It was the summer after his sophomore year in college when Luke finally found the nerve to have sex with another man. He’d grappled with his sexuality since his adolescence in Southern California: He knew he was attracted to men, but he was also the son of two church leaders he felt would surely disown him.

“My whole life revolved around the church and making my parents proud,” he tells TIME. (He requested that his last name not be printed.) “I was even leading a campus church group while battling with my sexuality. I couldn’t tell anyone. Eventually, I decided I wanted to try out actually being with another guy and didn’t know how to find others without joining a gay dating app.”

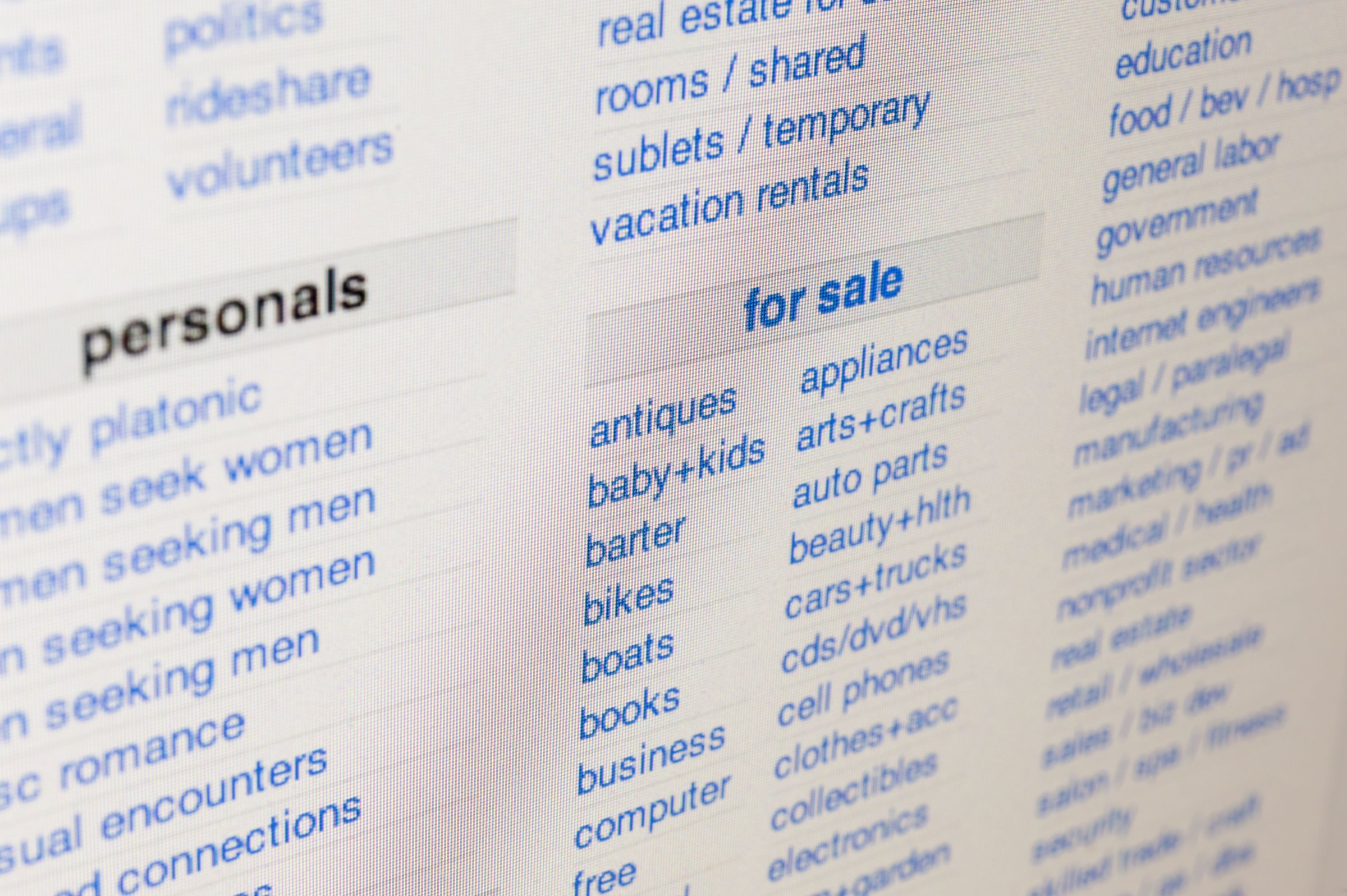

So he went to Craigslist, where he posted a free, anonymous ad that caught the eye of another guy online. For four more years, Luke used the classified ads site to meet men before coming out and leaving the church in his twenties. But this past weekend, when he went to post an ad on Craigslist’s personals page, he was redirected to a statement informing him it no longer existed.

“Any tool or service can be misused. We can’t take such risk without jeopardizing all our other services, so we are regretfully taking Craigslist Personals offline. Hopefully we can bring them back some day,” the statement reads. “To the millions of spouses, partners, and couples who met through Craigslist, we wish you every happiness!”

The decision by Craigslist to stop hosting personal ads came as a preemptive move after Congress passed the Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act, a sweeping piece of legislation intended to minimize human trafficking and unlawful prostitution in the internet era. The Senate cleared the bill overwhelmingly, 97-2, last Wednesday and it awaits President Donald Trump’s signature. But critics — who range from free-speech activists to Silicon Valley executives — say it goes too far.

The legislation targets websites that “promote or facilitate” prostitution, even in jurisdictions where prostitution is legal; individuals operating those sites face up to ten years in prison. And the broader risk of being found to have facilitated prostitution led Craigslist and Reddit, which runs online messaging boards, to shutter sections of their sites.

There is little debate, even among its opponents, about the legitimacy of the bill’s ambitions. Nearly 5,600 cases of sex trafficking in the U.S. were reported to the National Human Trafficking Hotline in 2016 — more than 2,000 of which concerned minors. But critics argue that the bill’s broad reach in fact serves to endanger the far greater demographic of women in the U.S. — at least one million, by some estimates — who are sex workers of their own volition. According to one recent study conducted by economists at Baylor University, escort ads on Craigslist reduced the female homicide rate by 17.4% from 2002 to 2010. Allowing sex workers to advertise their services online kept them off the streets, and also gave them the opportunity to better screen potential clientele.

And for other marginalized communities — such as people who are LGBT or simply have unorthodox proclivities that they would be embarrassed to have publicly known — sites like Craigslist also provided an outlet, whether they were searching for platonic endeavors, one-night stands or long-term romantic relationships.

“It was the only way I could live my true life without having to destroy my Christian image among family and the church,” says Luke.

The bill’s ambiguous terms threaten to impugn not only Craigslist, but any website or forum that accommodates discussion of the sex trade. Many sex workers say these sites are crucial to their safety: they provide the community with a platform to share information about dangerous clientele (known as “bad date lists”) and other occupational hazards. Advocates for these communities have also argued that eliminating the sex trade’s online presence will in fact make cases of actual human trafficking harder to identify.

“It’s already sending a number of people back to street-based work,” Kate D’Adamo, a longtime advocate for sex workers, tells TIME. “And these websites are the first places people went when they want to leave street-based work, because with street-based work, you’re talking about four to six times more violence.”

“It’s put a lot of fear in [sex workers] — not just about being kicked off platforms, but the fact that they created a new federal crime,” she continues. “I’m getting calls from organizers saying ‘how do I host a website or a listserv if it means facing 25 years in prison?’”

“The most disturbing aspect of the legislation is its very broad definition of ‘the promotion of prostitution,’ which could definitely be read to sweep in some of the harm-reduction tactics that sex workers rely on,” Ian S. Thompson, a legislative representative with the American Civil Liberties Union, tells TIME. “This was a sloppy effort at addressing a very serious problem. It’s going to harm some of the very individuals that well-meaning members of Congress were actually trying to protect.”

The bill has been widely panned by civil rights groups since it was introduced last April. Many civil liberties advocates say its measures are not merely counterproductive: they deliver an unprecedented blow to the freedom of speech in the digital era. Since the mid-1990s, Section 230 of a law known as the Communications Decency Act has protected websites from being held responsible for what their users post. It was this law that shielded Backpage.com, a similar classifieds site, after ads featuring underage girls were found on its forums. (Backpage hosted about 25% of sex work ads online; Craigslist, the second-most popular, had about 14%, according to a 2014 study.)

No longer. A coalition of major Silicon Valley shops, most notably Google and Facebook, were quick to speak out in opposition to the new bill, arguing that it “jeopardizes bedrock principles of a free and open internet, with serious economic and speech implications well beyond its intended scope.” (The firms later backed down after tweaks to the bill’s language — a move that many industry watchers described as a necessary concession at a moment when Silicon Valley is in Congress’ crosshairs.)

“It’s likely that many of today’s online platforms would have never formed or received the investment they needed to grow and scale — the risk of litigation would have simply been too high,” Elliot Harmon, an activist with the digital civil rights organization Electronic Frontiers Foundation wrote in a post on March 21. “It’s easy to see the impact that this ramp-up in liability will have on online speech: facing the risk of ruinous litigation, online platforms will have little choice but to become much more restrictive in what sorts of discussion—and what sorts of users—they allow, censoring innocent people in the process.”

The bill passed the Senate last Wednesday overwhelmingly, with only two members — Sen. Ron Wyden of Oregon and staunch libertarian Sen. Rand Paul of Kentucky — voting against it. Just three weeks prior, the Department of Justice had written to Congress expressing misgivings about the legislation’s ability to simplify the prosecution of sex crimes, and noting that the bill’s retroactive powers were outright unconstitutional.

“Taking down ads doesn’t mean the pimps and predators start following the rules. When the ads come down, the criminals scurry to the darker corners of society,” Wyden, who coauthored Section 230 while serving in the House, said on the Senate floor last week. “Today we take a real step backward, and down a path we will regret.”

Critics say the bill’s pitfalls could have been avoided had its authors better engaged with the population affected by it. “Sex workers were nowhere to be found, and we were the ones who predicted exactly what would happen,” D’Adamo says. “There is an expertise that is missing from these conversations.”

“The sex worker community had been urging Congress to hit the time out button and work with the individuals who are going to be impacted,” Thompson at the ACLU says. “It’s a bill that we urged both the House and the Senate to oppose, both from the practical impact on sex workers as well as the chilling aspect on the ability to use the internet as a place for free expression.”

Impacted communities are starting to take up arms against the new bill. “I have seen the community coming together in a way that I’ve never in ten years of organizing seen,” D’Adamo says. “This is a catalyst.”

In the meantime, the communities that have relied on these websites worry about the future. John Kopanas, the founder of FetLife, a kink-oriented social networking site with more than eight million users, wrote in a thread there on Monday night that “we are still gathering information so that we can make the best possible decision for FetLife.”

“But we probably don’t have too much time to figure out how [the bill] might impact us since the only thing left is for the bill to be signed.”

And on Craigslist itself, users are turning to the site’s other forums to hold makeshift vigils of sorts. Luke, the former evangelical who came to terms with his sexual orientation through encounters facilitated via Craigslist, says what he felt when he learned about the section’s end was akin to grief. “It was actually a huge moment for me,” he says. “It sounds stupid, but Craigslist gave me the opportunity to stay anonymous while trying to explore my sexuality.”

“I met my current girlfriend on casual encounters in 2015,” one Twitter user who gave his name as Barney tells TIME. “It’s been almost three years this June and it’s the best relationship of my life — and I’ve tried OK Cupid and plenty of other [dating sites.]”

“I have met friends, a lover or two, and at worst, an alright date on CL,” reads one advertisement posted to Craigslist’s San Francisco page. “I am disgusted. There are better ways to fight exploitation than causing a free market to shut down.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com