Shortly before the release of Darkest Hour, Joe Wright’s acclaimed film about Winston Churchill, a private screening was held for members of Churchill’s family. Among those who attended was Nicholas Soames, Churchill’s grandson, who knew his grandfather when he was an old man.

He reserved particular praise for the commanding performance of actor Gary Oldman, who plays Britain’s wartime prime minister and is a favorite to win an Oscar for Best Actor on Sunday night.

“There have been brilliant Churchill actors before,” Soames told the Express after the screening, “like Robert Hardy, and there have been some absolute snorkers — but I think Gary Oldman has absolutely nailed it. They each have their own way of doing it, but his portrayal of my grandfather is very vivid. One of the very best.”

Darkest Hour is a heady cocktail of history and drama, casting the real-life Churchill in the mold of a Shakespearean protagonist — a whisky-fuelled belligerent whose strengths are equally matched by flaws. At times arrogant, at times petulant, he is also witty and occasional even endearing.

But was he like this in real life?

The answer reveals a great deal about both Churchill’s character and outlook. Britain’s wartime prime minister was a complex mesh of a man — a result, perhaps, of his unorthodox upbringing. Grandson of a duke, born in Blenheim Palace and educated at the elite Harrow School, he was an archetypal late-Victorian aristocrat. Yet he was an aristocrat with a twist. His mother, Lady Randolph (née Jenny Jerome), was an American-born socialite — an eccentric, thrice-married political activist who wrote plays for London’s West End theatres. Thanks to her parenting, Churchill knew how to play to many different audiences.

The same could be said of Darkest Hour, which owes much of it strength to a fine script by the Academy-Award nominated writer Anthony McCarten. The narrative roars us through the first week of May 1940, with Churchill bullying his ministers into rejecting any negotiation with Hitler.

McCarten’s self-professed devotion to research and historical fact is admirable. Much of the film could indeed have come straight from the archives. Churchill certainly did bully and cajole his fellow parliamentarians into adopting his fighting spirit, and Lord Halifax, the Foreign Secretary, did indeed want to keep open the channels of negotiation with Hitler.

And we can perhaps forgive the movie for eschewing historical accuracy in favor of dramatic tension on certain occasions, such as when Churchill’s predecessor as Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, is wrongly portrayed as an appeasing pacifist whose views are unchanged since he concluded his infamous Munich Agreement with Hitler. But when a more grievous historical fault occurs in one of the most striking moments in the film, when Churchill leaps from his chauffeur-driven car and descends into the London Underground, it’s worth paying attention. Churchill does so, suggests McCarten, because he is keen to hear the wartime opinions — and seek the advice — of ordinary Londoners. The problem is not that this exact moment is fictionalized, as such set pieces are to be expected in a film, but rather the incorrect conclusions it might lead one to draw about the real man at the center of the movie.

It’s a memorable piece of drama, with Churchill chatting convivially to everyday folk on the underground train before launching into a stirring recital of the Lays of Ancient Rome by Victorian essayist Thomas Macaulay. This, in itself, is highly implausible, but McCarten nudges it further into the realms of fiction by having a young black Londoner step forward and finish Churchill’s recitation with flawless perfection.

It is most unlikely that any of the working class people on that underground train would have had access to the same privileged education as Churchill, and therefore be in a position to quote Macauley by rote, but that is not why Nicholas Soames picked this moment as the only scene in the film that struck a duff note. “The idea of my grandfather on the Underground is absolutely preposterous,” he said. “He’d never been on a bus in his life.” He much preferred the comforts of a 1936 Rolls Royce Phantom III, driven by a starch-collared Whitehall chauffeur.

Equally preposterous is the idea of Churchill canvassing Londoners on their views about British foreign policy toward Hitler. McCarten insists that “this is the kind of thing he did right through the war.”

Such meetings were not recorded in his meticulous desk diary, and I’d wager a box of Romeo y Julieta that he never did such a thing — ever. Churchill certainly kept his finger on the political pulse, as does every successful politician, but he did not consult with the traveling public about their views on Hitler, and certainly not in the spring of 1940. By the time he was installed as Prime Minister on May 10 of that year, he saw himself as the self-assured maestro of an orchestra that was there to do his bidding.

We know this because he said as much in an oft-quoted passage from his memoirs: “At last I had the opportunity to give directions to the whole scene. I felt as if I was walking with destiny and that all my past life had been but a preparation for this hour and for this trial.”

It is an inconvenient truth that Britain’s greatest prime minister had neither the need, nor desire, to formulate policy based on the views of working class commuters traveling on the London subway. However, much we might like to view Winston Churchill as a man of the people, he was no such thing. This uncomfortable fact is a reminder that life is often more complex than Hollywood would have us believe.

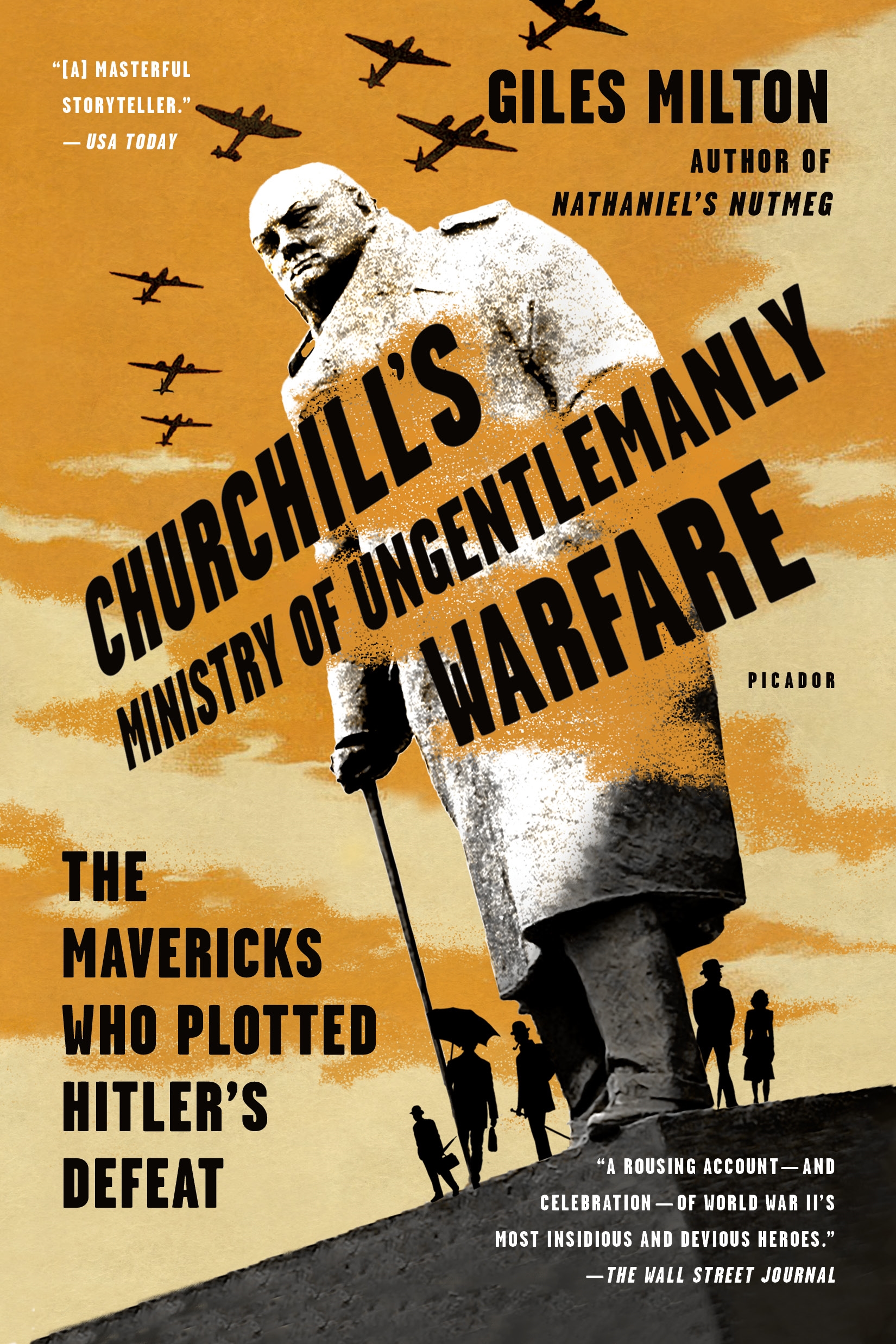

Giles Milton is the host of the Unknown History podcast. His books include the bestselling Nathaniel’s Nutmeg and, most recently, Churchill’s Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare. He lives in London.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com