Baby boomers and their successors may think they’re the first to be obsessed with precocious achievement, priming their children for the fast track even in utero. They’re not. American fascination with early off-the-charts mastery — its promise and its perils — goes back at least a century. Shirley Temple’s mother saw to it that her fetus had plenty of song-and-dance enrichment, and her wisdom on raising a star proved very popular with parents. Down the decades, different sorts of prodigies have claimed the spotlight as timely models, much as Shirley did. What better beacon of a brighter future for a country stuck in a Depression than a tiny expert hoofer who exuded confidence?

The young marvels heralded as offering lessons for the rest of us have done more than stun with their prowess. Their talents and circumstances have tapped into larger anxieties about social progress. Back in 1909, two super-precocious sons of Russian Jewish immigrants made news when they arrived at Harvard, years younger than WASP classmates with entitled airs. The campus prodigies’ fathers, impatient with genteel privilege, chalked up their math-minded boys’ feats to a vigorous striver’s credo that found an echo 100 years later in Amy Chua’s “tiger-mother” manifesto. Chua’s ideas about rearing musical virtuosi touched a nerve in a country caught up in debates over meritocratic pressures and privilege.

In between, other prodigies have won attention by seeming ready to lead where elders faltered. Sensitive literary girls in the war-weary 1920s offered uplift dreamier than Temple’s a decade later. Their remarkably accomplished poems and fiction, aglow with fresh imaginative genius, enchanted disillusioned grownups. Barbara Newhall Follett — whose novel The House Without Windows and Eepersip’s Life There came out in 1927, shortly before she turned 13 — evoked responses like this one from the critic Howard Mumford Jones: “She writes as though she were living in that serene abode where the eternal are.” Just after the launch of Sputnik, Bobby Fischer at 14 became the youngest U.S. champion in a game long dominated by the Russians. At the height of the Cold War, here was a balky American maverick — evidence of democratic drive — who could take on the Soviets.

Yet being ready to lead the way also meant being ready to leave their elders (not to mention more average youths) in the dust. Little wonder, then, that these emblematic prodigies have inspired ambivalence along with ambition. What is the price for speeding children onward? Doubts have kept pace with soaring aspirations. Surely, said critics a century ago, those Russian fathers were too bossy. Maybe those literary girls, some speculated, weren’t so innocent after all. (The work of Nathalia Crane, a published poet at 11, suggested an awareness of sex that fueled rumors of adult meddling.) Fischer’s defiant monomania already had many worried during his adolescence.

Alongside the shifting public debates, the underlying personal questions have remained much the same. Will such extraordinary children zoom smoothly onward to creative greatness as grownups, as enlightened mentors have hoped and claimed? Or will they burn out, deprived of a normal childhood? The simple answer is that of course paths diverge — sometimes starkly, as the Harvard boys showed. (One of them, William James Sidis, did his best to disappear from sight; the other, Norbert Wiener, went on to found the field of cybernetics.)

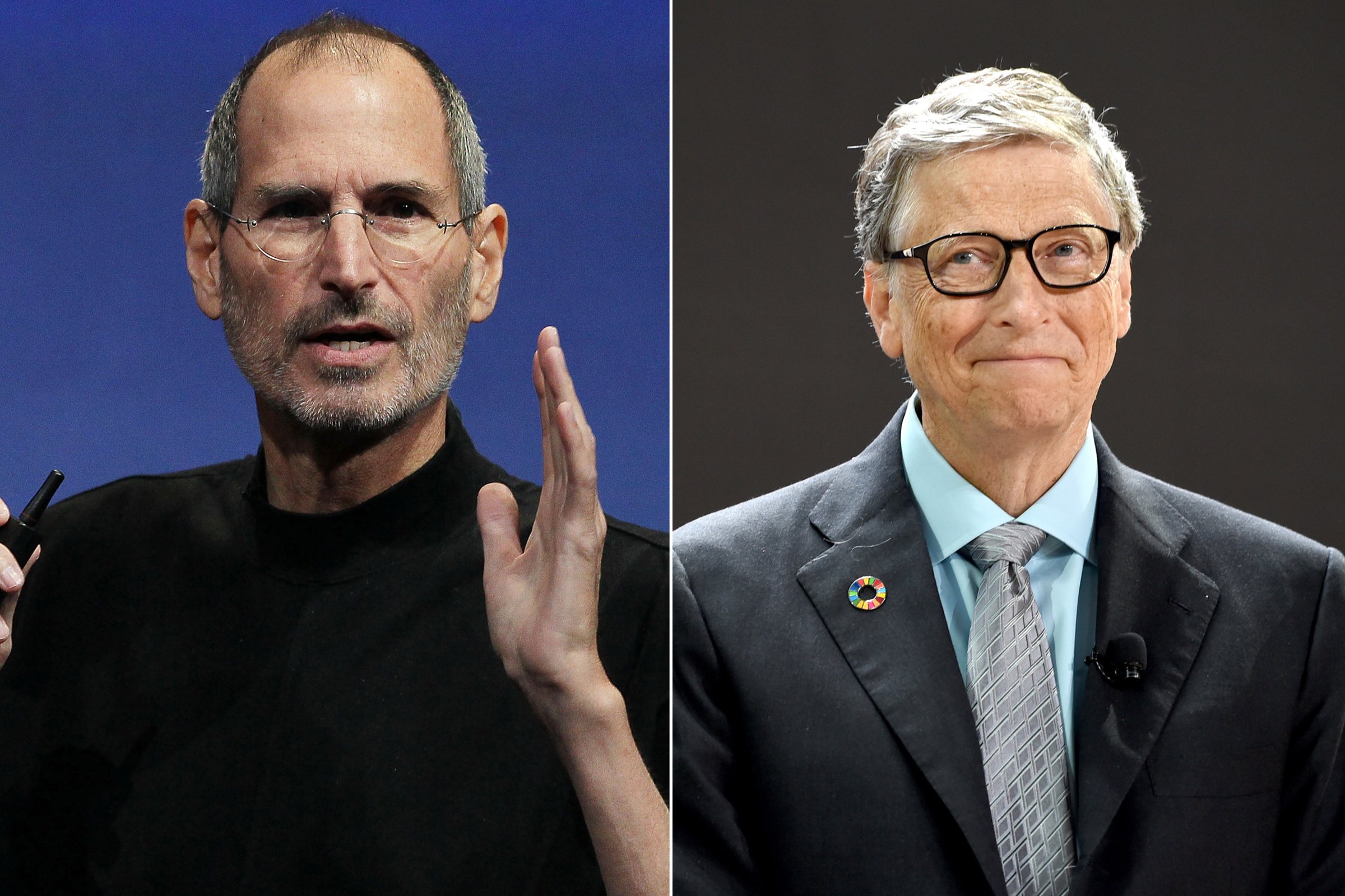

But the prodigies who put the biggest stamp on our times — brilliant boys of the boomer generation who fell in love with computers in the 1970s and 1980s — have disrupted the too-tidy dichotomy. They didn’t merely match adult mastery and meet exalted expectations, as prodigies have classically done. They were out in front, exploring new frontiers and brazenly being their own bosses. “I knew more than he did for the first day, but only for that first day,” said the math teacher who introduced Bill Gates and his high school friends in Seattle to a computer hookup.

On the East Coast, a psychologist named Julian Stanley at Johns Hopkins University inaugurated an ambitious talent search to identify middle school math whizzes by giving them the math SAT meant for 12th graders. Confident that swiftly gathering academic degrees was the key to efficient talent development, he launched accelerated classes and pushed for the highest-scoring among them to enroll early in college. What he didn’t predict as he ushered his pioneers onward in the 1970s was that a fascination with computers would propel plenty of math marvels out of the ivory tower. Young Steve Jobs told his parents he wasn’t interested in applying to Stanford, where he assumed students already knew their plans. He went to Reed College, but didn’t last long there. Gates and Mark Zuckerberg never graduated from Harvard.

These young upstarts rattled their elders, bucking notions of a streamlined, detour-free route to mature distinction. At the same time, the meritocratic push to spot and spur early talent meant new resources for them to take advantage of. Twenty years younger, Sergey Brin was a beneficiary in the late 1980s of the Center for Talented Youth summer programs by then thriving at Johns Hopkins, thanks to Stanley’s efforts. Brin had a precocious, accelerated college career — but then bailed on his PhD at Stanford. “The more you stumble around,” he said of his path to founding Google, “the more likely you are to stumble across something valuable.”

For parents feeling conflicted about the proto-prodigy paradigm of childhood, the mixed messages are useful. It’s hard to resist trying to extrapolate from current worries and hopes as we bend every effort to chart a promise-filled path for our children. But adults can always use reminders that their own experience hardly equips them to be experts on the future. And the truth is that the opportunities and obstacles likely to prove most important for our children, whether or not they soar at the start, are almost guaranteed to be the least predictable. However thrilling the chance to speed ahead can be, the chance to stumble has advantages of its own.

Excerpted from OFF THE CHARTS: The Hidden Lives and Lessons of American Child Prodigies by Ann Hulbert. Copyright © 2018 by Random House. Excerpted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com