President Donald Trump announced on Monday that he’s nominating Brett Kavanaugh, a D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals judge, to replace retiring Justice Anthony Kennedy on the Supreme Court. But that announcement is only the beginning for Kavanaugh.

Before he can serve on the court, he first needs to be confirmed by the Senate — where Democrats have vowed to put up a fight to block Trump’s second nominee to fill a seat on the nation’s highest court.

What the Constitution says about that process (in Article II Section II) is simply that the President “shall nominate, and by and with the advice and consent of the Senate.” Ironically, considering the polarized political climate today, a big reason why the Founders bestowed on the Senate the responsibility for “advice and consent” was to keep the process removed from the passions of the people, as the Senate’s members were chosen at the time by state legislatures. And, though hearings aren’t specifically required by the Constitution, the Senate has given Supreme Court nominees a hearing consistently since 1955.

The 49 Democratic Senators can’t block Kavanaugh alone but, as TIME reported last week, they are hoping to get Senators Susan Collins (R-ME) and Lisa Murkowski (R-AK) to join in their effort. Still, pundits are confident about Kavanugh’s chances. After all, outright rejections of Supreme Court nominees are rare in modern U.S. history — though they do happen.

Here’s a look at five red flags Senators have raised that derailed Supreme Court nominations in the past:

1. The Nominee’s Record Is Hiding Something

According to the Senate’s Historical Office, between 1894 and 1968 the Senate only rejected one nominee to the Supreme Court: North Carolina judge John Parker, Herbert Hoover’s nominee to replace Edward Sanford, on May 7, 1930, by a 39 to 41 vote.

The Parker case is an early example of how interest groups can doom a Supreme Court nominee’s chances at confirmation by doing the work of digging up controversial statements in his or her past and bringing national attention to those matters.

General resentment of Herbert Hoover, who was blamed for the Great Depression, was at play with Parker, as well as “the deep controversy of Liberalism v. Conservatism,” as TIME put it. In that atmosphere, outside groups played a key role in finding damning skeletons in Parker’s closet. Labor activists pointed to an opinion in which he upheld a “yellow-dog contract,” in which an employee promises not to join a union as a condition of employment, and the NAACP found a statement he made during his 1920 campaign for Governor of North Carolina, in which he said that the participation of African-Americans in politics “is a source of evil and danger to both races.”

The work of these outside interest groups “torpedoed” Parker’s confirmation, says Barbara Perry, the Director of Presidential Studies at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center of Public Affairs, who spoke to TIME as part of a presidential-history partnership between TIME History and the Miller Center.

2. The Nominee Isn’t Qualified

Two later nominees rejected after their past decisions were questioned were Clement Haynsworth and George Harrold Carswell, both nominated by Richard Nixon and both denied seats in what was seen as an indictment of both his Southern Strategy — his picking Southern judges was seen as part of his appeal to Southern voters — and his competency as President.

For Carswell, his past statements relating to civil rights helped doom his chances; for example, in a 1948 speech he had said that, “Segregation of the races is proper and the only practical and correct way of life.” But his record wasn’t the only problem. Senators also felt that Nixon weighed his political strategy over their qualifications. “The rejection actually reflected a widespread conviction that Carswell simply did not measure up to the stature of men the Senators wanted to see added to the Supreme Court,” TIME noted. “Even many Southerners felt insulted that Nixon had chosen Carswell to represent them.”

The next month, the Senate would confirm Nixon’s third nominee 94-0: Harry A. Blackmun, who would go on to write the opinion for the majority in Roe. v. Wade.

3. The Nominee’s Politics Are “Wrong”

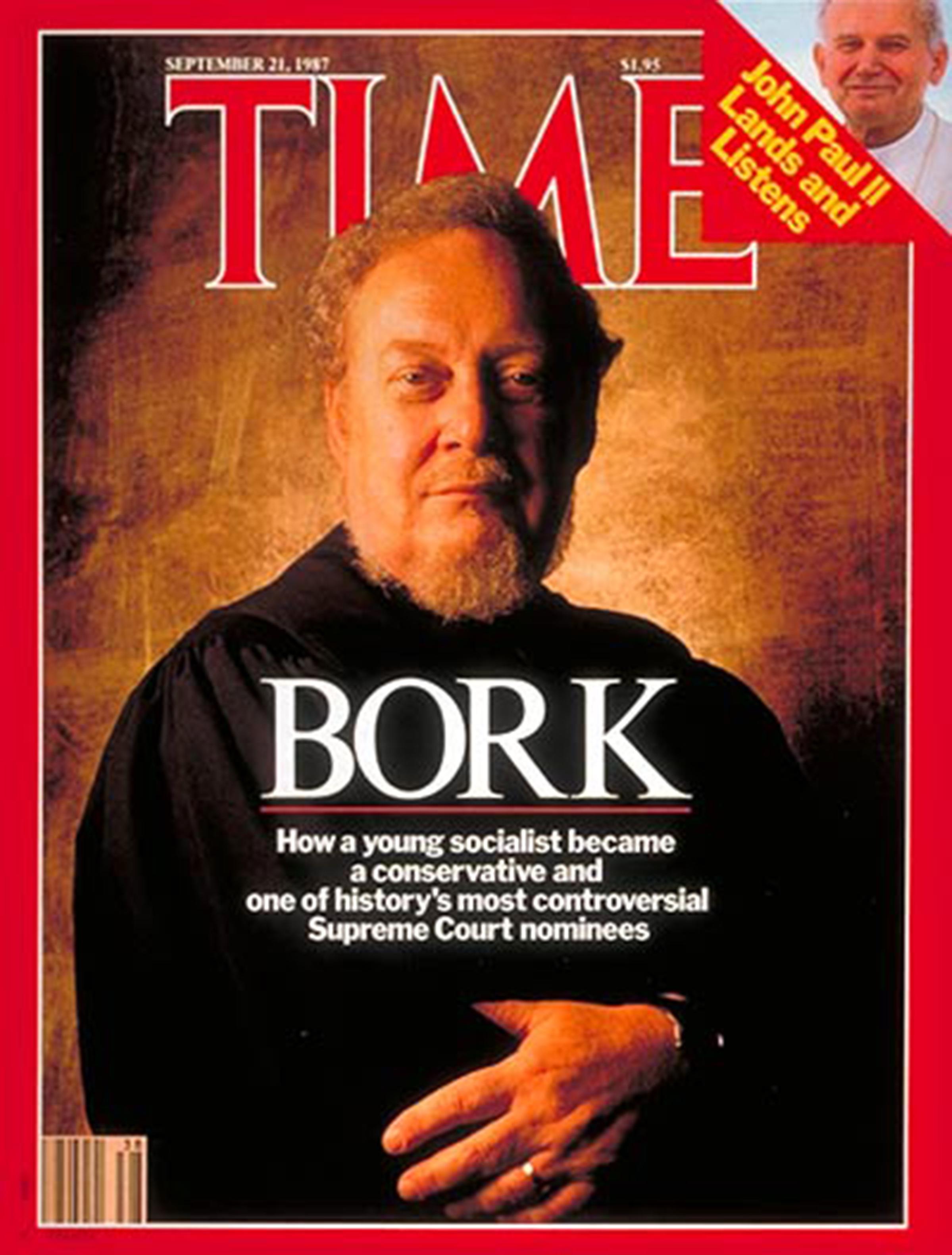

The partisan polarization of the confirmation process is often seen as reaching a new stage in 1987.

Then, as now, a swing seat was up for grabs. After Ronald Reagan nominated Robert Bork to the seat, Senator Edward “Ted” Kennedy (D-MA) “seized the narrative,” Perry says, and painted him as too conservative for the Senate, which had gone Democrat during the 1986 midterms. The gist of Kennedy’s argument was that Bork’s view of the world was out of step with the rest of Washington and the country.

“Robert Bork’s America is a land in which women would be forced into back-alley abortions, blacks would sit at segregated lunch counters, rogue police could break down citizens’ doors in midnight raids, schoolchildren could not be taught about evolution, writers and artists would be censored at the whim of government, and the doors of the federal courts would be shut on the fingers of millions of citizens for whom the judiciary is often the only protector of the individual rights that are the heart of our democracy,” Kennedy said in a speech on the Senate Floor.

That speech — bolstered by Bork’s long paper trail of conservative opinions and his role in the Saturday Night Massacre during the Watergate scandal — galvanized liberal interest groups. Then, as now, the future of Roe v. Wade was seen as at stake; it was revealed that Bork had characterized the case as “unconstitutional” and a “serious and wholly unjustifiable judicial usurpation of state legislative authority.” TIME reported back then that the Senate Democrats’ approach to Bork’s confirmation hearing shifted from “questions of their legal ability and ethical fitness” that characterized hearings of yore to “a frank confrontation over ideology.”

Bork became a political liability and by the time his nomination came to a vote, his rejection was seen as a foregone conclusion.

After Bork, nominees would aim to get through confirmation hearings without saying too much, answering Senators’ questions in a way that avoided ruffling feathers. “You don’t answer these questions directly. You hide behind language,” as David Yalof, author of Pursuit of Justices: Presidential Politics and the Selection of Supreme Court Nominees, summed up a legacy of the Bork controversy. For example, John Roberts likened judges to umpires who merely “call balls and strikes” during his 2005 confirmation hearings, asserting that he would not bring any personal agenda into play.

The Bork process also empowered conservative legal organizations to get involved in the process. “Trump takes it to a new level by asking interest groups whom they want on the Supreme Court as a presidential candidate,” says Perry. Kavanaugh hinted at such input in his remarks on Monday when he said, “No president has ever consulted more widely or talked with more people from more backgrounds to seek input about a Supreme Court nomination.”

After Bork’s failure, President Reagan nominated Douglas Ginsburg, a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia. But Ginsburg withdrew his nomination after it was revealed that he smoked marijuana as a law professor, which put him at odds with the administration’s war on drugs and “Just Say No” public health campaign. That’s when Reagan nominated Anthony Kennedy.

4. The Nominee Raises Ethical Concerns

In certain cases, the information that damaged the credibility of nominees had little to do with their judicial pasts.

In the run-up to the 1968 presidential election, President Lyndon B. Johnson nominated Associate Justice Abe Fortas to replace retiring Earl Warren as Chief Justice. During the hearings, it was revealed that Fortas had accepted a teaching gig at American University’s law school that came with a privately-funded stipend of $15,000 — equivalent to 40% of his salary on the bench — “donated by five big businessmen who some day may well have matters of interest come before the court,” as TIME reported back then. He was also scrutinized for accepting a $20,000 consulting gig with the family foundation of Louis Wolfson, who’d been indicted on securities fraud. He also faced the appearance of conflict of interest in terms of the separation of powers; TIME reported that he remained a close advisor to LBJ while on the bench.

Fortas is considered to be the first SCOTUS nominee to be blocked by a filibuster. After a vote to end debate came up short, LBJ withdrew the nomination at Fortas’ request. He stayed on the court as an Associate Justice, “in an attempt to vindicate himself,” as TIME put it, but his conflicts of interest created a cloud over him and he resigned in May of 1969.

5. It’s a Presidential Election Year

A new method of pushing against confirmation was introduced in 2016, when Merrick Garland, the Chief Judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, became Barack Obama’s nominee to replace the late Antonin Scalia, less than a year before a presidential election. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) did not schedule hearings for Garland, because, as he put it, “The American people should have a voice in the selection of their next Supreme Court justice. Therefore, this vacancy should not be filled until we have a new president.”

Until 2016, “No nominee had been denied a hearing since hearings began,” says Perry.

McConnell’s logic was new, according to Perry, who crunched the numbers and found that about one-third of U.S. presidents have nominated jurists to the Supreme Court and had those nominations accepted — 14 presidents putting forward 21 justices, to be exact. Of those, six presidents got nominees through as lame ducks. Not to mention, she points out, the Constitution doesn’t actually involve the people in the selection of justices; just the President to nominate people to the Supreme Court, “with the advice and consent of the Senate.”

What’s Next

So how can Supreme Court nominees get confirmed in such a polarized political climate?

For Kavanaugh, who faces friendly numbers in the Senate, it’s unlikely to be an issue, but historically even candidates facing a hostile Senate have been able to make it work. As Geoffrey R. Stone, law professor at the University of Chicago, wrote in 2016 for TIME.com, since 1955, “even when the Senate is in the hands of the opposition party, nominees have been easily confirmed if they are (1) perceived to be very highly qualified; (2) they are perceived to be moderate in their views; or (3) their confirmation is seen as unlikely to have a significant impact on the ideological balance on the court.”

There are reasons liberals could come to like Kavanaugh, but the vote is still likely to be close. For one thing, Kavanaugh was on the Republican legal team fighting the Florida recount in Bush v. Gore, which handed Bush the presidency over former Vice President Al Gore, and Democrats are still livid over the way Senate Republicans treated Merrick Garland.

“I’ve had a hard time getting over the way Merrick Garland was treated,” said Senator Tom Carper (D-DE), a New York Times reporter tweeted Monday. “That was shameful.” In other works: let the showdown begin.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com