The knotted rope and the fire hose, the lunch counter and the poll tax — the most notorious aspects of America’s ignominious record on race are well known, but they are not the whole story. One chapter has remained largely hidden for decades: how the United States Army, during the early years of the civil rights movement, dealt with the crucible issues of race and capital punishment. Not well, it turns out.

In the years between 1955 and 1960, all eight white soldiers who were condemned to death, each of them a murderer, saw their sentences commuted by the Eisenhower Administration, the federal courts or the Army itself. Eventually they all won parole too, and returned home to the embrace of their families and loved ones.

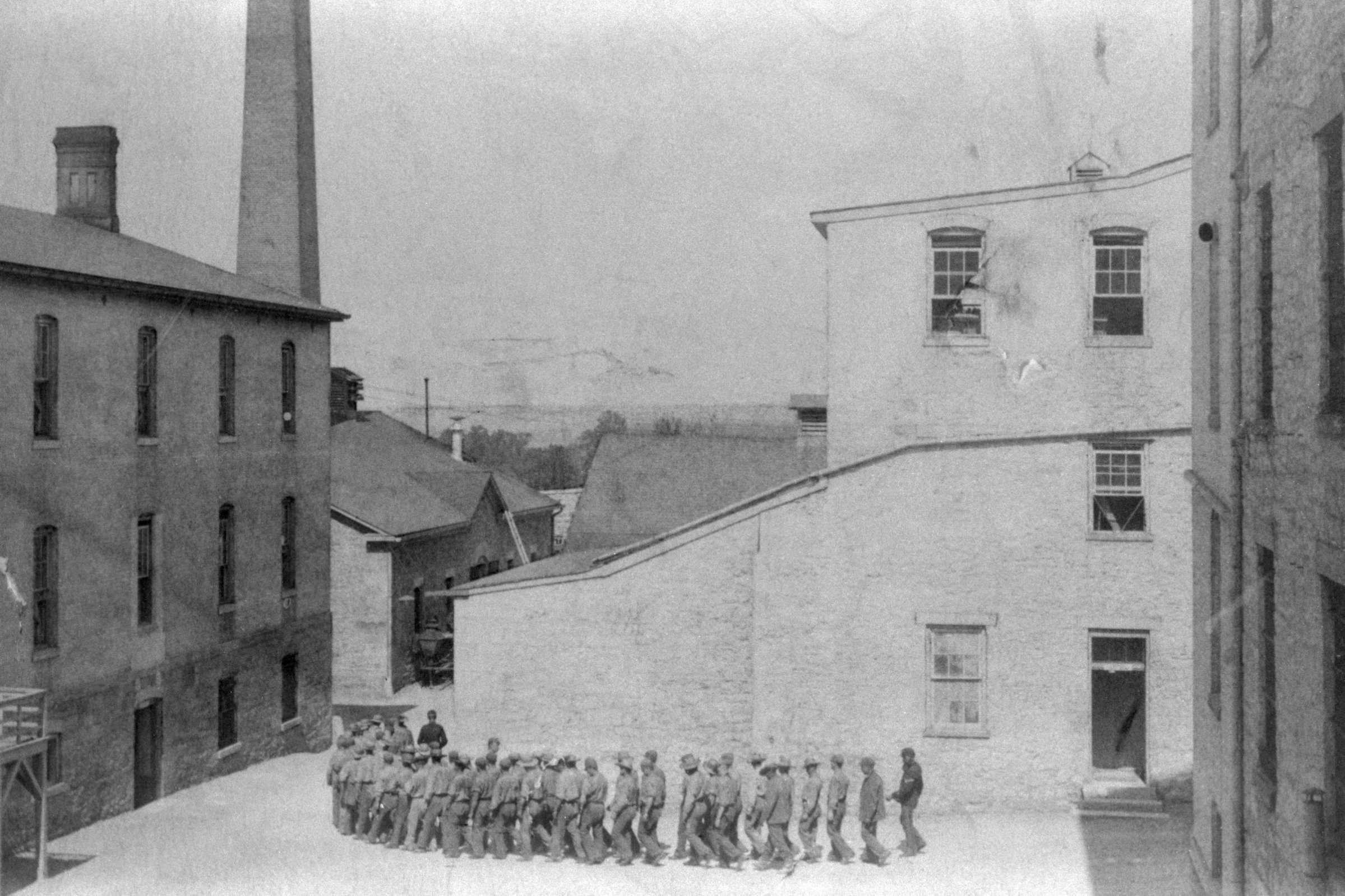

In contrast, the eight convicted murderers who were hanged by the military — summoned from death row cells in the sub-basement of Fort Leavenworth, Kans., and marched to the top of a wooden gallows — were all black.

The white men benefited from influential Washington politicians, the Army brass, astute capital defense attorneys, public outcries and even a sympathetic national press. Government records show how Washington’s elite often bent backwards to find a reason to spare their lives. One white soldier drowned an Army colonel’s only daughter, 8 years old, in shallow waters outside their base near Tokyo; yet he went home. Another raped and slashed to death a 5-year-old local girl in Okinawa: he too was set free.

Their black counterparts were seldom recognized, and never singled out for any great lobbying effort to spare their lives. No Washington insiders rushed to their defense; no press or public championed their cause. Generally, the most encouragement they could draw would be in the form of a pitiful hand-scribbled letter from their often-semi-literate mothers, pleading for mercy. “I am begger for his life,” Mrs. Gentry Collier of Chattanooga, Tennessee, wrote the Eisenhower White House. “…he was a good boy both white and colored love him he ant never have ben in trouble tell he was in the army” (sic all).

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

The last doomed soldier from that era turned out to be a young black soldier from southern Virginia. He was the ninth black soldier executed in that era and, it would turn out, would be the last soldier executed by the Army to this day. Private First-Class John Arthur Bennett, a descendant of tobacco-plantation slaves, was accused and found guilty of raping and assaulting a young white girl. The Army sentenced him to death, rape being then on the Army books as a capital crime. He was 18 when taken into custody in then-Occupied Austria, and he languished for six years on the army’s death row cellblock, a metal-and-concrete chamber deep in the bowels of the main prison at Fort Leavenworth, what many called “The Castle.”

By early 1961, when his case rolled into the start of the Kennedy Administration, a black civil rights attorney from Bennett’s home community took up his defense in hopes the country’s new commander-in-chief—a Democrat, a Catholic, a liberal—would step in and save this final life. In his plea to the President, he stressed that “a fundamental principle of an honest judicial system must be equal justice for all,” and cited the fact that white soldiers had been granted mercy.

But Kennedy was unmoved. He resisted taking up the matter of Private Bennett, and preferred to let the earlier Eisenhower decision stand that Bennett be put to death. Kennedy in those early months of his new administration had just barely won the White House, and realized politically that his very thin margin was boosted largely with white voter turnout in the Southern states. Nor was the new young president affected by pleas from some in his New Frontier administration who opposed capital punishment or last-minute telegrams from the victim and her parents urging that Bennett live.

Still Bennett implored Kennedy to save him. He had already outlasted two stays of execution. New evidence showed he suffered from a mental disorder and also suffered from epileptic seizures throughout his life, and that he may have been in the middle of an episode at the time of the assault. The young soldier and his small-town attorney continued to hope Kennedy would change his mind and commute this last death sentence, and with the presidential pen strike a major blow against the long racial history of Army injustice.

From his cell deep below the Castle, Bennett’s eyes desperately followed the prison clock as the hours drew down on April 12, 1961. Would be die at midnight too? Or would the Army’s disgraceful record of sparing white soldiers and executing only black troops at last come to an end?

They came for him, in the end. Today, the prison has long been torn down and the Army has not hanged a soldier since then. But little else has changed. A new modern Army death row currently houses four soldiers condemned to die. Three are men of color.

Richard A. Serrano is the author of Summoned at Midnight: A Story of Race and the Last Military Executions at Fort Leavenworth, newly released by Beacon Press.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com