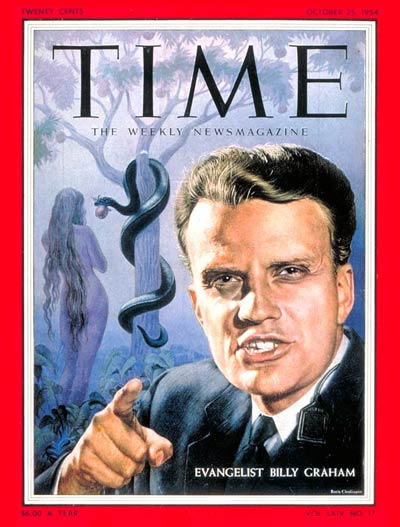

When he appeared on the cover of TIME in 1954, Billy Graham — the evangelist who died Wednesday at 99 — was already “the best-known, most talked-about Christian leader in the world today, barring the Pope.”

At that point, he had already traveled the nation and the world to preach to thousands. He also made a handful of movie appearances, wrote regular newspaper columns and was broadcast on radio programs, and it had only been a few years since he first made headlines by converting a couple of celebrities.

But it was more than just Billy Graham’s charisma and belief that drew crowds of converts. His “crusades” were complicated and well-planned events designed for maximum impact.

Here’s how they worked, as TIME explained it back then:

Before Graham agrees to conduct a campaign in any given city, preliminary negotiations may go on for years (New Orleans churchmen first began talking about the current crusade in 1950). Graham must be sure that he has the backing of the top Protestant churches in the area, as well as the support of business and civic leaders. After he accepts an invitation, the local sponsoring committee is promptly presented with a “Graham Plan” for financing.

Two months before the campaign is scheduled to begin, the first member of the Graham team arrives in town. Willis Haymaker, 57, who worked as advance man for such old-school soul-savers as Gypsy Smith and Bob Jones but thinks Billy is the greatest of them all, mobilizes the preachers and laymen of the cooperating churches into a vast cadre of workers. From 1,000 to 3,000 are tapped for choir duty. Between 700 and 1,000 become “counselors,” and about 1,500 become ushers. Women are selected to staff the ticket office and switchboards. Deacons, Sunday school superintendents and other church workers are organized into “followup” classes, where they are taught how to bring new converts into local church life. Says Graham: “We have a fair audience ready before we even get there.”

The town begins to sprout posters, street banners, window cards and bumper stickers announcing the impending crusade. Typical of the Graham team’s meticulous know-how is the way its members tackled the matter of bumper stickers. First they tested the different methods of attaching a sign to a bumper—string, elastic, clips, hooks, adhesive. Having decided adhesive was most lasting, they began testing surfaces, determined on a kind called “Dayglo” which shines in sunlight or headlight. Dayglo comes in single, double and triple screen, hence more testing and the decision to use double. To find the best adhesive, lots of 25,000 were tested in various cities.

While such promotion is being readied, counselors are trained in regular classes and graded on-a point system. About a dozen usually flunk and are tactfully asked to resign; marginal cases (especially those who dress sloppily) are held on “reserve,” and the best students become “front-row” counselors (wearing red tabs in their badges).

By the time Graham got to town, everything was ready to go. The “counselors” were ready to speak to anyone who stood up while Graham preached, to bring him or her to the “Inquiry Tent” to give them a pep talk and get the information needed to pass the new convert on to a local church. That practice of decentralized recruitment made Graham friends among clergy wherever he went, and helped those “baby Christians” stick with their newfound dedication.

And, though the well-rehearsed mechanism of a Graham crusade could have seemed impersonal or unseemly, Graham made sure it didn’t — mostly by believing so strongly in its urgency.

“I am selling,” he told TIME in 1954, “the greatest product in the world; why shouldn’t it be promoted as well as soap?”

Read the 1954 cover story, here in the TIME Vault: A New Kind of Evangelist

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com