Every two years, the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City presents a survey of contemporary work aiming to represent the current state of art-making in the U.S. Throughout its nearly century-long history, the Whitney Biennial has been a showcase for significant American artists on the rise. It has also remained a flashpoint for public protest and a stage for larger cultural tensions bubbling beyond the gallery walls.

This history is exemplified by a controversy surrounding a painting of the mutilated body of Emmett Till by Dana Schutz, a white artist, at the 2017 Biennial. Many saw the painting as a tone-deaf exploitation of black suffering, and it sparked demonstrations in the gallery, online discourse about institutional racism and even demands for the painting’s destruction. This year has seen protest, even before the Biennial’s May 17 opening, over the Vice Chair of the Whitney’s ownership of a tear gas manufacturing company.

The co-curators of this year’s Biennial, Rujeko Hockley and Jane Panetta, approached the project of this year’s Biennial with a full awareness of the exhibition’s legacy, recognizing in their curatorial statement that “fundamental to the Whitney’s identity is its openness to dialogue.” By assembling a multifaceted body of work that is forthright in speaking to issues roiling in America today, they have put together an exhibition in the spirit of productive dialogue, which neither shies away from this history nor provokes for provocation’s sake. And, featuring the work of 75 artists and collectives, the 2019 Biennial is one of the Whitney’s most diverse, with a majority of the artists being people of color, and half identifying as women. TIME spoke with Hockley and Panetta to discuss six works in this year’s Biennial that represent the breadth of the exhibition.

National Times, Agustina Woodgate

Born in Argentina and now based in Miami, Woodgate creates conceptual installations that function as visual allegories for sociopolitical problems. In a glaringly fluorescent room of the gallery, a row of clocks lining the walls is coordinated with an electrical interface on the opposite end of the room. Known as a “master-slave” configuration, this kind of system has been used since the Industrial Revolution to control time in schools and factories as a means of regulating the workday. “The idea is that all the slave clocks take their time from the master clock, which is itself synced to the atomic clock, so that all of these remain the same. But of course, over time they fall out of sync,” says Hockley. Woodgate has also attached sandpaper to the minute hands, which gradually scrapes away the numbers as the hands rotate. What began as a seemingly infallible system inevitably falls to entropy, rendering the clocks useless. “She thinks about the historic relationship with timekeeping and issues of labor and control,” Panetta says.

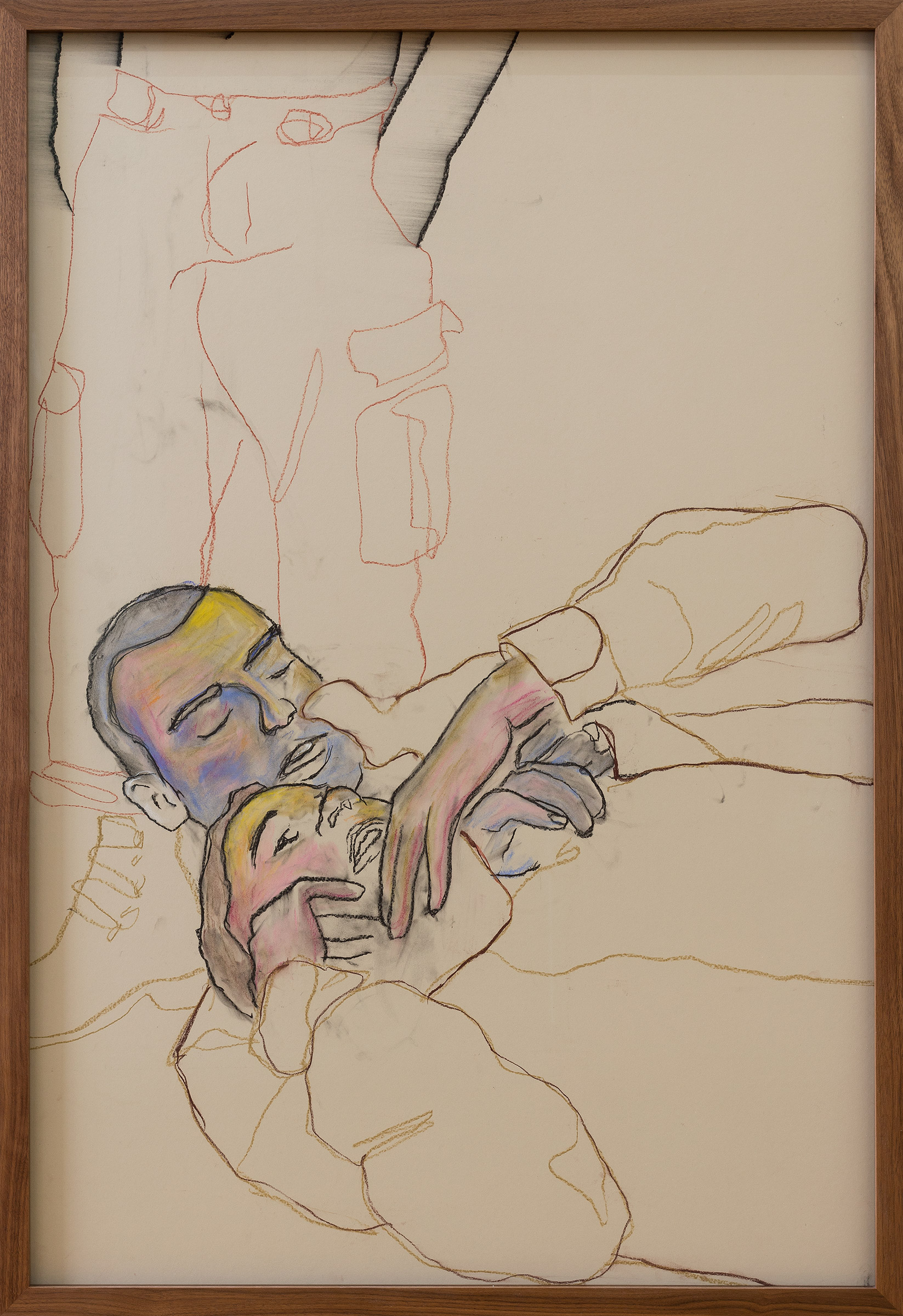

Suggested Occupation 4, Kyle Thurman

Suggested Occupation 4 is one of several figurative works by Kyle Thurman featured in the Biennial. In this series, Thurman takes images from newspaper and other media of archetypal depictions of men, frequently soldiers or athletes. Through his process of reproducing the image as a drawing, Thurman omits the surroundings, leaving the figures isolated in a field of color. The resulting image brings attention to the figures on their own, “highlighting the strangeness around masculinity and men’s bodies being in proximity to each other,” Hockley says. Without their context, previously unseen intimacies are made visible, as well as undercurrents of homoeroticism that go unacknowledged in typically masculine spaces.

Born Athlete American: Laurie Hernandez I, Jeanette Mundt

During the 2016 Olympics in Rio De Janeiro, the New York Times ran a series of photos dissecting the winning movements of the USA Women’s Gymnastics team frame by frame in a single image. Drawn to these photos, Jeanette Mundt, whose work often addresses the scrutiny of women’s bodies, created a series of paintings inspired by the photos. “I think at first she got really interested in the tension between there being such an emphasis on the strength and power of these gymnasts, and then simultaneously on their hair and makeup that needed to be so pristine and feminine,” Panetta says. Here, Laurie Hernandez’s balance beam routine is broken down from start to finish, bringing attention to her physicality to an almost anatomical degree. The technique of layering frames side by side also echoes, as Hockley points out, the 19th-century photographs of Eadweard Muybridge documenting the mechanics of animal motion. In the midst of this technical scrutiny, Mundt still pulls focus to Hernandez’s femininity, adding glitter to her bodysuit on the painting. “You can see they are kind of broken down into pieces already by the nature of the judgment that is passed on them, both the sanctioned judgment of the routine but also this other side of, ‘Do they look the part?’” Hockley says.

Ilustraciones de la Mecánica, Las Nietas De Nonó

Raised in rural Puerto Rico, sisters Lydela and Michel Nonó, who make up the performance duo Las Nietas De Nonó, use a mixture of theatrical performance and visual art in order to address themes of colonialism and race. This photo taken from a performance of their piece, Ilustraciones de la Mecánica, shows one sister as a doctor and the other as a patient who is being prepared for invasive surgery. Performed in silence and using organic materials like grated beets and vegetable leather, the sisters reenact what resembles a hysterectomy procedure. The performance addresses the history of forced sterilization of women in Puerto Rico sanctioned by the U.S. government, which persisted until the 1970s. During the span of the exhibition, they will stage three ticketed performances that will take place in the gallery.

The Villain, John Edmonds

Edmonds, a New York-based photographer, is conscious of the history of representation of black bodies in his medium. In images like The Villain, he subverts assumptions about identity. With a sensitivity to light, color, and tonality that makes his portraits exude a gentle warmth, and informed by the work of earlier photographers like Edward Steichen and Man Ray, Edmonds renders his subjects, many whom are queer, as icons in their own right. Both Hockley and Panetta remember being particularly taken by The Villain the first time they saw it. “It’s such a striking image in its composition, but also thinking about the title, calling something The Villain when it’s a young black man with a bandana over his face, evoking banditry—all of this happening simultaneously we found to be very interesting,” Hockley explained.

Donkeys Crossing the Desert, Lucas Blalock

Lucas Blalock’s surreal digital collage is one of the exhibition’s largest works, inhabiting a billboard facing the museum that is viewable from the galleries. To make his work, Blalock composes real world objects into a still life, which he photographs and then alters through digital manipulation. The results are humorous and uncanny, like the three donkeys seen here, which straddle the line between the real and the artificially rendered. Further toying with the already tenuous boundary between the digital and the real, Blalock created an augmented reality component to the billboard that can be viewed through a smartphone by downloading an app called “Donkey Business.” Some museum-goers may bemoan the integration of smartphone technology into the experience, but there is more to Blalock’s donkeys than sheer novelty. “It’s a really interesting inversion to the way we think about technology and our phones,” says Hockley. “We usually think of them as an impediment to paying attention to our surroundings.” But here, she says, Blalock seems to be saying, “This is how we live now, so let’s use that and let’s speak to it and not pretend it doesn’t exist.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Wilder Davies at wilder.davies@time.com