Warning: This post contains spoilers for Game of Thrones.

As the final season of Game of Thrones moves toward its conclusion, who’ll end up on the Iron Throne is not yet clear — but one thing is.

It’s now obvious that Lord Varys would now like to see Jon Snow rule. In the season’s fourth episode, “The Last of the Starks,” Varys made his case to Tyrion that, despite their long allegiance to Daenerys Targaryen, they ought to support Jon Snow instead.

Jon — who, the two advisers now know, is actually a legitimate Targaryen too — is temperamentally fit to rule, Varys argues, and the fact that’s he’s a man makes him more appealing to the aristocracy of Westeros. Being a man isn’t qualification alone, Tyrion replies, to which Varys has a quick rejoinder: “And he’s the heir to the throne, yes, because he’s a man.”

But, while Varys is right that Jon has a strong claim to the throne, if Westeros follows the real-world rules that have historically governed most European monarchies of the kind seen in the show, the reason is not just because he’s a man.

“On its face, the realm of Westeros is an absolute monarchy (the ‘Seven Kingdoms’) governed by a king (though for now a queen reigns),” writes Creighton University School of Law’s David P. Weber, in the article Legal Structures in A Game of Thrones: The Laws of the First Men and Those That Followed, which recently appeared in the South Carolina Law Review. He explains that Westerosi succession, at least in the Seven Kingdoms if not in regions like the Iron Islands, appears to follow the rule known as primogeniture: the right of the firstborn to inherit estates and titles. Most systems of primogeniture have historically favored sons, but not all.

“If it were absolute primogeniture, if Jon Snow were a woman, she would still have a superior claim because of who their parents were,” Weber tells TIME.

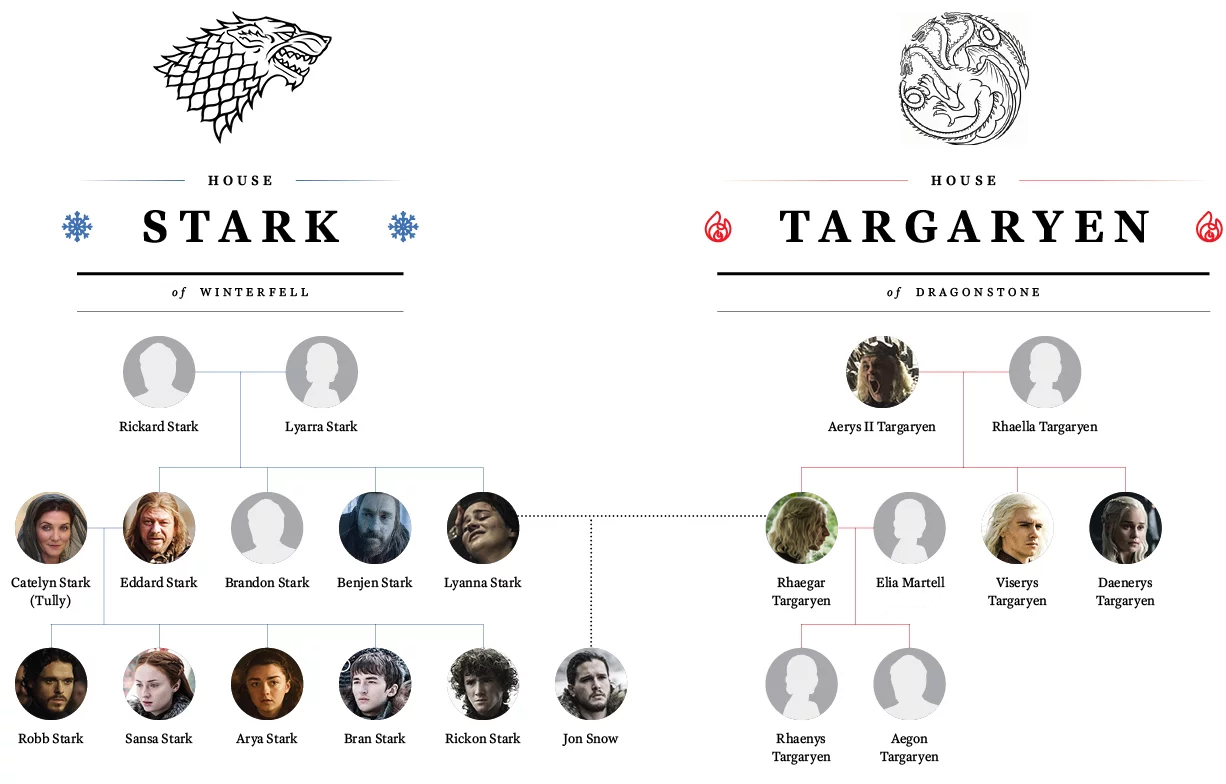

In other words, Jon’s claim would be stronger than Daenerys’ not primarily because of his gender but because his father, Rhaegar Targaryen, was the heir to King Aerys II Targaryen; Jon is the heir of the heir. Daenerys, meanwhile, though she is the only surviving child of the King, is Rhaegar’s younger sibling.

In fact, while the real British history that shows up in Thrones more commonly dates to the late medieval period, a good reminder of how this system works can be seen in the extremely recent past: primogeniture is the reason why Archie Mountbatten-Windsor, the firstborn son of Prince Harry, is seventh in line for the British throne. The line of succession goes through Prince William and all his children before it gets to William’s younger brother, Prince Harry, and subsequently to Harry’s children. In the Game of Thrones scenario, Jon Snow is like Prince George, the eldest son of Prince William, and Dany is Prince Harry, the younger sibling of the heir.

Modern British history also offers a parallel for the ways in which gender doesn’t have to be a deciding factor: Princess Charlotte, William’s daughter, would be called up before baby Archie, too. Britain’s rules of royal succession recently changed so as not to favor men, as the Succession to the Crown Act was amended. On Game of Thrones, the dominant form of primogeniture does seem to favor sons — though the show, at least until recently, hasn’t ruled out the possibility of women inheriting power.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

This system has wielded a strong influence on European history, Evelyn Cecil’s 19th-century treatise Primogeniture: A Short History of Its Development in Various Countries and Its Practical Effects explains.

When feudalism became a defining characteristic of European life, there needed to be a system by which local lords’ lands and titles could pass through the generations without going to war each time a powerful person died. These decisions had at times been decided by decree of the ruler on a case-by-case basis, but by the Middle Ages the eldest son became a default inheritor. Cecil argues — while admitting that primogeniture isn’t a foregone conclusion, as it’s not the only answer history has supplied to this problem — that the reason this system became so dominant was simply that the social order at the time was very unstable, so it behooved kings to give local lords what they wanted in order to keep them happy.

In the absence of both strong central power and a legal system that allowed for the common dispersal of estates through written wills, primogeniture was at least relatively reliable and a good way for lords to feel that it was worth preserving and consolidating their holdings to pass on to their children. Later, as royal power increased and the social order became more stable, the system was allowed to continue as long as the king was strong enough not to be threatened by major families holding onto their estates.

“Primogeniture of the modern type first became recognisable in Europe about the time of King Henry I of England [the 12th century],” Cecil writes, “when the descent of [estates] to the eldest son, if he was alive, began to be accepted; but if he had predeceased his father, leaving descendants, it was yet approximately a couple of centuries before his descendants obtained a settled priority over an elder representative of the previous generation. In England, this point was determined by the time of Henry III, and Edward I’s decision in 1292 of the controversy between Bruce and Baliol probably gave a fresh impetus to the course the stream was taking.”

As Weber notes in a footnote to his paper, glimpses of the line of succession that appear in George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire books indicate that this system prevails in his fantasy world. For example, the story’s lore holds that before the time of A Game of Thrones, a Great Council had been called at least once to declare that the throne would pass to a younger child of the King rather than the child of the oldest child, implying that primogeniture was the rule to which a case like that was an exception. (The books imply that a similar declaration might affect Jon and Dany, if her brother Viserys was declared the heir before Jon was born and after Rhaegar died, but that complication is glossed over on the show.) Primogeniture is also why, in that world, the question of whether a son is legitimate matters so much.

But, Weber says, just because Jon’s claim is strong, that doesn’t mean Daenerys would be out of luck if this were a real historical monarchy. After all, primogeniture may be common, but it’s not the only way kings and queens throughout history have taken their thrones.

“Even though you might have competing claims between Daenerys and Jon,” he says, “there very well might be a good argument that, one, that she’s going to take it by conquest or two, even if he has the superior claim, he’s already bent his knee to her, so there’s a decent legal argument that he’s already abdicated his right.”

Abdication is certainly something that happens in real life — examples range from the brief reign of Edward VIII to Japan’s recent change of Emperor — and Weber says that, as far as his own legal studies suggest, the fact that Jon didn’t know his true identity when he knelt wouldn’t necessarily make a difference.

“He gave up whatever claim he had as King in the North to follow her. I think that’s essentially what an abdication is, a relinquishment of his legal rights,” he says. “I think people typically when they do that, they understand the consequences, legal and social. I can’t think of anyone [in history] who came back and said ‘Whoops, I want a mulligan.'”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com