It doesn’t start with love. If you want to live in a great town, but you’re not quite there yet, you don’t just start to build that town with love, peace, civility, or morality. You start with a hill. You say to yourself, That hill, off the side of the high school, would be perfect for sledding. I know someone who could mow it with his riding mower. You call that guy and ask. He says, “Sure.” On an early Saturday morning in late September when the streets are empty, he drives over on the main roads and mows the hill. You hand him a coffee and tell him your idea.

He says, pointing, “After it snows, you should get someone to just tamp it down, establish the track so the kids don’t end up in the junk trees there.”

You imagine thorny branches, kids with broken legs and stitches.

Lawsuits, condemnation. Yes. Tamping. Tracks. Good idea.

“I know a guy with a plow,” this guy says. “I’ll get him to make a track when the first snow falls.” The snow falls, and the plow guy comes. He makes four parallel tracks and sends his niece over with a sled. You invite your kids and some of their friends to take a maiden run. All parties inform you that it’s awesome. By afternoon there are twenty kids. The parents talk while the children sled.

A woman shyly approaches and says, “I’m on the PTA, and I was wondering if I could sell hot chocolate for a suggested donation. We’re trying to fund some enrichment programs.” “Anyone can do anything,” you say. “I have no claim on this. I just knew a couple of guys.” Over the course of the winter, the PTA makes eight hundred dollars on hot chocolate and coffee sales. When people see it’s for the PTA, they round up their donations as generously as they can. It’s not a wealthy town, but still.

By the next year, the mowing guy knows a tree guy who’s cleared away the junk trees to make more room for sledding. The PTA woman who sold the hot chocolate has been talking about what the school is up to, what it could use. People offer to teach after-school programs and make school visits. One woman can come in to sing; would that be helpful? One woman has a python. Should she bring it? A librarian asks what the library can do. By the next year, the sledding hill is the place to go. People bake for the PTA table, and a local farm is the milk sponsor. The PTA has accumulated a fleet of volunteers who tutor at the school. The woman from the PTA is dating the guy with the mower. The library and school are coordinating events. Someone has started a small concert and reading series at the base of the sledding hill in the summer because the slope of the hill is like a natural amphitheater.

Next year someone wants to run an outdoor film series. There’s talk of a small community herb garden, and someone has approached the guy with a plow about starting a tool library. He says he’ll talk to the gal at the VFW Hall. Maybe they could do it there. That’s when a father from another town, watching his kids speed down the hill, turns to you and says, “This is a great town. I wish we lived here.”

What this town is building, aside from new trails and a better school, is positive proximity, or a state of being where living side by side with other people is experienced as beneficial. I have been seeing this phenomenon of town building for more than twenty years.

Someone starts something. Others join in. And then everything starts to shift into more clarity, more resilience, more goodwill and more pride. Libraries find their way into the digital age. Schools improve. People actually sit and eat ice cream on the benches eerily empty for years.

I’ve seen the power of positive proximity firsthand in hundreds of towns such as Lowell, Massachusetts, hit with the twin degradations of industrial downturns and a crack epidemic in the 1990s. I saw it in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, where, after the R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company left the state in 1995, the promoters of my near empty concert were vowing that they would revive the city through the arts. Good luck with that, I thought. They did have very good luck with that.

I didn’t understand the power of the positive proximity I had witnessed until I was having dinner at my friend Kate’s house in Charlottesville, Virginia. Her husband, Hal Movius, who writes books about conflict resolution, filled my wineglass and asked, “What do you think determines the relationships we’ll have in our towns?” Hal loves to pore through Harvard studies and explain them to dinner guests.

I said, “Values.” No.

“Politics?” No again.

“Hobbies?” Wrong.

Hal said, “Proximity. That’s all.”

I disagreed. Into my mind came full-blown images, provided by news headlines, of neighbors fighting over parking spaces and fallen tree branches. I’d just heard the story of a company that could identify DNA in dog poop so people could know the genetic fingerprint, as it were, of the anonymous offenses in their courtyards. Early clients were co-op associations.

But then I realized with a jolt the study Hal was referring to was right. When people transcend the myth that proximity means conflict and invasion of privacy, they gravitate toward finding ways to integrate the talents and skills of their community members. Not only that, after people discover each other in the commons of town, more connections are made, and the next thing you know, you’re Lowell, Massachusetts, that small city that had a terrible drug problem but now has five museums, a popular minor league stadium and team, and a free concert series that attracts thousands of families every summer.

I see towns and cities as being like people who build some framework of identity that allows them to assert themselves, do good work and know where they stand. I find myself almost befriending them, wanting to introduce them to each other. Peoria, Illinois, have you met Cedar Rapids, Iowa? Seattle, Washington, you have some interesting things in common with Asheville, North Carolina. Gardiner, Maine, I think Dover, New Hampshire, could provide some helpful insights as you continue the winning streak you’re on with your downtown.

Over time I have detected certain simple patterns that facilitate positive proximity. There are three essential categories for building and growing it.

First, there are spaces, indoors and out, that naturally maximize the number of good interactions in a town. Generally these spaces have some individual character while still being open enough to accommodate the desires and interests of diverse citizens.

Second, there are projects that build a town’s identity — socially, culturally, and/or historically — helping them become . . . themselves. These projects bring out the advantages of proximity by attracting the passions and skill sets of people who are like-minded in some ways but very different in others, cross-pollinating abilities and personalities.

Citizens tend to see past their partisanship and biases when they’re trying to accomplish something they can’t do alone, such as plant a community garden or start a riverfront music series. These projects remind us, whether we’re building the scaffolding, installing the floor joists, or attending events in the finished barn, that collective pursuits are achievable. Creating or discovering a town’s identity can be the ongoing proof that positive proximity exists. You can feel it in the air.

Third, there is the abstract quality that I call translation. Translation is essential for positive proximity to take root and grow. Translation is all the acts of communication that open up a town to itself and to the world. Translation is not to be mistaken for civility. Translation includes a tacit commitment to facilitating all the variegated voices and personalities in our towns. Whether it’s the shy math whiz student who has an uncanny technique for explaining algebra to struggling students; the eccentric obsessed with cleaning up the local cemetery; the commuting banker dad who wants to learn how to coach seven-year-olds in soccer (benevolent dictatorship all the way!); the neurotic, though brilliant, lawyer who steps in to talk her town through a zoning issue, translation is the ability of a place to incorporate every willing citizen’s contributions, and in so doing, find ways to make life more interesting, welcome the outside world and provide stability for those who need support, because strong positive proximity means that no one gets left behind.

When towns have any or all of these components of spaces, identity-building projects and translation, they grow. They become more self-determining, and they thrive.

No one starts with the word “love,” but in so many towns I’ve visited, something happens after the sledding hill, the playing fields, the concert series and the local festival start opening up a world of local relationships. There is a warmth and wonder in the expressions of the residents. They say, “I love it here. I belong here. I can’t imagine living anywhere else.” Some people even go from saying, “I live here” to “I’m from here.”

There is one preliminary question that will help you gauge the positive proximity in your town and your relationship to it. You probably know where you live, but where are you from, and where do you belong?

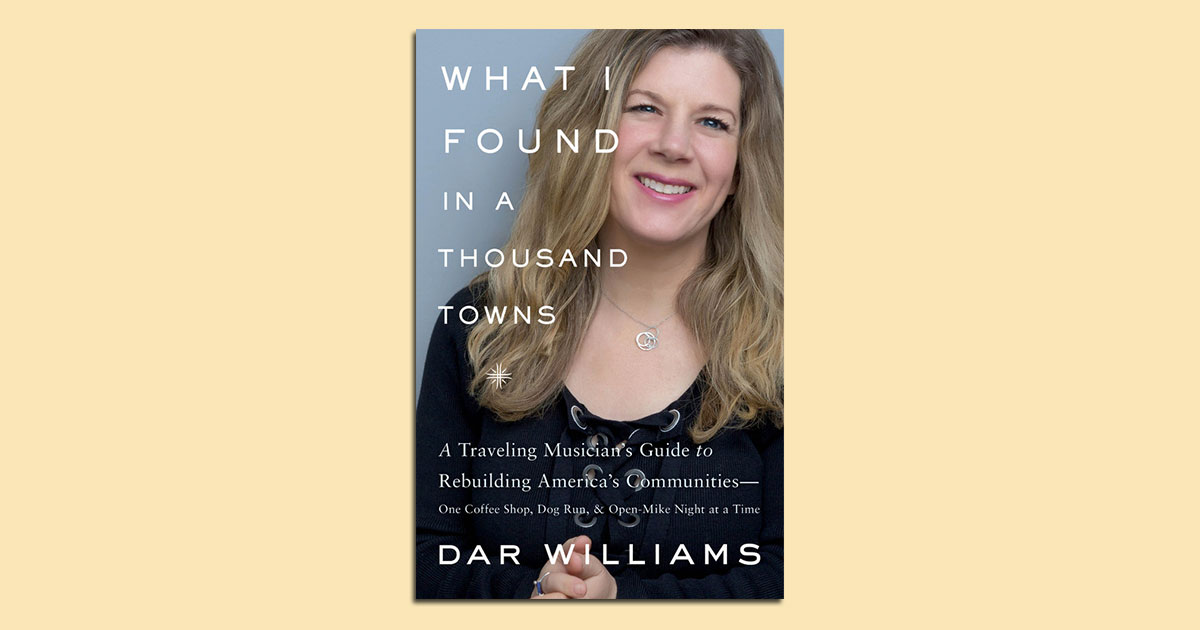

Excerpted from the book What I Found in a Thousand Towns by Dar Williams. Reprinted with permission of Basic Books.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com