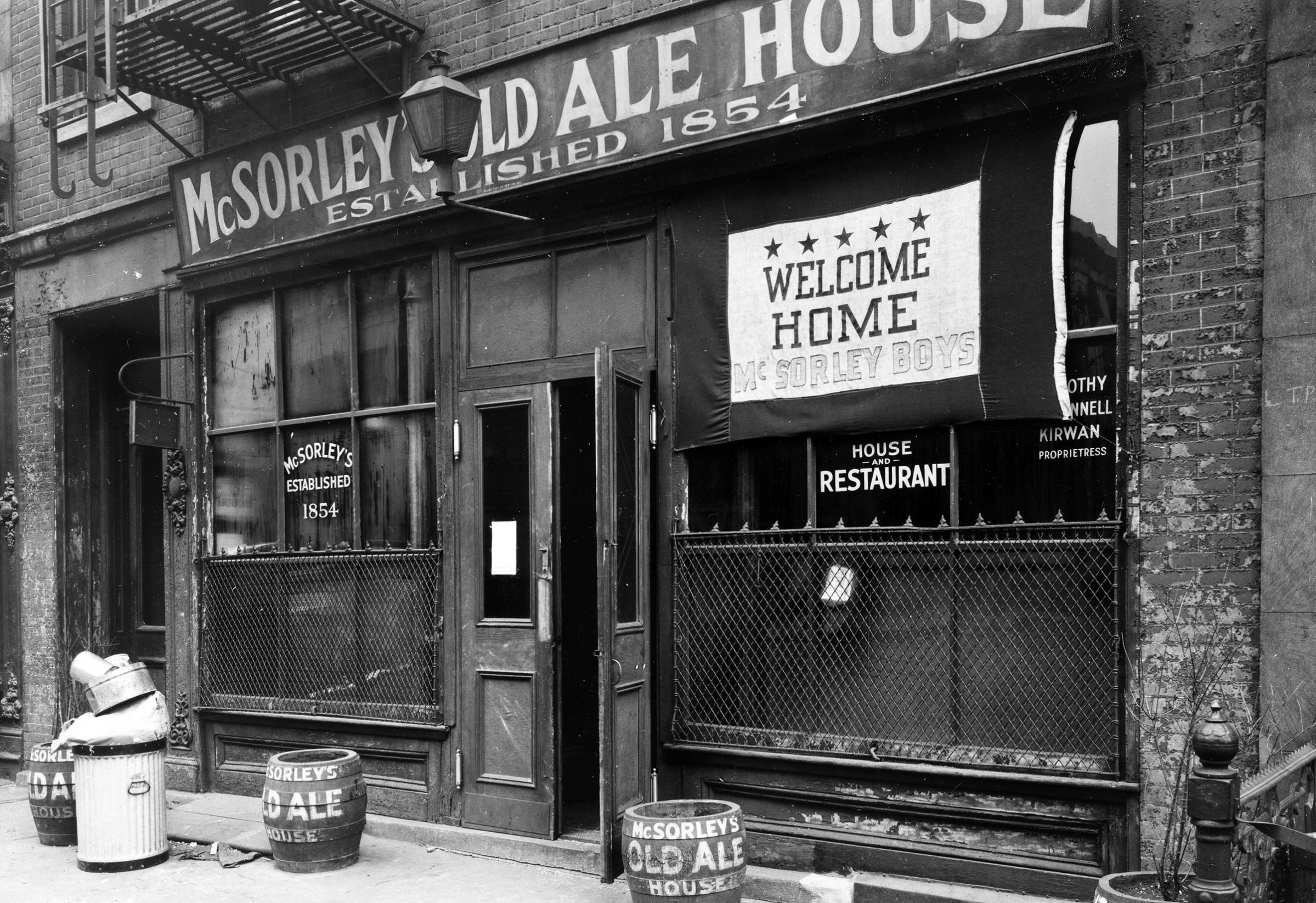

Todd Webb’s New York didn’t disappear all at once. It’s impossible for me to look at these pictures and not think of my arrival in New York from the Midwest as a young man in the late 1960s, when much of the city Webb had photographed two decades earlier was still present. The subway cost twenty cents, and there were still cushioned seats and porcelain-covered handholds for the straphangers (a word I first encountered in print and pronounced as “straffindger” until it provoked giggles from a colleague). The Third Avenue El had come down several years earlier, but many of the Irish bars and small-scale retail and service shops that had grown like mosses in the shadows of its tracks were still present. Chinese food was still Cantonese (the chop suey parlor would have been right at home in 1960s New York). On West Forty-Third Street, in the building that had housed the offices of the New Yorker for more than three decades, I found — and cherished — a small shop called Music Masters, which sold hard-to-find classical albums, including many of its own manufacture that were available nowhere else. Every block, it seemed, had a store like that, and it was impossible for a newcomer not the embrace the old city that, for me, still exists in black-and-white memory. It was swiftly receding, but its grip was — and is — strong.

In Webb’s time, particularly in the richly productive period that he spent in New York immediately after World War II, the city had not yet begun its cosmetic reconstruction, much less the more profound transformation yet to come beneath the surface of its skin. In fact, the face of Webb’s city had not changed much since the early ‘30s. Because of the intervention of depression and war, the city’s only private high-rise construction between the completion of the Empire State Building in 1931 and the arrival of the Universal Pictures Building on Park Avenue and Fifty-Sixth Street in 1947 was at Rockefeller Center. The “Empty State Building” earned its nickname from the effects of the Depression on its rental program. Rockefeller Center avoided similar sneers only because the man who built it could afford to charge cut-rate rents, and wait until good times returned.

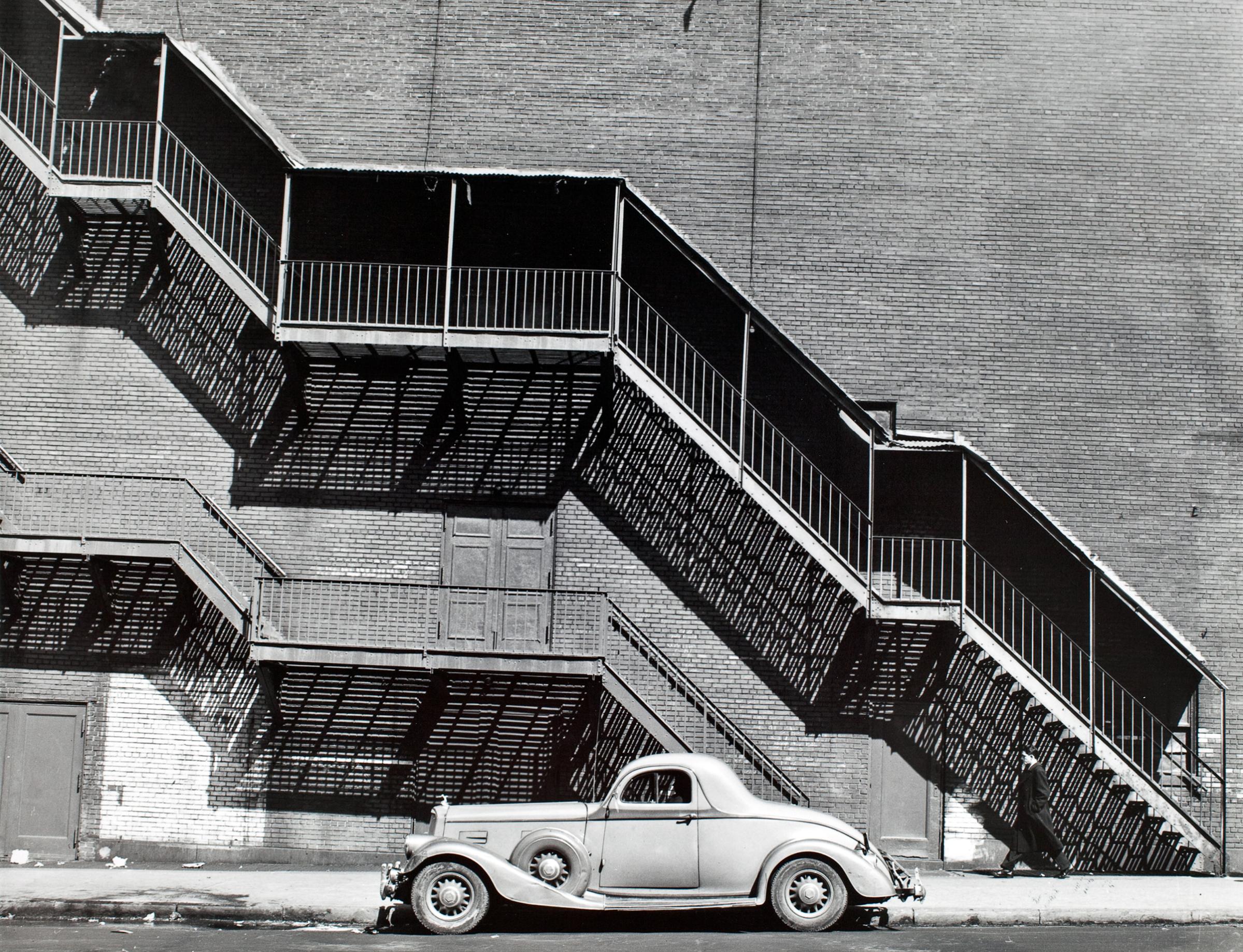

In the years immediately after Webb moved to the city in 1945, the postwar boom had barely begun to paint its changes on the city’s face. Even over the next several years, the glass-and-steel curtain wall buildings of the International Style had yet to transform Manhattan’s avenues, obliterating the extensive, low-rise city that had not given way to the building boom of the 1920s. The balance began to tip in the late 1950s with Mies van der Rohe’s epoch-defining Seagram Building on Park Avenue. Until then, the social and commercial worlds the new towers would soon both signify and glorify hadn’t arrived either. My guess is that Todd Webb would have been oblivious to the rush of the new. Walking New York’s streets day after joyous day (“I see wondrous things!” he told his diary), Webb found his affinities in a city that remained intensely human — small-scale, apprehensible, immediate.

Webb was drawn to the parts of that city that remained humble in their pretensions and their ambitions. To me, this is what separates Webb’s New York from the city his contemporaries saw. The celebrated Arthur Fellig, a.k.a. Weegee, whose connection with the city’s underside was enduring, instinctive, and at times exploitative, would take his Speed Graphic to the doors of the Metropolitan Opera, even if only to satirize the bejeweled and behatted heiresses, heirs, celebrities, and socialites who frequented the place. In all of Webb’s pictures, this New York is more than invisible: it simply doesn’t exist.

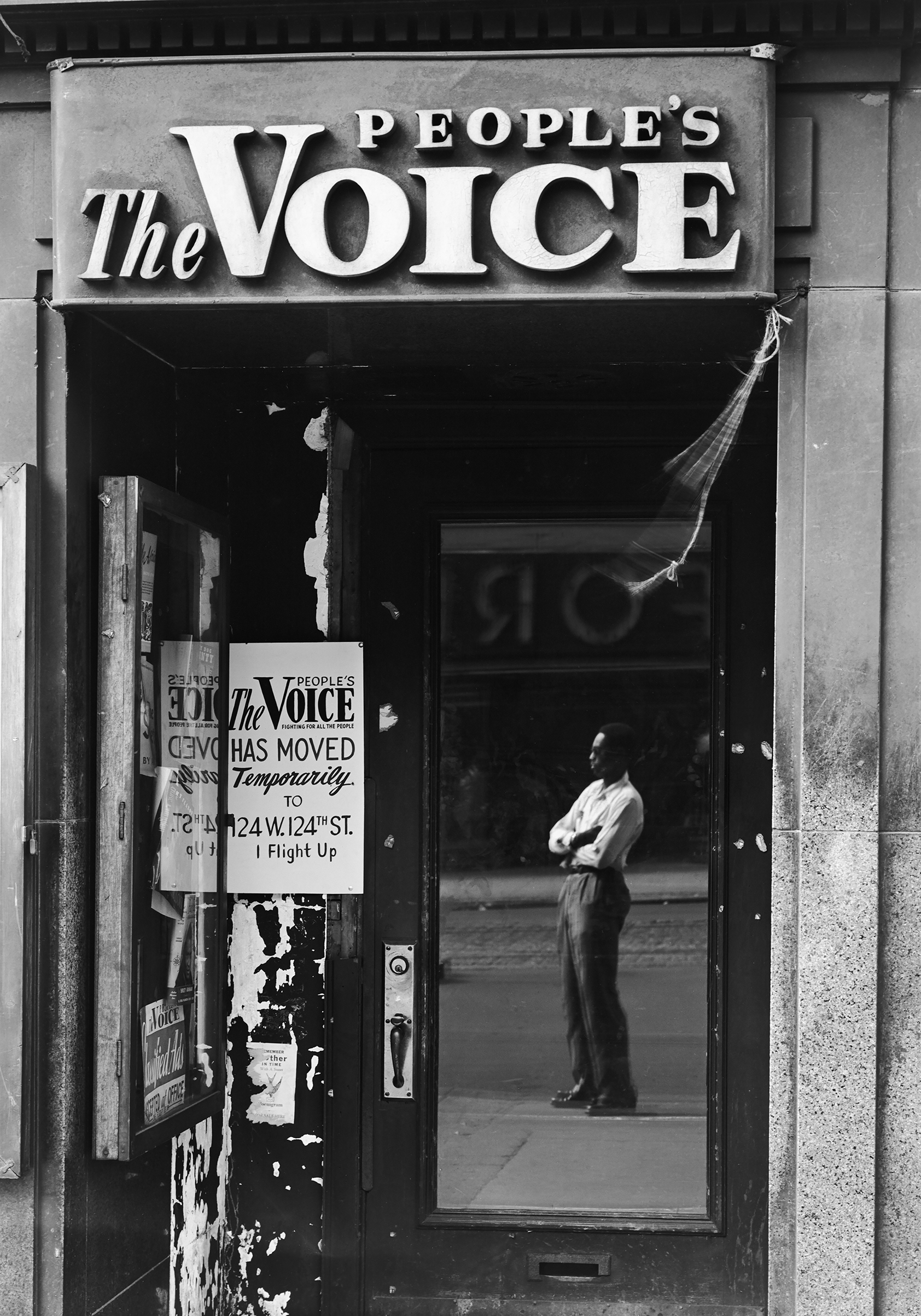

Instead he revealed a workaday city inhabited by people who ate at luncheonettes or bought their provisions from street peddlers, who labored in its small shops and its still-thriving garment factories (the view down West Thirty-Seventh Street suggests how vibrant that industry still was). Except for the material wealth implied in his magisterial views of the skyline, Webb’s New York is not even remotely upscale (a neologism that itself didn’t come into its current meaning until 1966). Neither had gentrification begun, or even been conceived (it didn’t enter the language until the mid-‘70s). His New York is bustling — look particularly at the vivid life he found on 125th Street in Harlem — but there’s nothing either aspirational or demonstrative about the bustle: these are real people, living real lives.

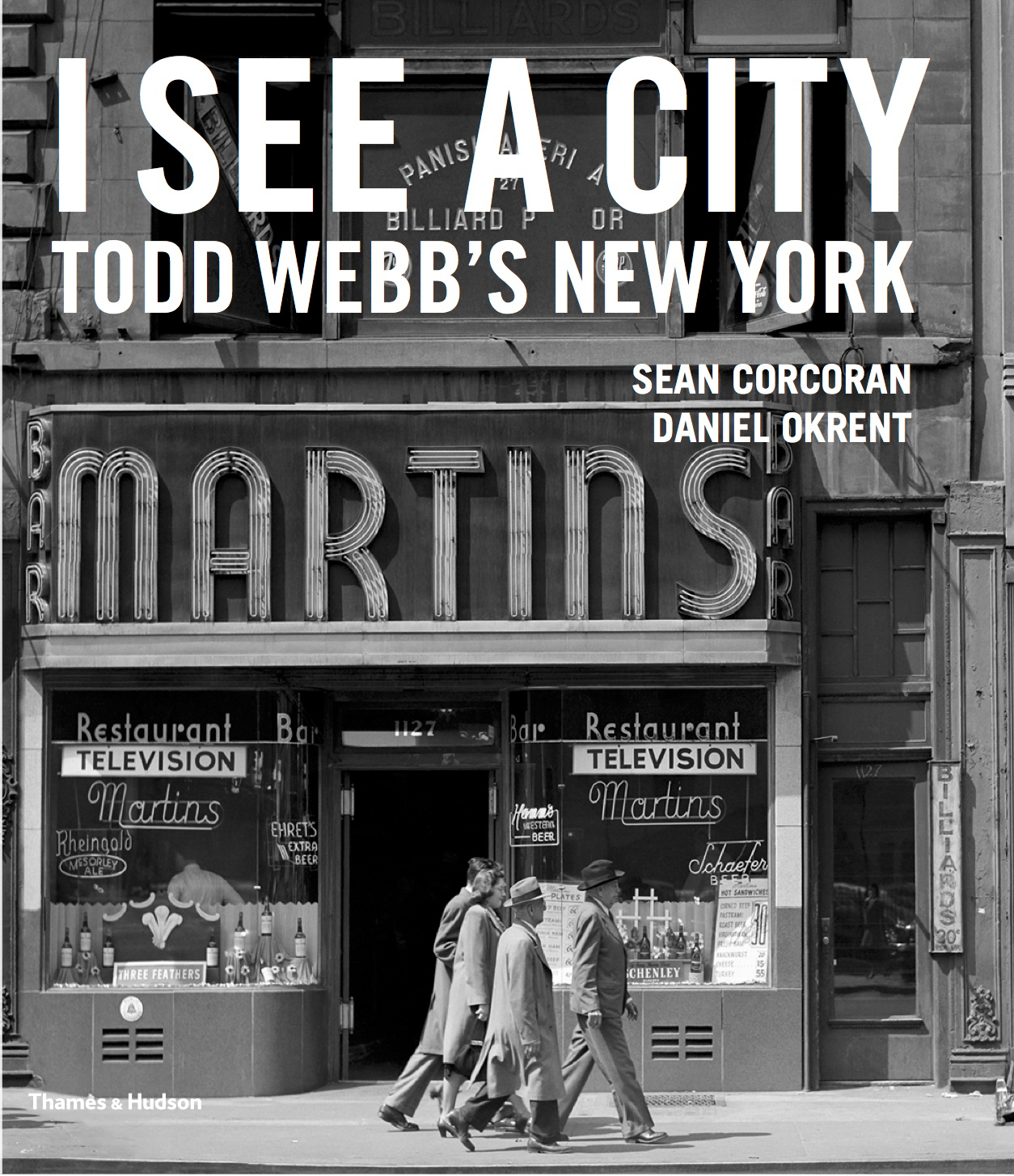

Text and images excerpted with permission from I See a City: Todd Webb’s New York (Thames & Hudson, November 2017). The book and Todd Webb’s photographs will be celebrated at The Curator Gallery in New York City on Dec. 13.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com