Historians of the environmental movement often locate the conservation movement’s genesis in mid-19th-century literature, most commonly invoking writers such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau and John Muir. After Emerson composed a book titled Nature in 1836, a new, mystical religious and philosophical movement called transcendentalism began to emerge in Boston, Emerson its founder, with the help of Thoreau and others. Believing that a direct experience with the divine could be attained through intimate interaction with nature, both became known as naturalists in what was a new, highly romanticized, and particularly American version of naturalism.

While Emerson and Thoreau were paving fresh intellectual ground in the East, the artist George Catlin (who was unconnected to the Transcendentalist movement) was traveling out west documenting the last of the “wild” Indian tribes, becoming famous for the hundreds of paintings that are now his legacy and for beginning a national dialogue on the need for national parks. He published several books, among them the classic Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Condition of the North American Indians in 1841. In the book, Catlin lamented what he believed was the beginning of the extinction of the buffalo and the tribes who depended on them. He proposed that the U.S. should create a “Nations’ park containing man and beast, in all the wild and freshness of their nature’s beauty!” Catlin’s work was influential and widely acclaimed, and while the idea for a national park was not yet taken seriously, a growing national angst about modernity made conditions ripe for it by the early 1870s.

The national park system has long been lauded as “America’s greatest idea,” but only relatively recently has it begun to be more deeply questioned. In his 1999 book Dispossessing the Wilderness: Indian Removal and the Making of the National Parks, Mark David Spence delivered a long-overdue critique that linked the creation of the first national parks with the federal policy of Indian removal. Spence points out that the first so-called wilderness areas that had been deemed in need of preserving were not only and in actuality Indigenous-occupied landscapes when the first national parks were established, but also that an uninhabited wilderness had to first be created. He examines the creation of Yellowstone, Glacier and Yosemite National Parks in particular to illustrate the way the myth of uninhabited virgin wilderness has for more than a century obscured a history of Native land dispossession in the name of preservation and conservation and serves as the foundation of the environmental movement.

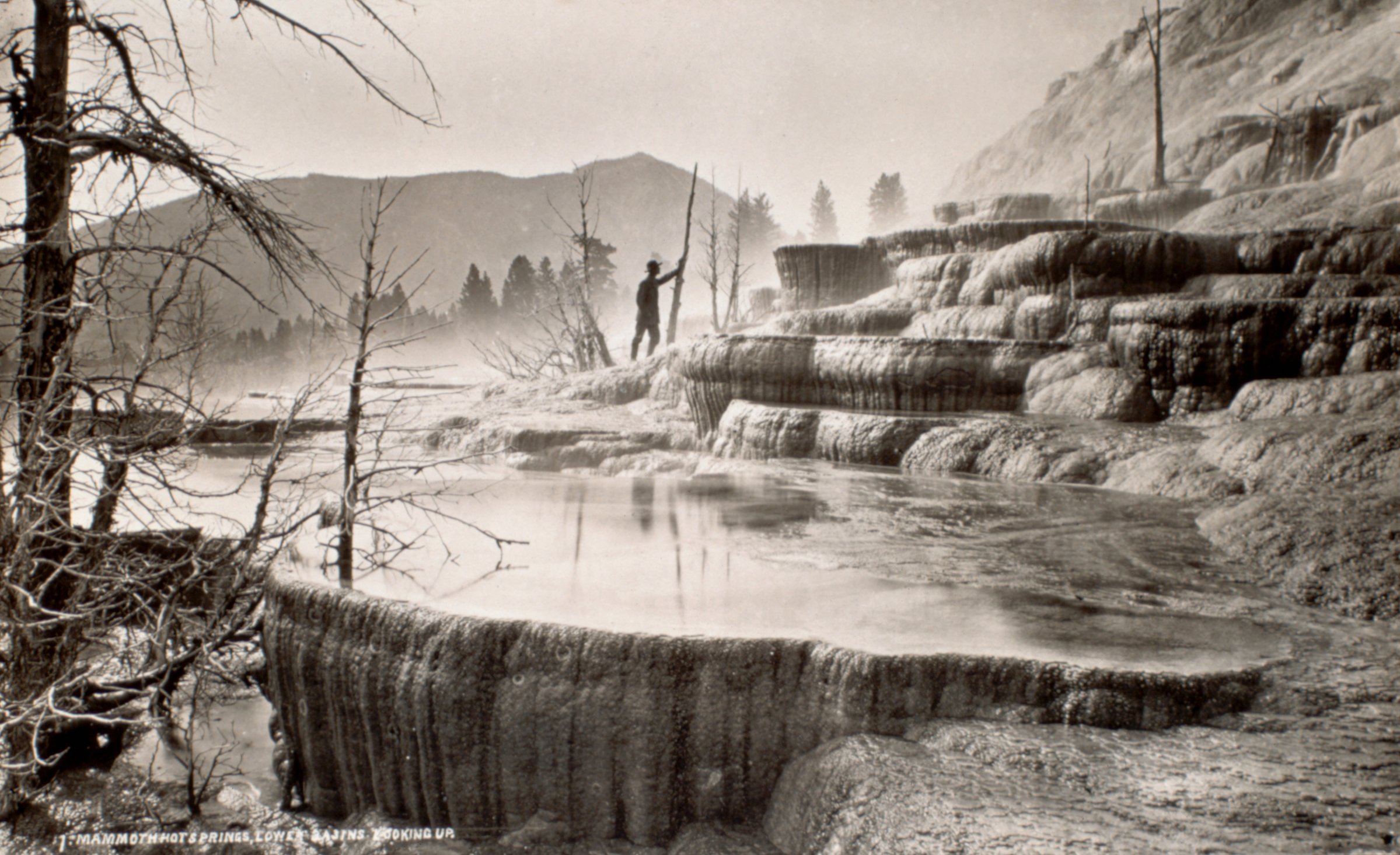

The creation of Yellowstone as the first national park is instructive for understanding how the language of preservation evolved over time. What is today Yellowstone National Park (which lies predominantly within the northwest corner of Wyoming and slightly within Montana and Idaho) was originally the territory of numerous tribal nations, including Shoshone, Bannock, Crow, Nez Perce and other smaller tribes and bands. The treaties of Fort Bridger and Fort Laramie in 1868 ceded large tracts of land to the U.S. and created separate reservations for the tribes but retained the right of the continued use of the ceded lands for hunting and other subsistence activities. Although early settlers had claimed the Indians avoided the Yellowstone area due to superstitions about the geysers, they in fact had long used the lands, a rich source of game and medicinal and edible plants, for spiritual ceremonies and other purposes.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

After the park’s establishment in 1872 the Indians continued to frequent the area, especially since limited reservation land and government food rations were insufficient to feed the people, and the threat of starvation constantly loomed. According to Spence, Yellowstone, with its mesmerizing geysers and otherworldly geologic formations, was set aside initially not in the interest of preserving wilderness but as a “wonderland” for its unique natural features — an ideal tourist attraction. But the threat of private development such as mining interests, timber exploitation and railroads combined with fears about the depletion of game, fish and timber, changed the government’s rationale for the park. By 1886 the Department of Interior’s stated purpose for the park’s existence was the preservation of the wilderness (animals, fish, and trees), to be enforced by the military, which was already aggressively pursuing resistant Indians throughout the Plains.

Anxiety about hunting in the park over the next few years led to the passage of the Lacey Act in 1894, a law prohibiting all hunting within park boundaries, including Indian hunting — in direct violation of treaty protections. A legal challenge to the law resulted in the U.S. Supreme Court case Ward v. Race Horse in 1896 in which, as Spence contends, the court ruled that the creation of Yellowstone National Park and the Lacey Act effectively signaled Congress’s plenary authority to nullify Indian hunting rights at will, at a time when both judicial and congressional decisions persistently eroded Indian rights. Race Horse was overruled by the Supreme Court in a 1999 case brought by Minnesota’s Mille Lacs Band of Chippewa Indians, but in a separate 2016 case a Wyoming state court rejected the Crow’s treaty right to hunt on federal lands within the state. That case is still pending in a state appellate court. These cases demonstrate the contradictions in law when state and federal law conflict relative to Indian treaty rights.

The lingering result of the Yellowstone story is that coded within the language of preservation, “wilderness” landscapes — always already in need of protection — are, or should be, free from human presence. But this logic completely evades the fact of ancient Indigenous habitation and cultural use of such places. In Spence’s words, “the context and motives that led to the idealization of uninhabited wilderness not only helps to explain what national parks actually preserve but also reveals the degree to which older cultural values continue to shape current environmentalist and preservationist thinking.”

In other words, the paradigm of human-free wilderness articulated by early preservationists laid a foundation for the 20th-century environmental movement in extremely problematic ways. When environmentalists laud “America’s best idea” and reiterate narratives about pristine national park environments, they are participating in the erasure of Indigenous peoples, thus replicating colonial patterns of white supremacy and settler privilege.

Excerpted from As Long As Grass Grows: The Indigenous Fight for Environmental Justice from Colonization to Standing Rock by Dina Gilio-Whitaker (Beacon Press, 2019). Reprinted with permission from Beacon Press.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com