has come from it,” Cathy, Samer’s wife, tells TIME in an email.

hen the San Bernardino shooting happened just days before ICF was scheduled to host a second public building project meeting, Samer Shalaby—the target of the “Every Muslim is a terrorist” outburst a few weeks prior—and other mosque leaders decided to cancel the meeting. They replaced it with a community open house to welcome neighbors to their space. “As awful as that [first] experience was, and make no mistake, I’ve never seen Samer so shaken in our 28 years of marriage—so much good has come from it,” Cathy, Samer’s wife, tells TIME in an email.

Support poured in via phone calls, emails, and even some donations for their new mosque. Encouragement—from neighbors, business associates in Spotsylvania County, the American Muslim community, every denomination of Christians, Jews and atheists, all over the U.S. and even from Europe—has been overwhelming, Cathy says. “Since the lead offender at the meeting identified himself as a veteran, it has been especially touching to receive support from so many veterans of Middle East deployments,” she writes. “They specifically and repeatedly express that the Constitution protects ALL Americans, and they confirm that MOST of the Muslims they saw were average people who practice their faith and want nothing to do with the extremists. Here’s an example from one vet: ‘I would gladly help protect your mosque from intolerant people who confuse the actions of a few with the faith of many.’”

Two strangers approached the Samers’ daughter-in-law in Fredericksburg. One older lady gave her a hug “because she probably needs it right now,” Cathy shares, and a man fumbled with his cell phone and read “Assalam alaykum” (peace be to you). He explained that he had practiced it “so that if he saw a Muslim lady, he could greet her peacefully and respectfully.”

Grace Church of Fredericksburg, an evangelical charismatic congregation, invited ICF to co-host a coat drive for Syrian refugees, and leaders attended an open house at ICF last week. When protestors calling themselves “Christian patriots” showed up at both events, Cathy says, “our Christian guests asked us to stay back while they confronted the protesters and chided them for being un-Christian.”

Even while TIME was interviewing Ahmad and Mariam Imran, a senior citizen wearing a UVA belt walked up from the parking lot. At first he stood awkwardly, appearing to not know what to say. Then he identified himself as a resident of the Celebrate Retirement community a few miles north. “I just came by to express my support,” the man, Paul Bonner, said.

Now more than ever it is difficult to know what direction the country will choose, Marriam says. She knows it could get worse. But she and her husband are trusting the prejudice will pass. “There is an overwhelming majority of people in America who love and respect other people, regardless of their ethnic and religious backgrounds,” Ahmad says. “These good-hearted people will take this great country forward.”