Milestone moments do not a year make. Often, it’s the smaller news stories that add up, gradually, to big history. With that in mind, in 2017 TIME History will revisit the entire year of 1967, week by week, as it was reported in the pages of TIME. Catch up on last week’s installment here.

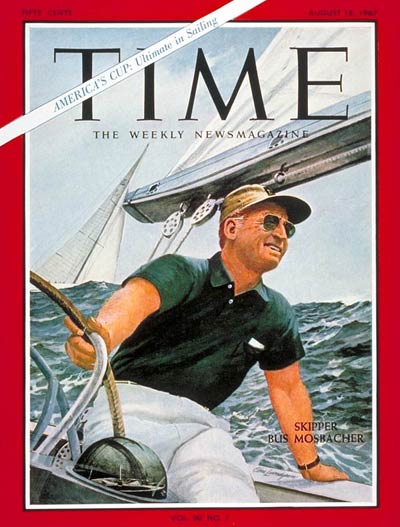

As an interest in sailing spread throughout the U.S.—well, at least to those places with access to water—TIME caught up with the man leading the charge: “Bus” Mosbacher, who was about to race for the America’s Cup, “the closest thing to a Holy Grail in sport.” The contest had been going on for more than a century, the cover story explained:

The contest, not the old Victorian silver ewer, is the thing. In the demands it makes on boat and man, it is the ultimate, the very pinnacle in yachting. What started 116 years ago as a gentlemen’s lark, has become a proving ground for technocrats, a vast public spectacle, an affair of national pride, purpose and prestige that so far has cost the competitors, winners and losers combined, an estimated $50 million—with no guarantees on the investment except that somebody would win and somebody else would lose.

No such harsh terms faced John C. Stevens, a founder of the New York Yacht Club, when he sailed his new, 102-ft. pilot schooner America to England in 1851 to do battle with the Royal Yacht Squadron in a race around the Isle of Wight. The original price of the America was to be $30,000, but her builder had to knock her down to $20,000 because she did not prove the fastest boat in the U.S. Against the British, though, she was worth every penny. Near the finish line, aboard her royal yacht, Queen Victoria herself waited to present the “100 Guineas Cup” to the winner. “Sail ho!” came the cry from the bridge. “Which boat is it?” demanded the Queen. “The America, Madam.” Said Victoria: “Oh, indeed. And which is second?” There was a pause while the signalman’s glass swept the horizon. “I regret to report,” came the halting reply, “that there is no second.” At least not that eyes could see —the British were so far behind.

That set the pattern. Over the next 86 years, the British tried 14 times to win the Cup, the Canadians twice, and all their efforts met with defeat at the hands of Yankee design, tactics or luck. “I willna challenge again. I canna win,” sighed Glasgow Tea Baron Sir Thomas Lipton in 1931, when the fifth of his Shamrocks suffered the same inglorious fate as the previous four. Next came T.O.M. Sopwith, famed stunt flyer, hydroplane racer and aircraft builder—and with him the grand era of the J-boat, majestic, 130-ft.-long monsters with 165-ft. masts and clouds of sail, crewed largely by professionals and capable of speeds up to 18 knots on a close-hauled reach. No faster or prettier oceanracers ever existed—or ever will again. In 1937, with Europe in turmoil, Commodore Harold Vanderbilt’s Ranger, designed by Naval Architect Olin J. Stephens II, even then a brilliant, but little-known youngster, sank Sopwith’s Endeavour II in four straight races, and the America’s Cup was bolted into a trophy case in the New York Yacht Club—there to remain, virtually forgotten, for most of a generation.

Mosbacher had announced his retirement after 1962, when, as skipper, he captured the cup. It was, for him, a matter of that long history. He had proven himself once, and it seemed folly to go again and risk being the one who broke the American streak with the America’s Cup. But it had turned out that he couldn’t resist, and now he was back.

Spoiler alert: Mosbacher would win, and U.S. domination in the race would last until the 1980s. (Perhaps also of interest: the editors helpfully provided this sailing glossary, for all the landlubbers out there.)

After the riot: In the aftermath of the riots that had swept American cities that summer, the political tide was turning in the direction that many in those cities had feared. Even though local government on both sides of the aisle seemed to be responding to the unrest by trying to address some of the grievances aired, Congress was looking at strong anti-riot measures that would impose harsher penalties on those who participated in any such future events.

For the birds: This gem deserves to be quoted in full:

The way Director Roger Vadim, 39, planned it for his movie Barbarella, giant fans would blow 2,000 wrens into a cage occupied by Wife Jane Fonda, 29, exciting them so much that they would peck off her clothes. For four days the fans whirred, birds swooped, Jane emoted—but nothing happened. In desperation, Vadim jammed birdseed inside her costume and fired guns in the air, which bothered the birds not at all but drove Jane off to a hospital with a fever and acute nausea. After three days of rest Jane returned to work, finally finished the scene with the aid of even larger fans and a flock of peckish lovebirds. It would all come out onscreen, said Roger, as a “whimsical, lyrical outlook toward sex in the year 40000.”

Behind bars: This piece from the Law section goes inside the Mississippi State Penitentiary at Parchman, the only U.S. prison that officially allowed conjugal visits at the time. About 400 inmates—married men who met certain behavioral and sentencing standards—qualified for twice-monthly access to the private rooms provided by the prison for that purpose. As of last month, after a period of time during which the Mississippi practice spread to states throughout the country, only three states allowed overnight family visits for prisoners.

Programmers needed: As computers proliferated, the industry was beginning to bump up against a problem that might ring familiar for employers today—a shortage of coders. By TIME’s count, there were at least 100,000 men and women employed as programmers for the 37,000 computers in the U.S., but at least 50,000 more of them were needed.

Great vintage ad: This ad for razor blades shows how much (and how little) shaving technology has changed in the last 50 years.

Coming up next week: A different side of Vietnam

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com