Decades before Anita Hill, Gretchen Carlson or #MeToo, American companies dreamed up “diversity training,” typically a course that lasts anywhere from an hour to a couple of days, with the goal of wiping out biases against women and others from underrepresented groups. For most of its history, diversity training has been pretty much a cudgel, pounding white men into submission with a mix of finger-wagging and guilt-mongering.

The first training programs surfaced in the 1950s, after men returned from World War II and were appalled and perplexed to find women in their offices. After the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the training took on more urgency. Within a decade, it had morphed into a knee-jerk response to legal actions, after a series of high-profile sex-discrimination suits, including one by the women of Newsweek magazine, who were stranded in a pink ghetto. “Women don’t write at Newsweek. If you want to be a writer, go someplace else,” the bosses told them, according to Lynn Povich, one of the 46 women who sued.

By the time I entered the workforce in the 1980s, the Newsweek suit and others like it–led by women at TIME, the Associated Press and the New York Times–were mostly forgotten. Diversity training had taken a backseat too. I don’t recall ever hearing the phrase until the 1990s. By then, it had been reconstituted as a feel-good exercise in consciousness-raising. White men were told they should include women and minorities because it’s the right thing to do. It was all about the importance of “inclusion.”

But here’s the thing about diversity training: it doesn’t work.

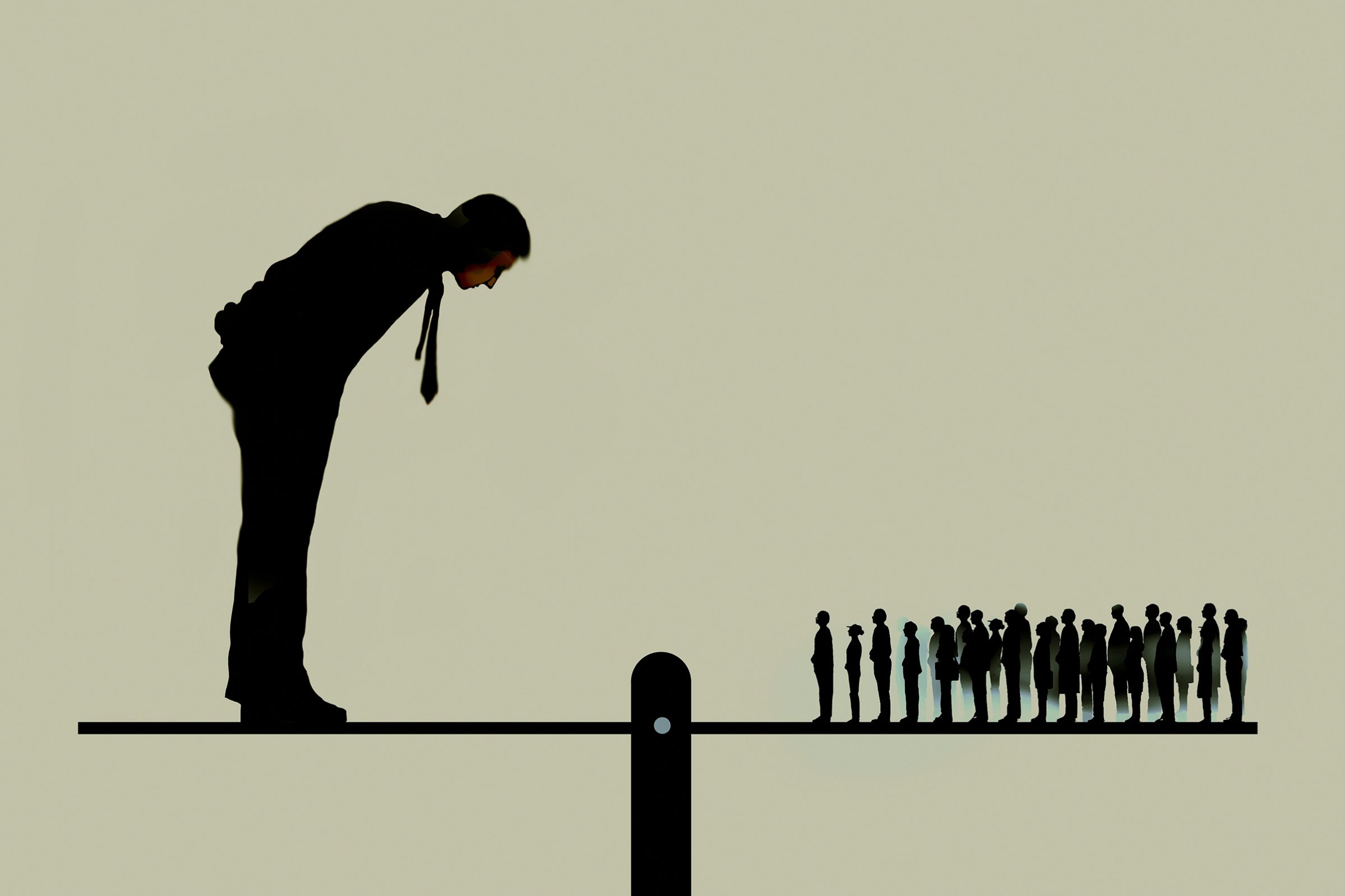

Harvard organizational sociology professor Frank Dobbin and others have since delved into why such programs have failed. Dobbin combed through thousands of data points and found that for white women and black men and women in management positions, it actually made things worse. That’s right: companies that introduced diversity training would actually employ more women and black men today if they had never had diversity training at all. He singled out three situations in which training is doomed to fail: when it’s mandatory; when it so much as mentions the law; or when it is specific to managers, as opposed to being offered to all employees. Unfortunately, he found, about 75% of firms with diversity-training programs fall into at least one of those categories.

Perhaps more to the point is the fact that the training infuriates the people it’s intended to educate: white men. “Many interpreted the key learning point as having to walk on eggshells around women and minorities–choosing words carefully so as not to offend. Some surmised that it meant white men were villains, still others assumed that they would lose their jobs to minorities and women, while others concluded that women and minorities were simply too sensitive,” executives Rohini Anand and Mary-Frances Winters noted in a 2008 analysis of diversity training in the Academy of Management Learning & Education.

Training done badly can also damage otherwise cordial relationships. Women and minorities often leave training sessions thinking their co-workers must be even more biased than they had previously imagined. In a more troubling development, it turns out that telling people about others’ biases can actually heighten their own. Researchers have found that when people believe everybody else is biased, they feel free to be prejudiced themselves. In one study, a group of managers was told that stereotypes are rare, while another group was told that stereotypes are common. Then both groups were asked to evaluate male and female job candidates. The managers who were told that stereotypes are common were more biased against the women. In a similar study, managers didn’t want to hire women and found them unlikable.

The evidence is damning. Yet companies continue to invest heavily in diversity training, spending, by one estimate, almost $8 billion a year. It has led to what the Economist dubbed “diversity fatigue.” In a recent article, the magazine suggested that 12 of the most terrifying words in the English language are I’m from human resources, and I’m here to organize a diversity workshop.

Now companies are searching for more effective, less infuriating alternatives. Take tech firms, which have come under fire for being among the worst offenders when it comes to bias. The irony is that they have also been at the forefront of devising new ways to combat it. Can they turn around a culture where sexism has not only been tolerated but in many cases celebrated?

I sat down with Brian Welle, director of people analytics at Google, who is tasked with helping lead the latest trend: unconscious-bias training. We all have prejudices buried so deeply inside of us that we don’t know they exist. Unconscious-bias training is supposed to arm employees with the tools they need to recognize it and neutralize these prejudices. His role, Welle told me, was to ensure that “every decision we made, from hiring to promotion to pay to performance, didn’t have an unintended bias” against women or other underrepresented groups.

Welle seized on an insight that has proved to be key for anyone who is trying to wipe out hidden biases: if we believe that everyone around us is trying hard to fight against those stereotypes and prejudices, we’ll do the same. Call it peer pressure, or call it a pack mentality. Whatever it is, it works. Our own biases disappear.

Welle and his team ultimately developed a workshop for Google employees that strives to mimic those conditions. In a typical session, he explains the science, so that employees can understand that yes, we’re all biased, and yes, we’re all trying to fight it, and don’t worry, it isn’t your fault. He focuses on four ways to “interrupt” bias, all of which boil down to one word: awareness.

He encourages employees to use consistent criteria to measure success and to rely on data rather than on gut reactions when evaluating others. He urges them to notice how they react to subtle cues. Finally, he encourages employees to call out bias when they see it, even if the culprit is their own boss.

To be sure, unconscious-bias training isn’t a cure-all. Last year, a male Google engineer penned an anti-diversity “manifesto” protesting such efforts, and later called the firm’s training “just a lot of shaming.” The company fired him–and he hit back in January, suing Google for discrimination against conservative white males. Google is also fighting U.S. Department of Labor allegations of “extreme” underpayment to female Google employees, which the company denies.

Still, Google’s seminar is a model that other companies have adopted. In just the past few years, this kind of training has exploded at companies across the country. At Google, about 75% of its 75,000 employees have taken the workshop, and in 2014 the company spent $114 million on its various diversity programs.

At least 20% of companies in the U.S. now offer unconscious-bias training, from the Royal Bank of Canada to consultants McKinsey & Co. (“We do that big time,” says its top executive, Dominic Barton) and defense contractor BAE Systems. Almost all of the big tech firms already offer it, including Facebook, Salesforce and VMware, with more joining by the day. By some estimates, 50% of all American corporations will offer unconscious-bias training in the not-too-distant future.

Undoubtedly, the popularity of these programs has soared in part because they intentionally don’t cast blame. The appeal of the training is that, unlike old-fashioned diversity training, it’s intended to be guilt-free. However, how much companies talk about equality and inclusiveness matters little compared with how they act. Incentives speak louder than any speeches by the CEO, or bias-training workshops, or posters on a wall.

For Google, as for others, one key incentive came in the form of family leave. In 2007, Google sweetened its leave policy, extending paid maternity leave to nearly five months, from three. The result was immediate. Attrition rates for women who had babies plunged by 50%.

That set off an arms race of sorts, with a growing number of tech firms offering gender-neutral paid parental leave to men as well as women, including Twitter (20 weeks), Etsy (26 weeks), Facebook (four months) and Change.org (18 weeks). Netflix and Virgin Management increased paid parental leave to a full year. The practice is now spreading beyond the tech industry to other industries as well.

The results of these changes are still unfolding. But they point to a hard truth. For men as well as women, it doesn’t matter how sincere companies are in embracing diversity if their own policies work against it–and in particular if they make it impossible to balance work with family. America lags far behind most industrial countries in this respect. It is the only industrialized country in the world that doesn’t offer paid parental leave. At least 96 other countries offer not only guaranteed maternity leave but paternity leave as well, including Gambia, Armenia, Belarus, Azerbaijan, Togo and Mauritius. Without broad policy changes that allow parents in every industry and at every level to have access to affordable health care and child care, the rest doesn’t matter.

From the book THAT’S WHAT SHE SAID: What Men Need to Know (and Women Need to Tell Them) About Working Together by Joanne Lipman. Copyright © 2018 by Surrey Lane Media, LLC. Reprinted by permission of William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com