Though U.S. President Donald Trump’s visit to the U.K. this week has sparked protests, with hundreds of thousands planning to demonstrate in London on Friday, the relationship between those nations and their leaders is typically a close and friendly one. In fact, it’s so friendly — and, experts say, so unusual in its specifics — that it has its own name: the “special relationship.”

But why do we call it that? Why not just call it an alliance?

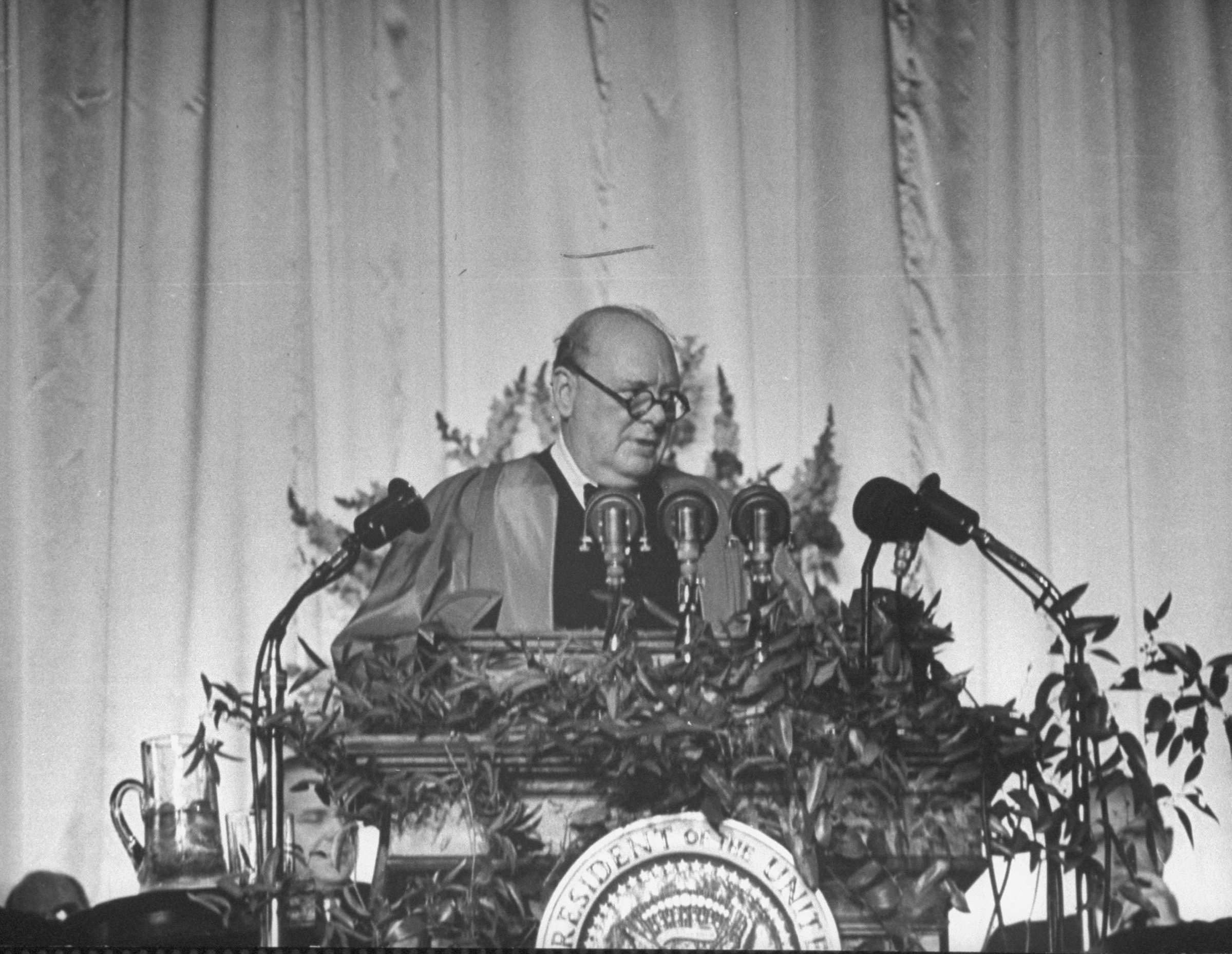

The phrase can be traced back to Mar. 5, 1946, when Winston Churchill addressed Westminster College in Fulton, Miss., where he and President Harry S. Truman received honorary degrees. (This is the same speech in which he famously used the metaphor of the “Iron Curtain” dividing capitalism in Western Europe and Communism in Eastern Europe — though he didn’t invent the term.)

Here’s what he said about the “special relationship”:

I come to the crux of what I have travelled here to Say. Neither the sure prevention of war, nor the continuous rise of world organisation will be gained without what I have called the fraternal association of the English-speaking peoples. This means a special relationship between the British Commonwealth and Empire and the United States… Would a special relationship between the United States and the British Commonwealth be inconsistent with our over-riding loyalties to the World Organisation? I reply that, on the contrary, it is probably the only means by which that organisation will achieve its full stature and strength.

Churchill emphasized the need for the two powers to band together against the Soviet Union, rebuilding the ravaged Europe so that it didn’t become one big Soviet satellite.

“The real purpose of the speech, more than anything else in my opinion, was to try to talk about the appalling economic problems that western Europe was suffering in ’46 [between the] terrible winter in Germany, people dying of starvation, Berlin devastated, flattened by bombing,” says historian Warren Kimball, author of Forged in War: Roosevelt, Churchill and the Second World War. “He’s there to ask the U.S. for economic help but never asks the question in a straightforward way, so he refers to the special relationship that U.S. and Britain had. We demonstrated how well we could work together during the war, so we could work together for the peace, and the peace can include economics.”

Indeed, President Truman would sign into law the Marshall Plan, providing U.S. aid to rebuild Europe, about two years later on April 3, 1948.

Though it wasn’t the beginning of that relationship — after all, Churchill was pointing to something that already existed — that moment started a new way of looking at the relationship between the two countries. It’s come to represent a certain closeness and more than seven decades of sharing intelligence and nuclear relations.

But obviously the history between the two countries is even deeper than that, and it arguably makes the alliance unlike any other in the world.

“There was no special relationship before [World War II]. There was friendly relationship,” according to historian Kathleen Burk, author of Old World, New World: Great Britain and America from the Beginning. Before the term ‘special relationship’ was coined, “the U.S. and British fought each other as often as they were allies.” Here’s a look at key moments in the evolution of the special relationship throughout history:

In the Beginning…

Of course, the United States of America has always had a unique relationship with Britain, even if it wasn’t called a “special relationship.” The early colonial connection between the two meant a shared language and certain shared cultural elements, but it was also the source of great tension.

Obvious examples of the fighting Burk mentions are the American Revolution — the war against Britain that first established the U.S. as its own country — and the War of 1812. During the Civil War, the British supported the Confederacy rather than the Union, because the South was its connection to cotton.

“During most of the 19th century, a lot of the European powers waited for the U.S. to break apart, and it seemed like that would happen until Gettysburg,” says Burk. “The fact that the U.S. remained a unified power after the Civil War made it clear, [America] was a unified country and [it] wasn’t going to fall apart and [it was] a country you have to pay attention to.”

It’s after the Civil War, she says, that the two nations stopped working against one another, even if they weren’t yet working together. The special relationship was then able to develop “little by little, step by step,” as she puts it, from that period through World War II.

The British supported the Americans during the Spanish-American War in 1898, and the U.S. government — unlike most European nations — supported the British in the second Boer War (1899-1902). The U.S. waded into World War I in the early 20th century, but became more closed off after. “American leaders were disappointed in how [the war] turned out and didn’t see themselves as involved in Europe, so they turned back inside,” as Burk puts it.

The “Special Relationship” During World War II

The “special relationship” that Churchill spoke about continuing is the one that blossomed in a specific context: his alliance with President Franklin Delano Roosevelt during World War II.

They didn’t have much of a choice but to work together; as Jon Meacham wrote in TIME, “it was a matter…of life and death.” But they also found out they had the same interests. As he wrote in Franklin and Winston: An Intimate Portrait of an Epic Friendship, “They loved tobacco, strong drink, history, the sea, battleships, hymns, pageantry, patriotic poetry, high office, and hearing themselves talk.”

The Atlantic Charter, a joint declaration from the two, spelled out guiding principles for defeating Hitler in August of 1941. After Pearl Harbor, they became even closer, as Churchill literally moved into the White House and stayed through Christmas so that he and Roosevelt could plot strategy in person. “Never before had a wartime Prime Minister of Great Britain visited the U.S.,” TIME reported in Jan. 5, 1942. “This meeting might possibly be the first broad hint that some day the two nations might draw together.” Later that year, FDR did not to hesitate to offer reinforcements when the British troops in Tobruk, Libya, were forced to surrender to German and Italian troops in June 1942. “Churchill is talking to Roosevelt in the White House when they learn the news, and [Roosevelt] basically told Marshall to do what Churchill wanted,” says Kimball.

Their friendship is enshrined in Westminster Abbey. Unveiled on Nov. 12, 1948, a stone tablet dedicated to FDR reads: “To the honoured memory of Franklin Delano Roosevelt 1882 – 1945 a faithful friend of freedom and of Britain. Four times President of the United States. Erected by the Government of the United Kingdom.” It was the first memorial to a foreign head of state in “Britain’s most hallowed shrine,” as TIME reported. In a brief speech, Churchill, “in a voice he could hardly control,” said the tablet “proclaims a growth of enduring friendship and a rebirth of brotherhood between two great nations upon whose wisdom, valor and fortitude the future of humanity in no small degree depends.”

The “Special Relationship” After World War II

What Churchill and FDR began, their successors have largely continued.

American diplomats have long echoed the importance of maintaining the “special relationship” with Britain. “No other country has the same qualifications for being our principal ally and partner as the U.K.,” declared a U.S. State Department policy paper written in 1950, right before the Korean War. “The British and with them the rest of the Commonwealth, particularly the older dominions, are our most reliable and useful allies, with whom a special relationship should exist… We cannot afford to permit a deterioration in our relationship with the British.”

As Walter Annenberg, Nixon’s Ambassador to the U.K., once put it more bluntly, “I have always maintained that England and America belong in bed together.”

Of course, as with any alliance, the “special relationship” has had its ups and downs. Militarily speaking, it doesn’t mean that Britain will always jump when America calls, and vice-versa. The Suez Canal crisis tested the relationship between President Eisenhower and Prime Minister Harold Macmillan after Britain and France invaded Egypt in 1956, after Cairo nationalized the Suez Canal. “The British soon withdrew, confronted by the Eisenhower Administration’s objections to the operation and a rising tide of criticism at home,” TIME later reported. “In so doing, they also had to face a fact that they had resisted until then: the sun had set on the British Empire.” John F. Kennedy is crediting with salvaging the “special relationship,” actually becoming friends with Macmillan.

Later, when President Lyndon B. Johnson asked U.K. Prime Minister Harold Wilson to send combat troops to Vietnam in the mid-’60s, Wilson refused. When Britain’s economy hit hard times after “it liquidated its imperial holdings,” TIME’s Feb. 2, 1970, issue reported that the “special relationship” had “grown steadily less special” as well “unbalanced” and “unproductive.”

President Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher are credited with “reinvigorating the special relationship,” forging arguably the strongest special relationship since the bond between FDR and Churchill. She became “Reagan’s closest ally in placing new nuclear missiles in Europe to counter Soviet deployments in the early 1980s,” as TIME put it in 1990. Robin Renwick, former senior diplomat in the British Embassy during the Falklands crisis, said that if the U.S. Secretary of Defense hadn’t agreed to provide Sidewinder missiles to Britain, “we wouldn’t have been able to re-take the Falkland Islands.” Renwick has recalled that Joe Biden assured him and the British Ambassador to the U.S. Nicholas Henderson, “Forget all this crap about self-determination, we’re going to support you because you are British!”

Prime Minister Tony Blair and George W. Bush also seemed particularly close when both troops invaded Iraq, though a 2016 review of documents suggests Blair was fighting back more behind the scenes than people thought. (The best known pop-culture take on the idea of a British PM being pushed around by a bossy American President is the scene in the 2003 film Love Actually in which Hugh Grant, whose character appears to be modeled after Blair, gives a rousing speech resisting an attempt by a Clinton-Bush hybrid president to steamroll him.)

And the special relationship is more consistent than we realize; a common language facilitates common pop-cultural references, and when the special relationship is talked about, it’s usually in a positive way. A February 2017 Times of London poll expressed that nine out of ten Americans believed that the transatlantic tie was “very important” or “somewhat important.” Perhaps if the above examples throughout history prove anything, it’s that leaders will come and go, but the two nations’ ties and a shared history have withstood the test of time.

As both Kimball and Burk both coincidentally described it to TIME, it’s not just a relationship, but an inclination.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com