Warning: This story contains spoilers for Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story by Martin Scorsese.

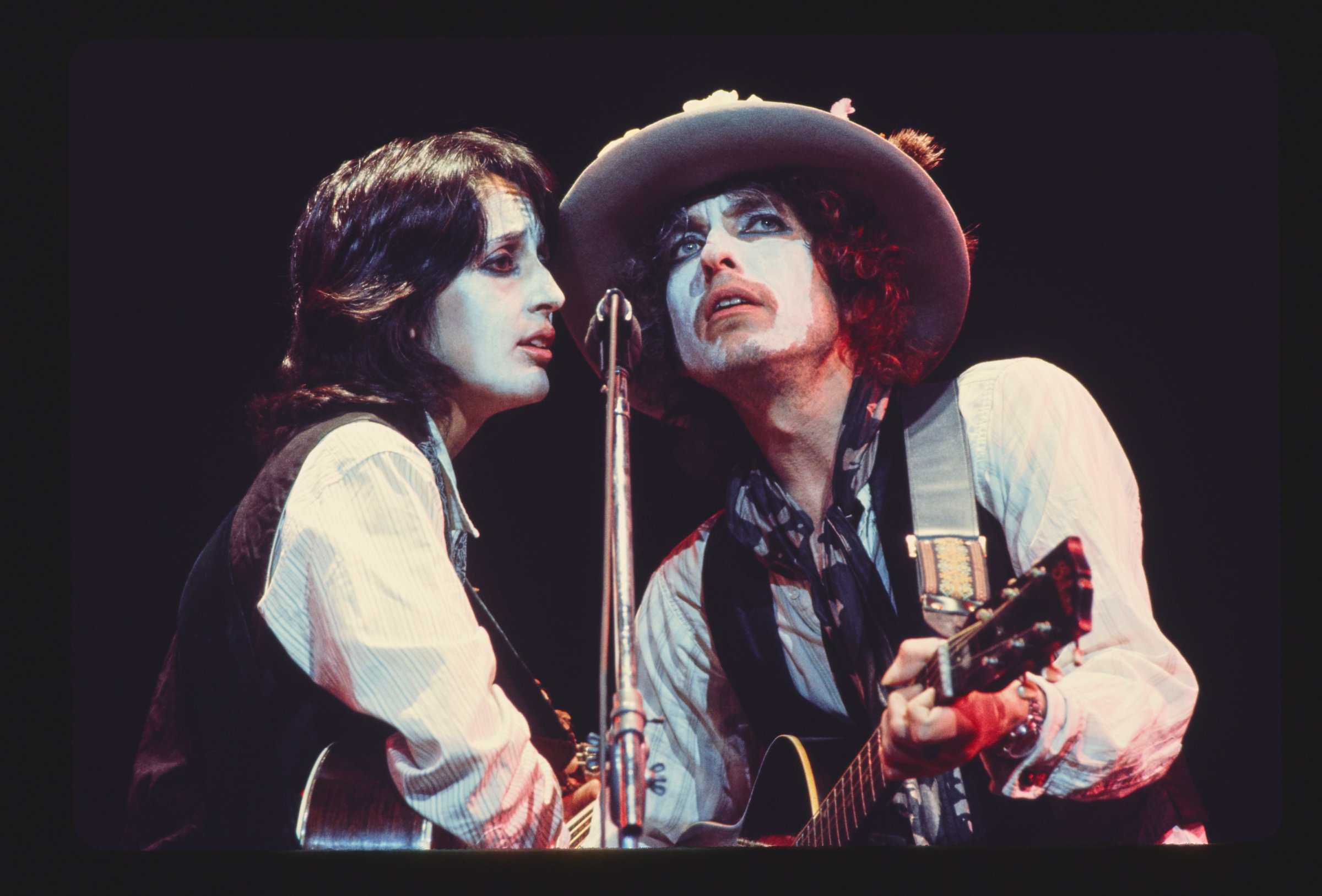

Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story by Martin Scorsese looks a lot like a documentary. The film is ostensibly a 1975 tour diary, with grainy footage showing Dylan and his merry band of compatriots—which includes Joan Baez, Joni Mitchell and Allen Ginsberg—performing at concerts, flirting backstage, eating at greasy-spoon joints and sniping at each other. There are solemn talking-head interviews, archival photographs and crackling voiceovers—all the trappings of nonfiction filmmaking.

But appearances can be deceiving, especially when it comes to Bob Dylan. In 1961, a 19-year-old named Bobby Zimmerman showed up in New York, gave himself a new name and told people he was a former teen vagabond who had joined the circus—excising his actual upbringing in a middle-class Jewish family in Minnesota.

Dylan has twisted fact and fiction around each other ever since, employing feints and double feints to obscure mundane truths in service of larger ones. And Rolling Thunder Revue is no exception. The Netflix film—which arrives June 12 alongside a 14-CD box set release of live recordings—is described on that website as an “alchemic mix of fact and fantasy”: It contains both spellbinding concert footage from the tour as well as false characters, made-up vignettes and hyperbolic intrigue.

“This is a very unfactual thing—and totally in keeping with Dylan’s oeuvre,” Rob Stoner, who was the tour’s music director, told TIME about the new film. “It’s full of metaphors and questions and leaves you wanting more.”

TIME talked to several people who were on the Rolling Thunder tour—two musicians, a manager and a journalist—to sort out the truths and myths in Scorsese’s film.

What was the Rolling Thunder Revue?

The Rolling Thunder Revue was a tour that Bob Dylan conceptualized as an alternative to the regimented big-budget tours that pervaded ’70s rock-star culture. More than a decade into his career, Dylan himself was a massive rock star at that point and had gone on such a tour the year before, flying on private jets and playing to large arenas. He told his longtime friend Louie Kemp that he wanted to model his new tour after the traveling carnivals they would see in their hometown of Duluth, Minnesota.

“They’d be in town for a few days and then they’re gone,” Kemp recalls. “They had their own mystique and excitement.” Dylan has also said that he was inspired by Italian commedia dell’arte troupes from centuries ago, in which a colorful cast would put on improvised shows while wearing masks and lavish costumes.

Dylan asked Kemp, who was the president of a fish company, to manage the sprawling tour. They would play at small venues in small towns and wait until the last minute to tell even the performers where they were headed; they would forgo large-scale promotion in favor of paper handbills passed out the week before.

“‘I want to do this one for people who wouldn’t ordinarily get a chance to have a good seat at my shows,’” Kemp paraphrases how he recalls Dylan explaining his rationale. “‘I want the people on the tour to have fun also: This should be a fun trip for everybody involved.’”

What was the tour like for those on it?

Dylan decided that the core of his touring band would be the same as the one on his Desire album, which he had recorded a few months prior: the bassist Rob Stoner, the drummer Howie Wyeth and the violinist Scarlet Rivera. But the group quickly ballooned as he held open rehearsals and jam sessions in New York City’s Greenwich Village, inviting guests and carousing until the early hours of the morning. Before long, the cast included rock stars (Roger McGuinn of the Byrds and Mick Ronson, who played with David Bowie among others), poets (Allen Ginsberg and Peter Orlovsky), folkies (Ramblin’ Jack Elliott and Joan Baez) and many more.

McGuinn was planning his own tour but postponed it once Dylan asked him aboard. He did not regret his decision: ”It was the best party I’d been to,” he told TIME. He recalled jamming with Dylan and Joni Mitchell at a party at the home of singer-songwriter Gordon Lightfoot—”Allegedly somebody threw a leather jacket into the fireplace,” he recalled—and sitting on the bus next to Mitchell, who joined the tour midway through, while she wrote songs that would end up on her forthcoming album, Hejira. “She had this little composition book, the speckled black-and-white thing like kids have in school,” he said. “It was all full of new songs. She’d be writing things she saw, like the white lines on the highway.”

Were there ego issues on the tour?

Rolling Thunder Revue amplifies the backstage drama of the tour, depicting squabbles between bandmates, journalists, promoters and even the camera crew. The guitarist Stephen Soles says in a talking-head interview that the atmosphere was “like the court of Henry VIII.”

But Stoner said the atmosphere was much different than portrayed. “That’s a bunch of sensationalist crap that they tried to edit in there,” he said. “It was all very mellow.”

McGuinn agreed: “I think we all knew we had to check our egos at the door,” he said. “It was very friendly.” He said that the energy of the tour was lifted by the presence of Ginsberg, who would lead dance sessions and write poems as part of a newsletter slipped under the hotel room doors of those on tour. “Ginsberg was like a big teddy bear,” he said. “A really friendly, loving guy—he was a lot of fun to be around.”

Was Allen Ginsberg actually forced to do luggage duty?

While Kemp told TIME that Ginsberg was the “moral compass” of the tour, Jim Gianopulos—who says he served as a promoter on the tour (more on that below)—revealed in an onscreen interview that Ginsberg’s role was diminished as the tour went on. Gianopulos says that Ginsberg and fellow poet Peter Orlovsky became baggage handlers after their poetry sets were cut for time. The notion that one of the most revered American poets would be reduced to a roadie seems absurd, and is unlikely to be true. “I never saw Allen schlepping around cases,” Larry “Ratso” Sloman, a journalist who covered the tour for Rolling Stone, told TIME. Sloman said that Rolling Thunder Revue footage in which Orlovsky commiserates with Sloman about his new luggage duties was “tongue in cheek.”

So why did Jim Gianopulos say that?

Gianopulos, the current CEO of Paramount Pictures, appears in interviews throughout the film as a pompous suit whose sole aim is to make money. He badmouths Louie Kemp and decries the tour as a “disaster, a catastrophe.”

But Gianopulos wasn’t actually there, according to Kemp. “It’s a character they drew in,” he said.

Wait—who else is in the movie who wasn’t actually on the tour?

A Michigan representative called Jack Tanner is interviewed in the film, claiming that Jimmy Carter hooked him up with tickets to the concert in Niagara Falls. But there was no such senator at the time. The character is played by the actor Michael Murphy. (Jack Tanner was a fictional character in the 1988 Robert Altman/Garry Trudeau mockumentary Tanner ’88.)

Sharon Stone also shows up in interviews, saying that she joined the tour as as a 19-year-old—and that her KISS shirt inspired Dylan’s onstage face paint. But Stone was actually 17 at the time—and neither McGuinn nor Kemp remember her on the tour. When asked about the KISS connection to Dylan’s face paint, McGuinn said, “I don’t think it had anything to do with KISS. I can’t imagine that. I think he was more going for a mime look than KISS.”

Another one of the central characters is the filmmaker Stefan Van Dorp, who says in the film that he was brought on to record concert footage and B-roll. He tussles with Sloman, demands credit for his work on the film, and scoffs at the idea that Bob Dylan is a genius. At the Rolling Thunder Revue premiere in New York City in June, Van Dorp even appeared onstage to help introduce Martin Scorsese.

But Van Dorp, like Tanner, is a fictional creation, played by the actor Martin von Haselberg. His reedy voice was inserted into many scenes, and at one point a doctored photo of him appears, with Sloman lurking in the back of the frame.

When Sloman watched the film in an advance screening several weeks ago, he was at first bewildered by the outsize presence of a man he had no recollection of. “It took me about three segments of going, ‘Who the hell is this guy?’ before I realized what they were doing,” he said.

So if Van Dorp didn’t exist, who shot all of the footage?

At long last, we get to the crux of the creation of the Rolling Thunder Revue. In 1975, at the beginning of the tour, Dylan told Kemp that he wanted to shoot a film on the road. He hired the playwright Sam Shepard to write the script and come along for the ride. (His relationship with Joni Mitchell would form the basis for her song “Coyote,” which the film shows her playing alongside Dylan and McGuinn.)

In Rolling Thunder Revue, Van Dorp says he and Shepard were working together. But in reality, Shepard was writing the bones of what would become Renaldo and Clara, a part-documentary, part-narrative film released in 1978.

Renaldo and Clara was directed by Dylan and shot by Howard Alk, David Meyers and Paul Goldsmith—and like Rolling Thunder Revue, it consists of concert footage, documentary interviews and fictional vignettes. Some vignettes were scripted by Shepard—but given that his actors were musicians, most scenes devolved into improvisations by Dylan, his wife Sara, Joan Baez, Jack Elliott, and many others on the tour, who played amorphous and ill-defined characters.

“It was a Sisyphean task, because none of these musicians were going to memorize this sh-t,” Stoner said.

Renaldo and Clara ran for four hours and was met with widespread ridicule upon release for its bloat and lack of coherence. And while the film is never mentioned in Scorsese’s Rolling Thunder Revue, much of the new film’s footage is pulled directly from the old one, as well as from its outtakes, shot by Alk and his team. One new scene, for example, shows Bob Dylan and Joan Baez flirting and rehashing their old relationship, and is presented as documentary footage. But an extremely similar scene also occurs in Renaldo and Clara, in which Dylan and Baez’s characters (Renaldo and the Woman in White, respectively) discuss marriage—with the same camera angle, costumes and demeanors.

Why did Scorsese and Dylan make a film like this?

Netflix did not make Scorsese, Dylan or the film’s producers available for this article. “Bob has been known to play and to create a whole mythology around him,” Sloman said. Perhaps Scorsese wanted to pay homage to the fluid and fable-filled format of Renaldo and Clara; perhaps Dylan—who gives talking-head interviews full of falsehoods throughout the film—saw the film as an opportunity to extend his trickster impulses and his constant desire for reinvention.

Stoner has another theory, based on the fact that Renaldo and Clara was a commercial and critical failure. “Maybe that’s one of the reasons he and Scorsese have conspired to recycle some of it in this current project: as a vindication,” he said. “To say: ‘See, Renaldo and Clara wasn’t all terrible!’”

If the film spends so much time on fictional characters, which real figures does it leave out?

Stoner’s central complaint with the film is that it makes only one mention of Jacques Levy, the theater director who was tasked with crafting each performance. “Leaving out Jacques Levy is ridiculous. He’s the guy who staged the thing, put it together, blocked all the acts,” Stoner says. “Also, his experience as a clinical psychologist was invaluable in being a go-between for a lot of people on the tour.”

So what was Bob Dylan really like on the Rolling Thunder Revue of 1975?

In Scorsese’s film, Dylan appears in several mystifying iterations. In the footage from 1975, he appears both as Bob Dylan and Renaldo, coming off as an aloof leading man who repeatedly refuses interviews to the cameraman (the fictional Van Dorp’s pleas behind the camera are edited in). In more recent talking-head interviews for Rolling Thunder Revue, he snipes at his old bandmates and repeatedly deflects, obfuscates and lies. When asked what the tour was about, he says, “It’s about nothing. It’s just something that happened 40 years ago.”

But those on the tour say that Dylan’s film persona couldn’t be more different from his actual demeanor on the tour. “He never felt or acted like he was the star of the show,” Kemp said. “He was just one of the gang.”

Sloman agreed: “It was the loosest I’ve ever seen him,” he said. “I felt that the burden of stardom had been lifted from him—he didn’t really have a need for that Dylan persona.”

Dylan was also reaching a musical peak at the time. His voice gained a heft and had lost its youthful quaver, and his stamina onstage was unrelenting. And while many aspects of Rolling Thunder Revue should not be looked to for veracity, the performances themselves are ironclad: It’s remarkable to watch Dylan rip through songs like “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall,” “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door” and “Hurricane” with a newfound focus and ferocity.

“His memory was incredible: He could do these 10- to 15-verse songs and remember every word and spit them out like a machine gun,” McGuinn recalled. “I thought he was on top of his game.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com