Shortly after World War I broke out in 1914, two French artists could already predict that the conflict would take place on a scale unlike anything ever seen at that point. A tribute to it would, then, also demand an unprecedented scale.

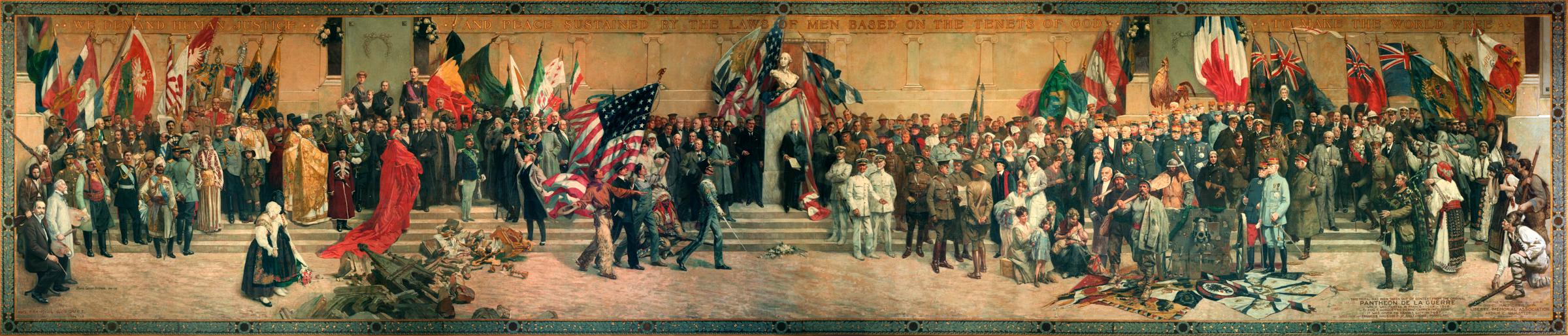

By the time the project they conceived to honor the Allies was completed, shortly before the armistice in 1918, more than 100 French artists — mostly older men who were not able to fight themselves — had worked on it. Dubbed Panthéon de la Guerre, the painting measured a whopping 402 feet around and 45 feet tall, and depicted approximately 6,000 heroes of the Allied war effort. It was billed as the world’s largest painting. (Whether it actually was depends on when and how exactly the comparison is made; one competitor for the title, for example, is the Atlanta Civil War cyclorama, which has been displayed at various sizes since it was completed in the 1880s but now clocks in at 371 feet by 49.)

But the version of the painting that exists today is not only smaller, but also takes a different perspective on the war. A full century after American forces first saw combat in World War I — on Oct. 21, 1917, in France — the modern Panthéon de la Guerre reflects late-breaking but crucial role of those troops.

After the painting was initially displayed in a dedicated structure in Paris, it went on tour. At the Chicago World’s Fair in 1933, a special building was constructed to display the massive mural. But, after it toured the United States in the years that followed, with the Great War fading somewhat in the minds of Depression-era Americans and a fresh war on the horizon, it wound up by 1940 sitting in a crate outside a Baltimore warehouse, forgotten. A local restaurateur named William H. Haussner — a German immigrant who in fact had fought for Germany in the Great War — purchased the painting at an auction for $3,400. In 1953, he finally unfurled his enormous purchase to see what it looked like.

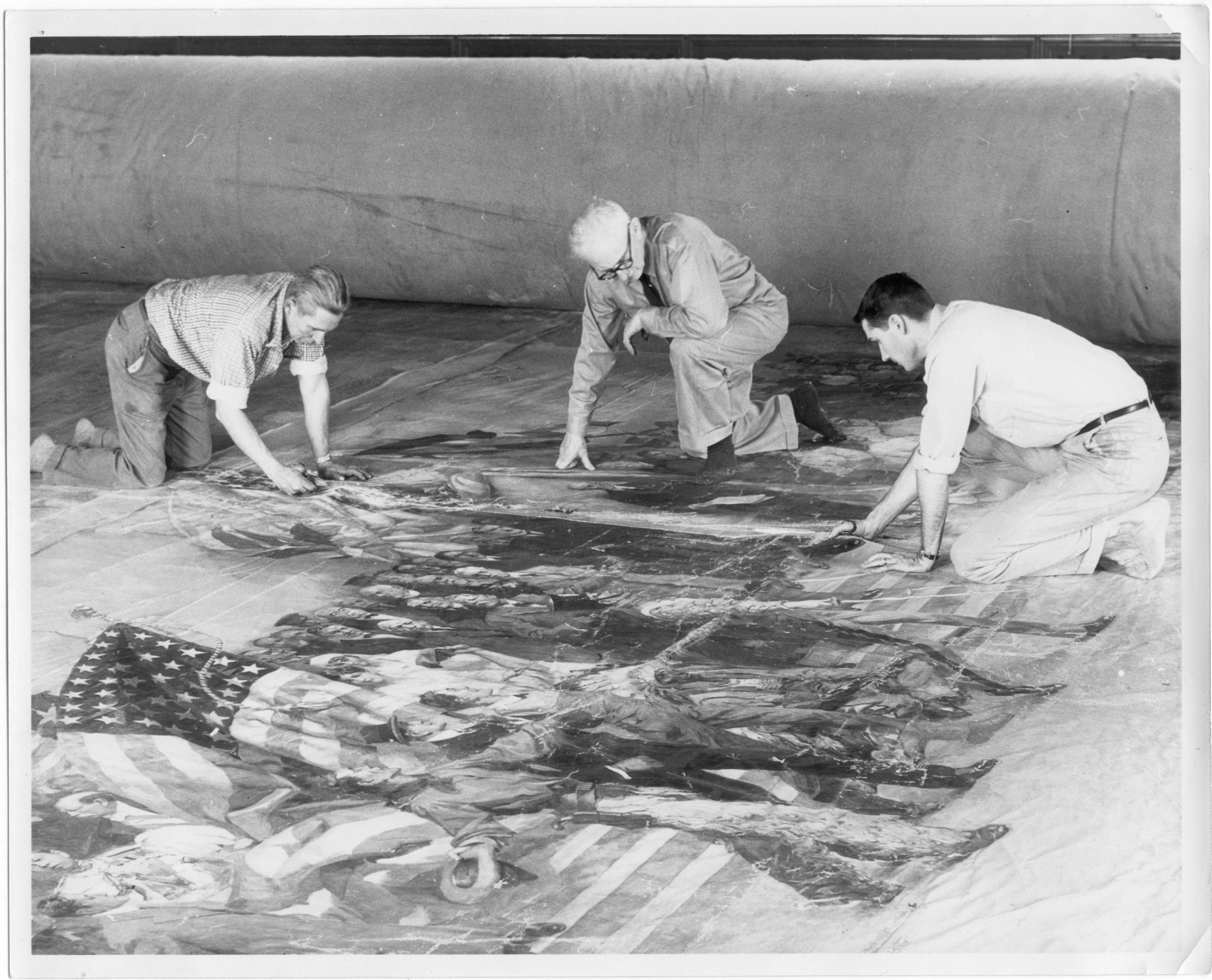

When he did, LIFE Magazine dedicated a short article to the steps necessary to inspect a 402-foot painting. And one of the people who saw that story was an artist named Daniel MacMorris, who had served in World War I and remembered seeing the painting in Paris. He tracked down Haussner and convinced him to donate the artwork to the Liberty Memorial Association, which was dedicated to commemorating World War I.

The only problem was that the Memorial, now the National World War I Museum and Memorial, couldn’t actually display a painting that large — and the painting wouldn’t have been in any shape for such a display, anyway.

“Because it had been outside, two thirds of the painting, the sky and the battlefield, had basically disintegrated,” explains Doran Cart, senior curator at the museum.

So MacMorris came up with a solution: using photographs to create a mock-up of the figures in the painting, he figured out a way to essentially cut up the painting and re-combine the most important parts into a smaller mural. Some of the scraps he gave back to Haussner and others went to his assistants. Others went in the trash. And the main painting, its area reduced to about 625 square feet, still hangs at the Memorial.

“The only push-back MacMorris got was from Haussner, but he eventually convinced him this was the only way it would be preserved,” Cart says. “It didn’t change the importance of the painting as much as it changed the size of it.”

The finished version did change something else, too. Whereas the original artists had been French — and had been working on the painting for years before the U.S. entered the war they were depicting — the Panthéon was now going to live at an American memorial to the war. Accordingly, MacMorris added a few American heroes who hadn’t made the cut, and if you look at a modern photograph of it (such as the one above) the American section is centrally located.

In some ways, however, the changing look of the painting is in keeping with part of its original message: the idea that, even in the midst of world-changing war, there was still a place for art. The world did not freeze while the fighting happened, nor has it frozen in the years since. As Cart puts it, “Life did go on.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com