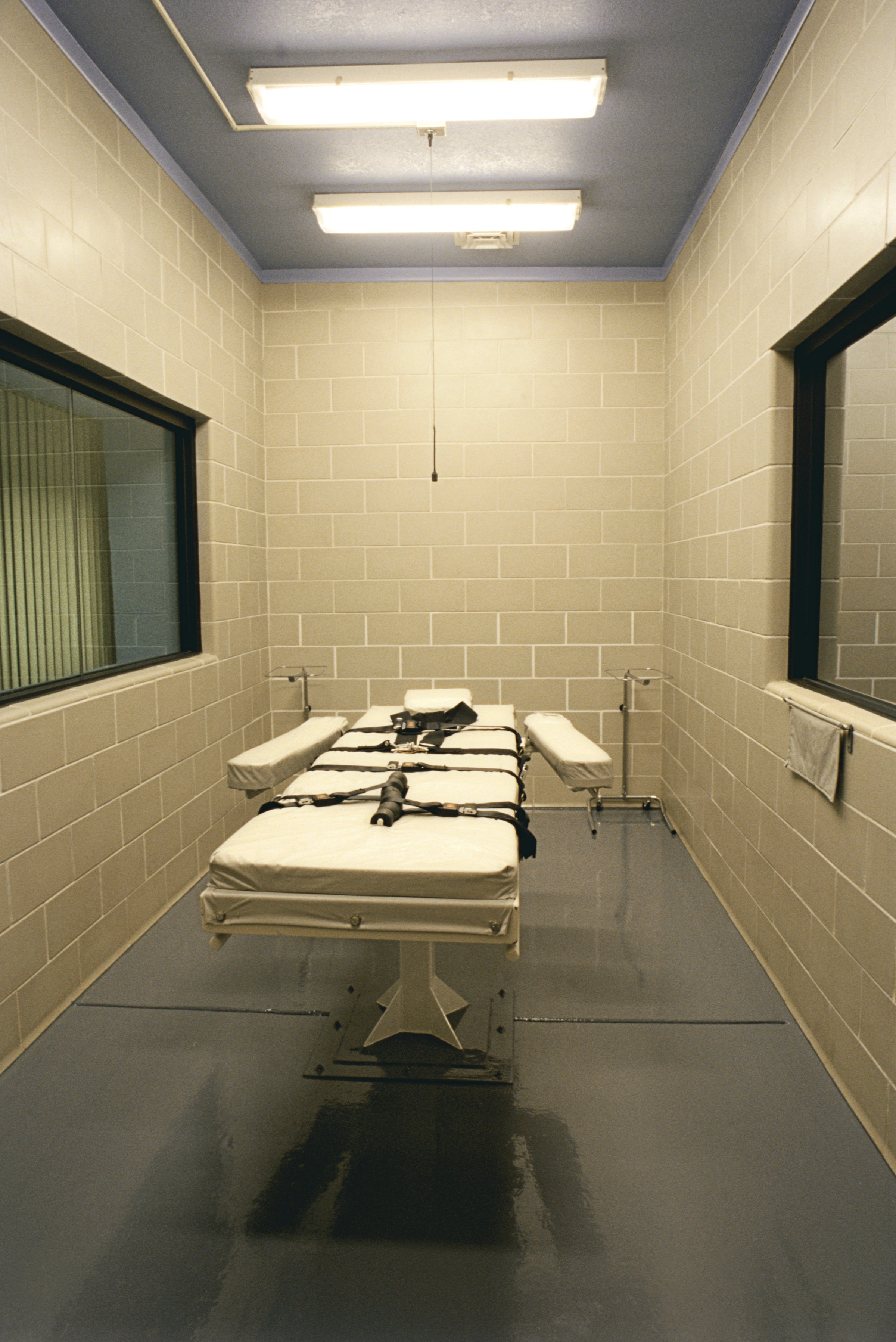

Let’s say you’re about to be executed. Let’s say you’re given a chance to say some final words. What are the odds you would say, “Go Raiders,” or “I could sure go for some beef stew and a chicken bone,” or “For what? You motherf*****rs haven’t paid any attention to anything I’ve said for the last 22-1/2 years…”? In the alternative, what are the odds that you might say, “I wish to apologize to the people I’ve hurt and I ask their forgiveness, I don’t deserve it but I ask for it,” or “I know I took someone very precious to you…I would pay it back a thousand times to bring back your loved ones…”?

The answer may depend on where you grew up. If you’re from the North or West, you’re likelier to stay badass till the end; if you’re from the South, you’re likelier to show some remorse. The bad guys who talked football, chicken and trash were from Arizona, Ohio and Ohio; the ones who showed some curtain-call decency were from Alabama and Texas.

The last second good manners of Southerners going to their deaths after a life of the worst kind of crimes was documented in a new paper published in Sage Open, titled, straightforwardly, “Honor on Death Row.” Its curious findings tell us a lot about not just the exceedingly specialized population of condemned men, but about the curious duality of human morality as a whole.

The study, conducted by Judy Eaton, a professor of criminology and law at Wilfred Laurier University in Ontario, surveyed the last words of 279 white males, looking for six qualities: an apology, an acceptance of responsibility, a request for forgiveness, an expression of regret, a sense of remorse and a general phrasing that suggested earnestness. Consistently, Eaton found, it was the Southerners who did better than the Northerners, and the reasoning has to do with what she called the “honor culture” of the Old South.

Honor cultures are built on highly codified, Kabuki-like courtesies and by-your-leaves, which themselves grow from a finely honed sense of the kinds of things that give offense and the serious price that may be paid if you cross that boundary. In the case of the South, Eaton and earlier researchers believe that honor culture goes all the way back to the herding populations of the Scots and Irish who were among the first to settle the region. When you’re a herdsman, everything depends on respecting territory and grazing grounds and you’d best have a good excuse and a believable apology ready if you don’t stay on your side of the line. Once a mind-your-manners ethos gets encoded in the social genome, it doesn’t go away.

Not everyone is invited into the honor culture. In the Old South, it was a white males only club, which is why Eaton eliminated 231 non-whites and nine women from her executed sample group. The variable she was investigating, at least in this study, was geography alone.

OK, most folks don’t have a lot in common with the moral monsters who usually wash up on death row. But the fact is, we’re all born with a basic moral software that evolved over millions of years, got more and more complex as our brains did and was absolutely essential if a highly social species like ours was going to survive. Ethicists and behavioral scientists refer to that fundamental set of behavioral guidelines as moral grammar. As with real grammar, its rules are often broken; as with real software, it can become corrupted.

A lot of things can cause that breakdown: life experience, deprivation, poverty, psychological disorders. All of those can be turbo-charged by nothing more than a mean streak. Not every poor or deprived person winds up on death row, after all, and moral grammar does include a component of accountability: sometimes you get in trouble because you’re just a nasty bastard and make bad choices. But good choices—and good manners—can be become permanent habits, one more reason we have survived as a species.

I’m put in mind of a young, southern officer I met during a visit to the aircraft carrier USS Eisenhower. The difficulty of navigating the narrow corridors of all Naval vessels is simplified a bit by the rule that a lower-ranking person must always yield to a higher ranking person approaching from the other direction. The officer I spoke to admitted that that became hard for him when he began serving with lower-ranking women.

“I was brought up to stand aside and let a woman pass,” he told me. “It just feels wrong not to.”

Archaic? Maybe. Out of step with our supposedly sexually egalitarian military? Sure. But sweet too—you have to admit it’s sweet. And his mother would probably be proud.

Such tiny grace notes occur all the time, every day, and help us—in our own flawed and fractious way—get along. That is no bar to the worst of us coming to an ugly end. But the fact that, even as that end plays out, a flicker of our better tendencies sometimes resurfaces, provides a small bit of hope.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com