George Gleig had seen thousands of soldiers in battle, but he had never seen any perform more disgracefully than the Americans assigned to defend Washington in the summer of 1814. “No troops could behave worse than they did,” wrote Gleig, an officer with a British force attacking the American capital. “The skirmishers were driven in as soon as attacked, the first line gave way without offering the slightest resistance, and the left of the main body was broken within half an hour after it was seriously engaged.” The British hadn’t dreamed that their assault would proceed so swiftly; they had barely engaged the defenders before the path to the city lay wide open.

The British commander, General Robert Ross, sent a flag of truce from the edge of Washington. But the bearer of the flag was fired upon from a window of a house, and his horse was killed beneath him. “You will easily believe that conduct so unjustifiable, so direct a breach of the law of nations, roused the indignation of every individual, from the General himself down to the private soldier,” George Gleig continued. “All thoughts of accommodation were instantly laid aside; the troops advanced forthwith into the town, and having first put to the sword all who were found in the house from which the shots were fired, and reduced it to ashes, they proceeded, without a moment’s delay, to burn and destroy every thing in the most distant degree connected with the government. In this general devastation were included the Senate-house” — the Capitol — “the President’s place, an extensive dock-yard and arsenal, barracks for two or three thousand men, several large storehouses filled with naval and military stores, some hundreds of cannon of different descriptions, and nearly twenty thousand stand of small arms.”

A spirit of righteous retribution moved the British in their sack of Washington, for earlier in the war American troops had gratuitously torched British government buildings in York, Canada. “All this was as it should be,” George Gleig said of the British reprisal. “And had the arm of vengeance been extended no farther, there would not have been room given for so much as a whisper of disapprobation. But unfortunately it did not stop here. A noble library, several printing offices, and all the national archives were likewise committed to the flames, which, though no doubt the property of government, might better have been spared.”

Years later Gleig recalled the awesome spectacle of Washington afire. Night was falling as the last of the British regiments marched into the city. “The blazing of houses, ships, and stores, the report of exploding magazines, and the crash of falling roofs informed them, as they proceeded, of what was going forward. You can conceive nothing finer than the sight which met them as they drew near to the town. The sky was brilliantly illumined by the different conflagrations; and a dark red light was thrown upon the road, sufficient to permit each man to view distinctly his comrade’s face. Except the burning of St. Sebastian’s” — in Spain during the Peninsular War — “I do not recollect to have witnessed, at any period of my life, a scene more striking or more sublime.”

The burning of Washington made Henry Clay look a fool. He had spearheaded the campaign in Congress in favor of the war against Britain and predicted a rapid victory. His drumbeating had started as soon as he entered the House of Representatives in 1811, when he earned the unprecedented — and never repeated — distinction of being made speaker of the House on his first day in the chamber. American grievances against Britain dated to the Revolutionary War. Britain had been slow to honor the treaty that ended that war, retaining posts near the Great Lakes, obstructing American commerce, and generally according the United States little of the respect due the independent nation America had become. The troubles escalated when war broke out between Britain and France in the early 1790s. American merchants and shipowners argued that they ought to be able to trade with both countries, since America was a neutral. But neither Britain nor France bought the argument, even as each continued to purchase the goods the Americans were selling, while trying to prevent the other from doing so. British ships seized American vessels bound for France and confiscated their cargoes; French seized American ships bound for Britain.

The American government complained, although the direction of the complaints depended on which party held power. The founders had uniformly decried parties as baleful manifestations of the selfish opportunism that had characterized British politics and prompted America’s bolt from the empire; they prayed their infant republic would be spared. But the new federal government was scarcely up and running before parties began to form, and the first divisive issue was the European war. Thomas Jefferson looked favorably on France, contending that revolution was usually a good thing and that France, having aided America in America’s hour of need, deserved American support now. A faction, then a party, of like-minded Francophiles coalesced around Jefferson and called themselves Republicans. Alexander Hamilton preferred Britain, citing ties of commerce and cultural affinity and detesting revolution on principle. American Anglophiles followed Hamilton and called themselves Federalists.

When the Federalists were in power the finger of American blame for ship seizures pointed at France. Indeed the Federalist administration of John Adams fought an undeclared naval war against France over the issue. When the Republicans took charge, Britain bore the brunt of American anger. The administration of Thomas Jefferson attempted diplomacy, then an embargo of American foreign trade, to end the seizures. Neither worked, and the seizures continued into the administration of Republican James Madison, who held the presidency when Henry Clay became House speaker.

A second issue intensified American anger at Britain. The British navy was desperate for seamen, and its officers had orders to man their vessels by any means possible. Service in the British navy was notoriously hard, and British sailors were chronically tempted to jump ship. Some did so in American ports, where British craft resupplied, and disappeared into the wharf-side populations. Not infrequently they then signed on with American merchantmen. British officers, alert to the practice, intercepted American vessels when they could and reclaimed the deserters.

The searches and seizures alone rankled Americans, as violations of American sovereignty. Even more infuriating was the British habit of seizing sailors who had never been in the British navy, on specious claims that they had been. This was nothing less than kidnapping and was condemned by Americans as intolerable.

The British provocations grew more egregious over time. In 1807 a British warship fired on an American navy vessel, the Chesapeake, within sight of the Virginia shore. The commander of the British vessel had called for the Chesapeake to stop and allow a British search party to board. The American commander refused, and the British officer ordered his gunners to blast a broadside into the unready American ship. Three Americans were killed and more than a dozen wounded, including the commander.

The attack outraged American opinion. Americans were shrewd enough to realize that the owners and captains of merchant vessels were making a gamble when they put to sea against the British; sometimes the gamble paid off and sometimes it didn’t. But an attack against a ship of the U.S. navy was an affront to the entire country.

Still another issue angered Americans toward Britain. From bases in Canada, British traders provisioned Indians living in the American Northwest. The provisions included weapons some of the tribes used to attack American settlements and kill American citizens. Westerners (in particular) resented the British role in the violence, and many demanded that Canada be seized and the British evicted from their last North American redoubt.

Henry Clay was one of those Westerners, by adoption. His birthplace was Hanover County, Virginia, and his earliest memories included the looting of his boyhood home by British soldiers during the Revolutionary War. The image would stick in his head as he grew older and dispose him to think the worst of Britain.

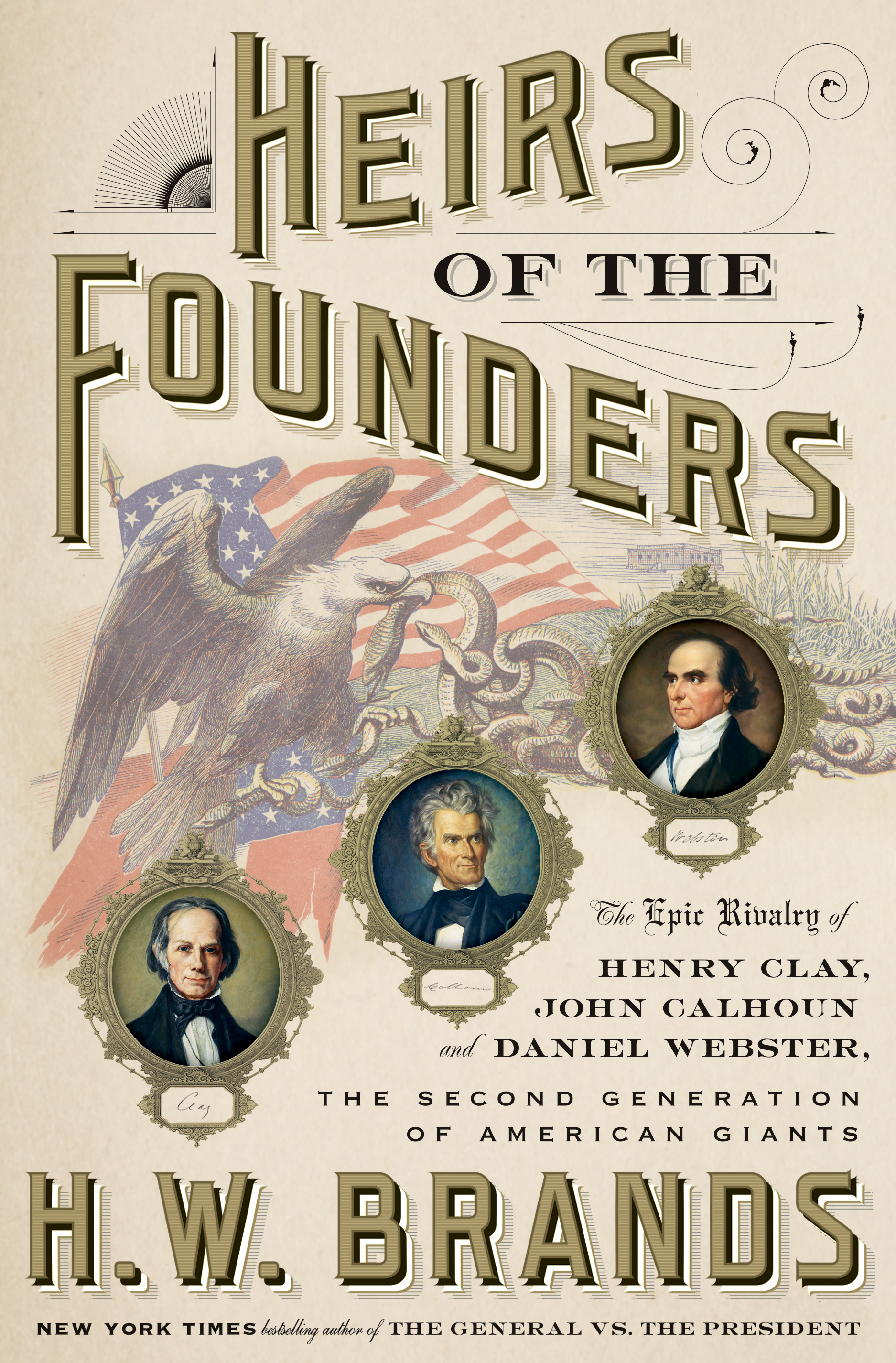

From the book Heirs of the Founders: The Epic Rivalry of Henry Clay, John Calhoun and Daniel Webster, the Second Generation of American Giants by H. W. Brands . Copyright © 2018 by H. W. Brands

Published by Doubleday, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com