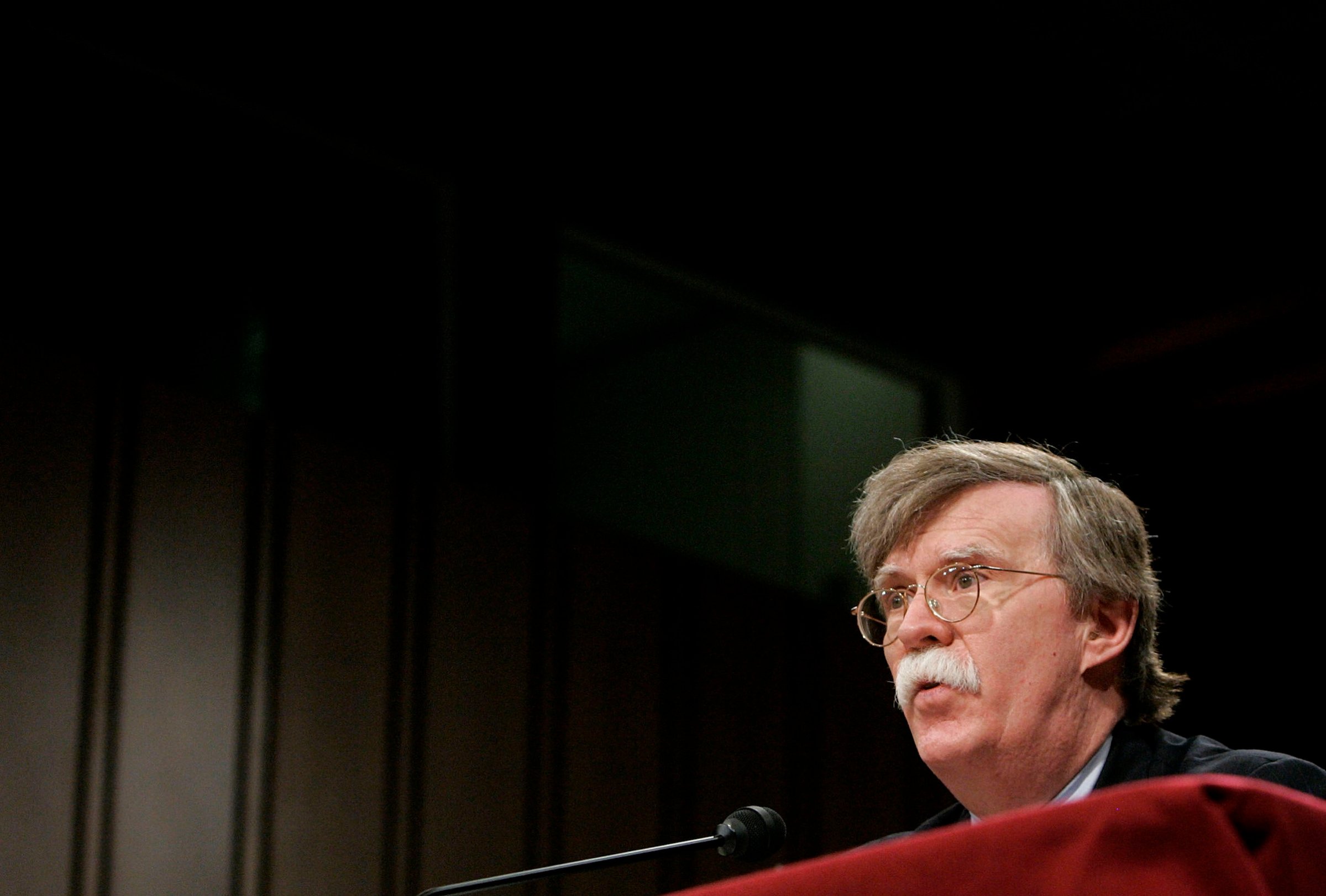

Though he won’t start in his new job for several weeks, John Bolton — who will replace Gen. H.R. McMaster in the role of National Security Advisor, President Donald Trump announced on Thursday — isn’t exactly an unknown quantity when it comes to his views on diplomacy and security. The ambassador, also a regular Fox News presence, has been a polarizing public figure in American international relations for more than a decade, and behind the scenes for even longer.

Notably, Bolton worked as under secretary of state for arms control and international security under President George W. Bush, and was picked to be the nation’s ambassador to the U.N. in 2005. And, during that era, he made clear his views about more than one subject that remains central to U.S. security.

For example, during a 2003 speech, Bolton famously took a hard line on North Korea, calling life there a “hellish nightmare,” right on the eve of talks with the country’s leaders. And, though he seemed somewhat optimistic about diplomatic solutions to the problem of Iran’s nuclear weapons in a 2006 interview with TIME, in 2007 he said that “Iran is not going to be chatted out of its nuclear-weapons ambitions” and the time had passed for trying to work out a deal.

As TIME reported while the Senate debated whether to confirm Bolton to the U.N. role, those hard-line views weren’t the only reason why his appointment was so controversial. Nor was the fact that he had once said that if the U.N. headquarters “lost ten stories, it wouldn’t make a bit of difference.” Rather, it was a question of character that led Senators to block votes on his confirmation for months, such that he ultimately got the job via a recess appointment by Bush.

Bolton had offended a host of Washington characters in his decades in government. Colin Powell had confessed to Senators that he was worried about the way Bolton mistreated subordinates, TIME reported, and 60 retired diplomats had sent a letter to the committee speaking out against the nomination. One former ambassador sent a note to Joe Biden, who was then the top Democrat on the committee considering the nomination, saying that Bolton “dealt with visitors to his office as if they were servants with whom he could be dismissive, curt and negative.”

But the problem wasn’t just that people were mad at him, the article explained:

[Opponents] say the problem is more than a matter of bad manners and bruised egos: Bolton’s pattern of intimidation, they claim, was also aimed at distorting vital intelligence. Government sources tell TIME that during President Bush’s first term, Bolton frequently tried to push the CIA to produce information to conform to—and confirm—his views. “Whenever his staff sent testimony, speeches over for clearance, often it was full of stuff which was not based on anything we could find,” says a retired official familiar with the intelligence-clearance process. “So the notes that would go back to him were fairly extensive, saying the intelligence just didn’t back up that line.”

Those episodes, sources say, frequently involved statements Bolton wanted to make about the malign intentions and weapons capabilities of Cuba and North Korea. Two analysts—one at the State Department and the other at the CIA—told the committee they had run afoul of Bolton in 2002 after they warned that he was making assertions in a speech about Cuba’s weapons programs that could not be backed up by U.S. intelligence. Bolton, they said, tried to have them removed from their jobs. Witnesses say that after one of the analysts, Christian Westermann, wrote an internal memo warning of Bolton’s embellishments, he was summoned to Bolton’s office and subjected to a finger-wagging tirade. Westermann’s boss at the time, Carl W. Ford Jr., told the committee in a public hearing two weeks ago that he considered Bolton “a serial abuser” of underlings and “a quintessential kiss-up, kickdown sort of guy.”

Fulton Armstrong, then head of the Latin American division at the CIA’s National Intelligence Council, told the committee in private that he was subjected to similar mistreatment by Bolton after he raised objections to the contents of the Cuba speech. Bolton denies pushing to get anyone fired, and his supporters point out that neither Westermann nor Armstrong lost his job. Bolton testified that he did ask to have Armstrong reassigned because he had “lost confidence” in him, although he never worked with him or even met him.

…The biggest danger facing Bolton is suspicion that he deliberately misled Senators in his public testimony defending himself against these challenges. Already they have statements from Thomas Hubbard, who was President Bush’s ambassador to South Korea during his first term, saying Bolton misrepresented Hubbard’s views about the bitingly anti-North Korea speech Bolton gave in July 2003, just days before the launch of delicate six-nation talks aimed at persuading Pyongyang to give up its nuclear-weapons program. The speech—in which Bolton vilified Kim Jong Il as a “tyrannical dictator” and said life in North Korea was a “hellish nightmare”—infuriated the North Korean government and, U.S. diplomats say, nearly torpedoed the talks. In defending his undiplomatic language, Bolton told Senators that it had been cleared by relevant officials and that Hubbard had personally thanked him for it.

Hubbard contacted the committee last week and said he had, in fact, opposed the speech and had thanked Bolton only for making some specific minor changes to it that Hubbard had requested. According to a memo obtained by TIME describing Hubbard’s interview last Friday with committee Republicans, the former ambassador “says he strongly disagreed with the tone of the speech, especially at the sensitive time in the negotiating process, and asked Mr. Bolton to tone it down. He did not.” Retired Ambassador Charles Pritchard, who was then special envoy for negotiations with North Korea, tells TIME he never approved Bolton’s speech either. “I had a chance to see [a draft of] the speech in advance and refused to clear it,” says Pritchard.

As one State Department official put it, “John was always a strong friend of his own opinion.”

The nature of Bolton’s recess appointment meant that his tenure at the U.N. was relatively short, but his time in the public eye didn’t end when that job did. He is to officially take over the job of National Security Advisor on April 9.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com