The 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution may have been ratified 150 years ago — on July 9, 1868 — but Monday’s news is clear proof that the amendment is as timely as ever.

With President Donald Trump set to announce on Monday night his nominee to replace retiring Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy, one particular case in the court’s history is front-of-mind for advocates on both sides of the aisle: Roe v. Wade, the landmark 1973 decision ruling that prohibiting abortions was unconstitutional. Abortion-rights advocates worry that Kennedy’s replacement could increase the chance that Roe would be overturned, and those on the other side of the issue eagerly hope for the fulfillment of Trump’s campaign promise to nominate someone who would do exactly that.

And at the heart of the Roe decision is the 14th Amendment.

In its Due Process clause, the 14th Amendment states, “No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

As TIME explained shortly after the decision was handed down, Justice Harry A. Blackmun, writing the opinion for the majority, ruled that this clause included an implicit right to privacy for women deciding whether to terminate a pregnancy:

Blackmun held that such a right has now become an indivisible part of every American’s “liberty,” which is specifically protected by the due-process clause of the 14th Amendment. Such a protection, he indicated, more than overcomes any state interest in using abortion statutes — as so many states have — to regulate sexual conduct, however indirectly. A fetus, he added, is not a person under the Constitution and thus has no legal right to life — a conclusion that countless antiabortionists violently object to. Blackmun was also swayed by the fact that most abortion prohibitions were enacted in the 19th century when the procedure was more dangerous than now. His different standards for different stages of pregnancy are largely a reflection of medical progress. Abortion in the first three months, he pointed out, has become at least as safe as childbirth. After that, he said, because the dangers do increase, so should the states’ authority to protect the health of the mother.

Not everyone agreed that Blackmun’s reasoning made sense. In a dissenting opinion, for example, Justice William H. Rehnquist argued that “a transaction resulting in an operation such as this is not ‘private’ in the ordinary usage of that word.” And some jurists and scholars who are on board with the Roe holding still disagree about whether a right to privacy can really be found in the amendment, or about whether Blackmun properly explained his reasoning.

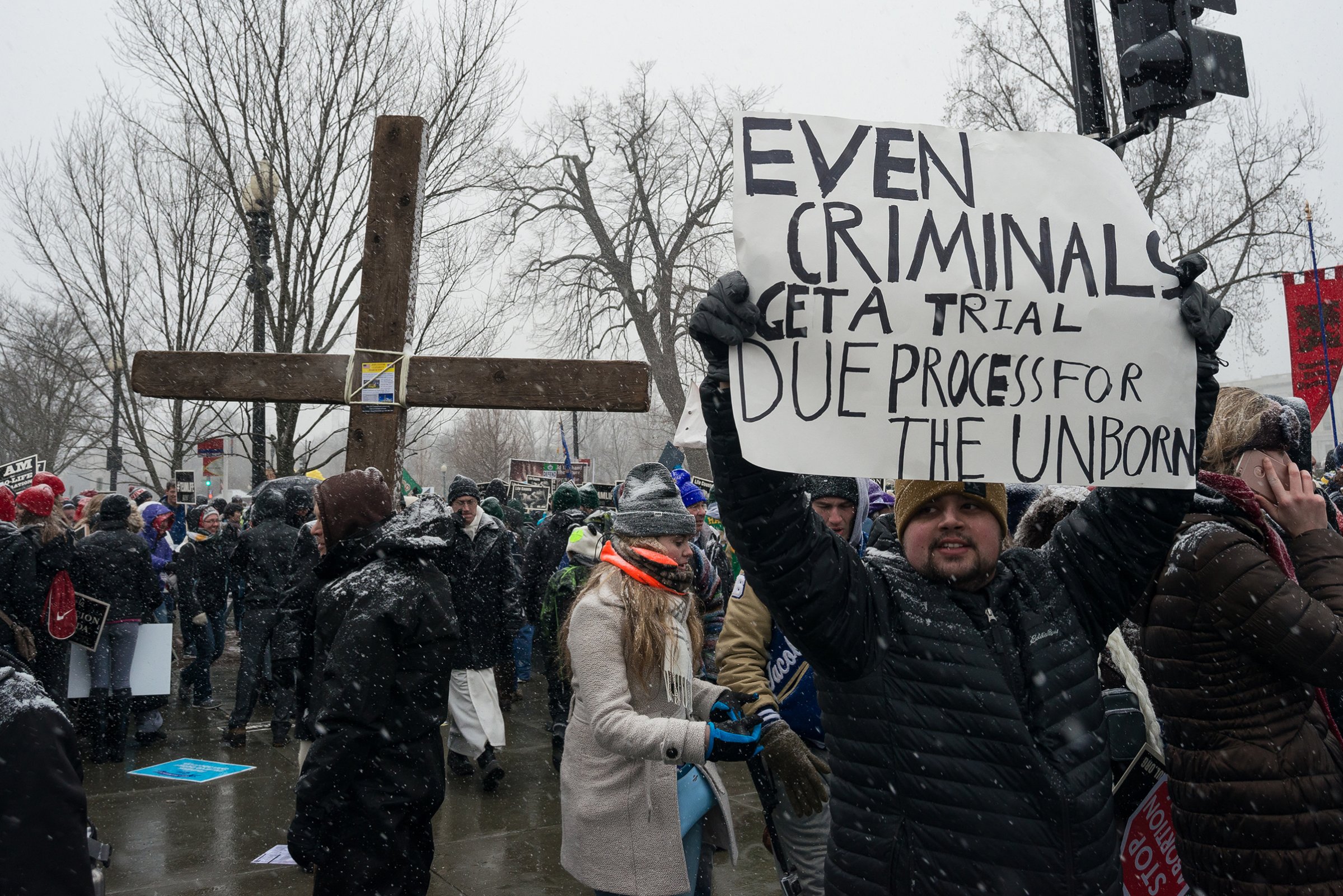

Even those who disagree with the Roe decision sometimes turn to the 14th Amendment for answers. Some have called for “Congress to legislate that unborn children are persons under the 14th Amendment,” as the National Review sums up that side of the issue; if that were the case, the fetus would also have a right to due process and other protections, though the first part of the amendment does specify that citizens are people “born or naturalized” in the U.S. That argument gained steam in the 1980s, as Roe v. Wade backlash became more of a conservative rallying point. In this period, as historian Daniel K. Williams recently wrote, antiabortion activists began lobbying presidents to pick like-minded jurists for federal courts and abortion-rights supporters responded in kind; Williams cites the 1987 rejection of President Reagan’s Supreme Court nominee Robert Bork, who had voiced his opposition to Roe, as a turning point in the conservative effort to lobby for a nominee who would overturn the case.

Roe is far from the only case that involves the relationship between the 14th amendment and privacy rights. But, because of the close ties between the case and the amendment, if the Supreme Court does decide to revisit Roe v. Wade in the future, it could have a ripple effect on the interpretation of the amendment.

Like many laws and parts of the Constitution, the meaning of the 14th Amendment is still being debated 150 years later. But that’s not necessarily a bad thing, argues historian Eric Foner, who wrote on the occasion of the amendment’s anniversary that Americans should “embrace” its “imprecise” language: “Ambiguity,” he wrote, “creates possibilities.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com