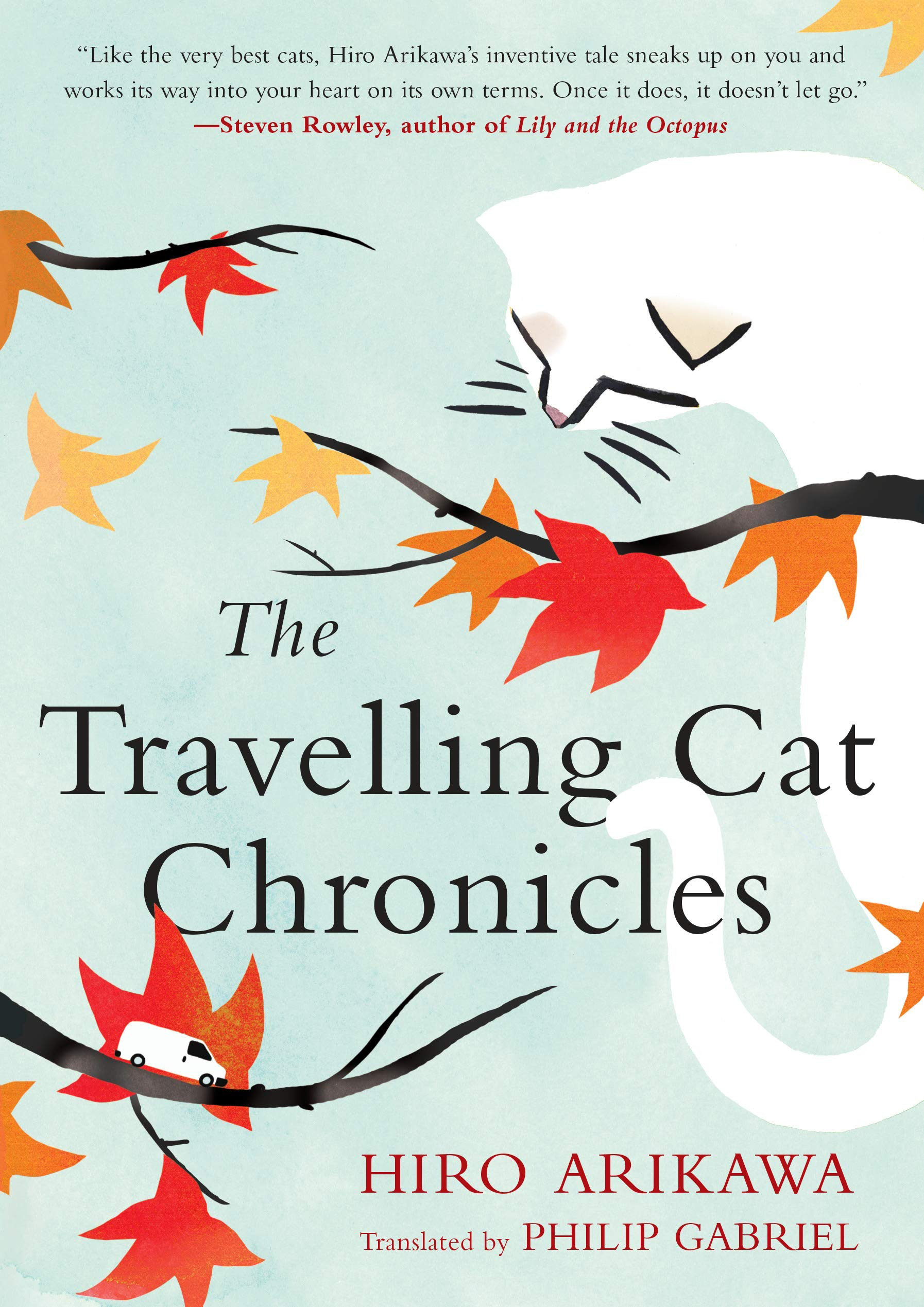

Whenever I’m reading a hardcover cat-related book in public–especially one featuring a cat who talks–I always remove the dust jacket. Wouldn’t want anyone to think I’m one of those ladies. While the “cat lady” stereotype endures, the reality is that there are secret, and sometimes not-so-secret, leagues of men who are just as crazy about them. The central character of Hiro Arikawa’s winsome and bittersweet novel The Travelling Cat Chronicles–a best seller in Japan, now translated into English by Philip Gabriel–is one of those men. Satoru loves cats in general and one cat in particular, a former stray with an auspiciously crooked tail whom he names Nana.

Nana himself, in a peppery interior monologue, tells the story of the duo’s first meeting: He has been sleeping on the hood of Satoru’s silver van, parked outside his apartment building; the young man notices and tries to coax him with a bit of chicken. “You think you’ll get all friendly with me by doing that?” the soon-to-be-named Nana observes incredulously. “I’m not that easy. Then again, it’s not often I get to indulge in fresh meat–and it looks kind of succulent–so perhaps a little compromise is in order.”

The dog lover’s bookshelf, stretching from J.R. Ackerley’s My Dog Tulip to John Grogan’s Marley and Me and beyond, may be long. But there are nearly as many cat book genres as there are types of cats, too: mysteries starring cats, memoirs about people’s lives with cats, guides to figuring out how to make our cats’ lives better. The mind of a cat remains essentially unknowable, no matter how many cat books a cat person reads, but Arikawa clearly knows cats as well as any human can. From the outset they must make their disdain for humans clear, only to give in and accept the food already. Because what cats feel, Arikawa knows, is not really disdain but a kind of cautious custodianship of their love. It’s not something they can give away to just anybody. That understanding of the wariness of feline affection–and its ability to grow, over time, into a thrumming force as deep as a throaty purr–drives this fleet, funny and tender book.

Shortly after that first meeting, Nana truly becomes Satoru’s cat, settling quickly into the rhythms of domestic feline contentment. But fate intervenes, and he and Satoru strike out on a journey that illuminates Satoru’s past and the friendships–human and feline–that helped shape him as an adult.

Satoru takes Nana to a grave site along the way, prompting some observations about the differences between the ways humans and animals view death. The cat’s way, as Nana explains it, could free some humans from lifelong angst. “When an animal’s life is over, it rests where it falls,” he notes. “If you have to consider what’s going to happen after you die, life becomes doubly troubling.”

The story Arikawa tells is ultimately joyous, though it’s brushed with melancholy. No one gets through life without sadness, as any human who has lost a cat, and any cat who has lost a human, knows. This is a gentle book about the way cats bear witness to our lives, weaving through and around our days just as readily as, in moments of spontaneous affection or plain old hunger, they weave around our legs.

Are cats born with strong, distinct personalities? Or do their personalities take shape only when they’re exposed to humans? Not even a human as perceptive as Arikawa can answer those questions definitively. But her book stands out within the world of cat literature even so, and it’s a world worth exploring. Arikawa examines loyalty and the nature of belonging–of people belonging to animals, and the other way around. Her book gives in to emotion without slipping into sentimentality. And like cats themselves, it walks with dignity. So you can read it with the dust jacket on.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com