When the civil-rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in 1968, he was already a national icon. But it would take nearly a decade more before he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor. He was given the posthumous medal by President Jimmy Carter on July 11, 1977 — precisely 40 years ago Tuesday — for being, in Carter’s words, the “conscience of a generation” who “made our nation stronger because he made it better.”

Carter’s decision to give King the medal came nearly a decade after the activist’s death, but the timing made sense in the context of American politics at the time. The award was part of Carter’s first round of Presidential Medal of Freedom selections, and many saw it as one way for Carter — who had won more than 80% of the African-American vote in 1976 — to acknowledge the voters who put him in office in the first place.

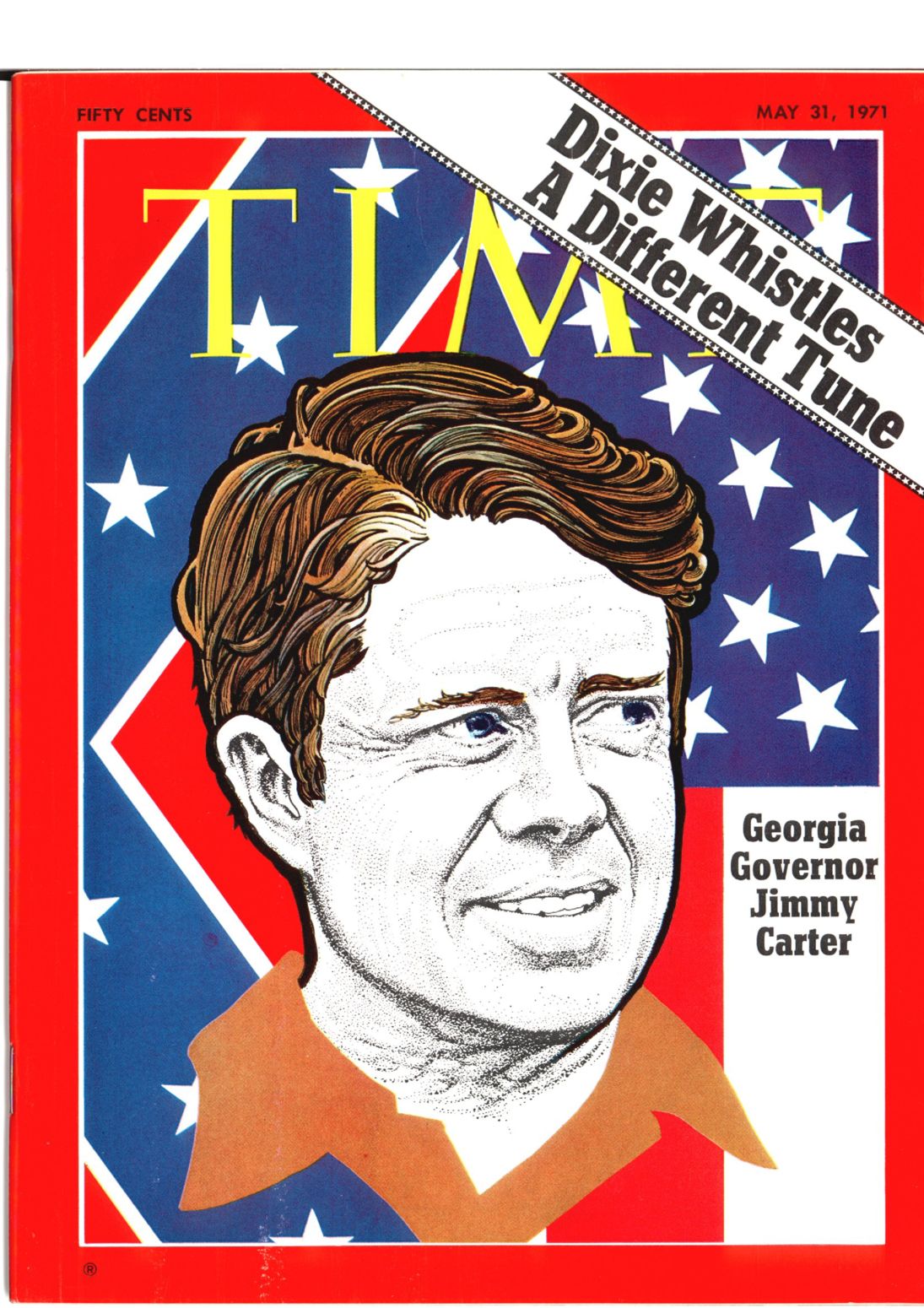

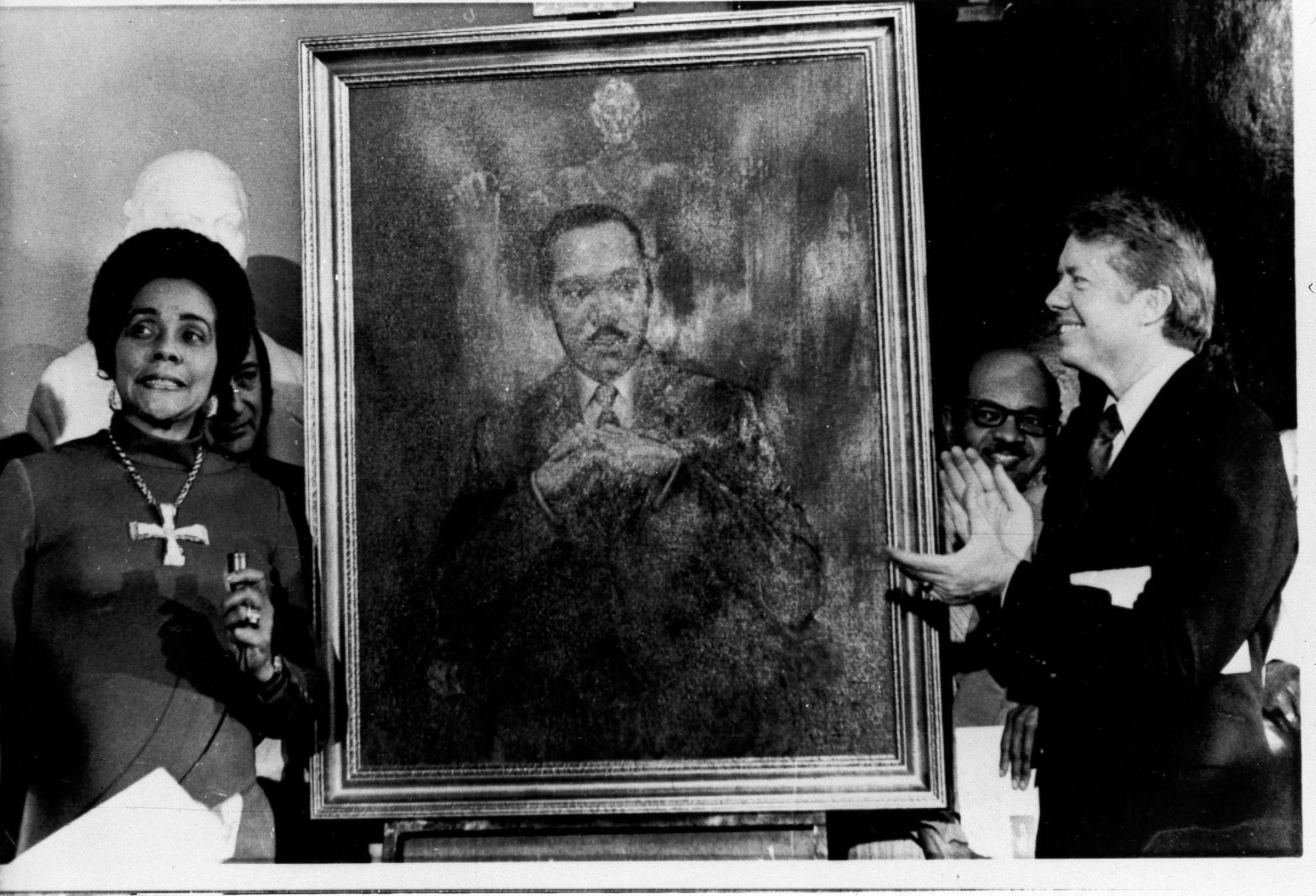

Not that his outreach to African Americans started with the election. He had become famous for declaring that “quite frankly that the time for racial discrimination is over” during his inaugural address as the governor of Georgia in 1971, and unveiled a portrait of Martin Luther King Jr. in the Georgia state capitol building in 1974. He was also the first Georgia Governor to appoint African Americans to many prominent state posts. “Nowhere can the promise — and the serious problems — of the emerging South be seen as readily as in Jimmy Carter‘s state of Georgia,” TIME declared in a cover story on how Carter represented change in the region.

When Carter ran for president, he was predicted to easily win the black vote, thanks in part to ties to King’s life and legacy. Andrew Young, the Georgia Congressman and former aide to Martin Luther King Jr., became a key liaison to black leaders, regaling church-goers with stories about how Carter lived next door to a black bishop whom he prayed with. The Rev. Martin Luther King Sr. delivered invocations at the Democratic National Convention. And, as now-Rep. John Lewis, who then ran the Atlanta-based Voter Education Project, pointed out to TIME, black support for Carter was a vote against one of his primary challengers, the segregationist former Alabama Governor George Wallace.

So it was no surprise that when Carter won the election, black leaders and the press were quick to look to the work of Martin Luther King Jr. “I wish — Lord, how I wish — Martin were alive today,” Lewis said afterward. “He would be very, very happy. Through it all, the lunch-counter sit-ins, the bus strike, the marches and everything, the bottom line was voting.”

And Carter acknowledged on myriad occasions, including upon receiving the Nobel Peace Prize, that his political career was made possible by the work of civil-rights leaders like King.

But the Presidential Medal of Freedom wasn’t just about acknowledging work that had been done in the past. Accepting the award, the activist’s widow Coretta Scott King pointed out that the decision to give her late husband the medal was symbolic of a national shift that, she hoped, would continue into the future. “It is highly significant,” she said, “that you, Mr. President, a white Southerner, would become the first American President to recognize the importance of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s contributions to the human rights movement in this country.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com