Ashley Hurteau knows she’s not your typical public-health advocate.

In and out of jail, a recovering heroin addict equipped with few credentials beyond her personal story, the 32-year-old New Hampshire resident says it took waking up to find her husband dead from an overdose to put her on the path toward recovery. That and health care. Which is why, at a public forum on June 23, Hurteau stepped up to the microphone and pleaded with her state’s two U.S. Senators to fight with everything they had to block Republican plans to gut health care programs like the one she credits with saving her life.

“I got back custody of my son two weeks ago, and I’ve been sober 17 months,” Hurteau said as more than 200 people watched that afternoon in a law-school classroom in Concord, N.H. “Medicaid expansion is really about opportunity, the opportunity to get sober, to move on and to live a clean life.” She was there as a success story–and a warning about what could go wrong if someone like her didn’t have access to care during a time of need.

But scaling back Medicaid–the 52-year-old federal health care program for the needy–is exactly what Senate Republicans are vowing to do when they return from the July 4 holiday. It is a huge risk for the GOP and helps explain why Mitch McConnell postponed a vote on his party’s latest plan in the final week of June. The public defections betrayed deeper problems for the bill, which will be weaponized against its supporters in coming elections.

When it comes to changing Medicaid, the Republican plan has two main parts. First, it would roll back programs that allow states to enroll residents who earn wages slightly above the poverty line in state-run Medicaid programs. That alone has boosted the rolls of people with health coverage by more than 14 million, allowing, for instance, families of three who earn $27,000 to qualify for free or low-cost coverage.

The second part would cap federal funding that states use to underwrite their Medicaid programs, which roughly 76 million Americans rely on for health care. While each state’s program goes by a different name–like MaineCare, Healthy Louisiana and New Jersey FamilyCare–their collective reach is epic. Nearly half of all babies born in America are covered by Medicaid, as are close to 40% of all children and two-thirds of all nursing-home residents. Roughly 9 million more Americans who are blind or disabled, including those born with Down syndrome or cerebral palsy, also rely on Medicaid for coverage. Most children’s vaccines are covered, and adults in many places get their flu shots at the corner drugstore for free as well.

Normally, making entitlement cuts of this size is political suicide, but these are not normal times. The House has already passed a version of these cuts. McConnell postponed a Senate vote when conservatives and moderates rebelled at the pace and terms, including the lack of funding for opioid addicts and the long-term cuts to Medicaid. “Legislation of this complexity almost always takes longer than anyone else would hope,” McConnell told reporters off the Senate floor as he pressed pause on legislation he would rather have kicked down on his to-do list in favor of other heavy lifts like tax reform or a big-ticket infrastructure package. “We’re still working toward getting at least 50 people in a comfortable place.”

That’s partly because voters are not sold on the idea. Clear majorities oppose the GOP plan in polls; one survey of the Senate proposal found that just 1 in 5 Americans supported the idea.

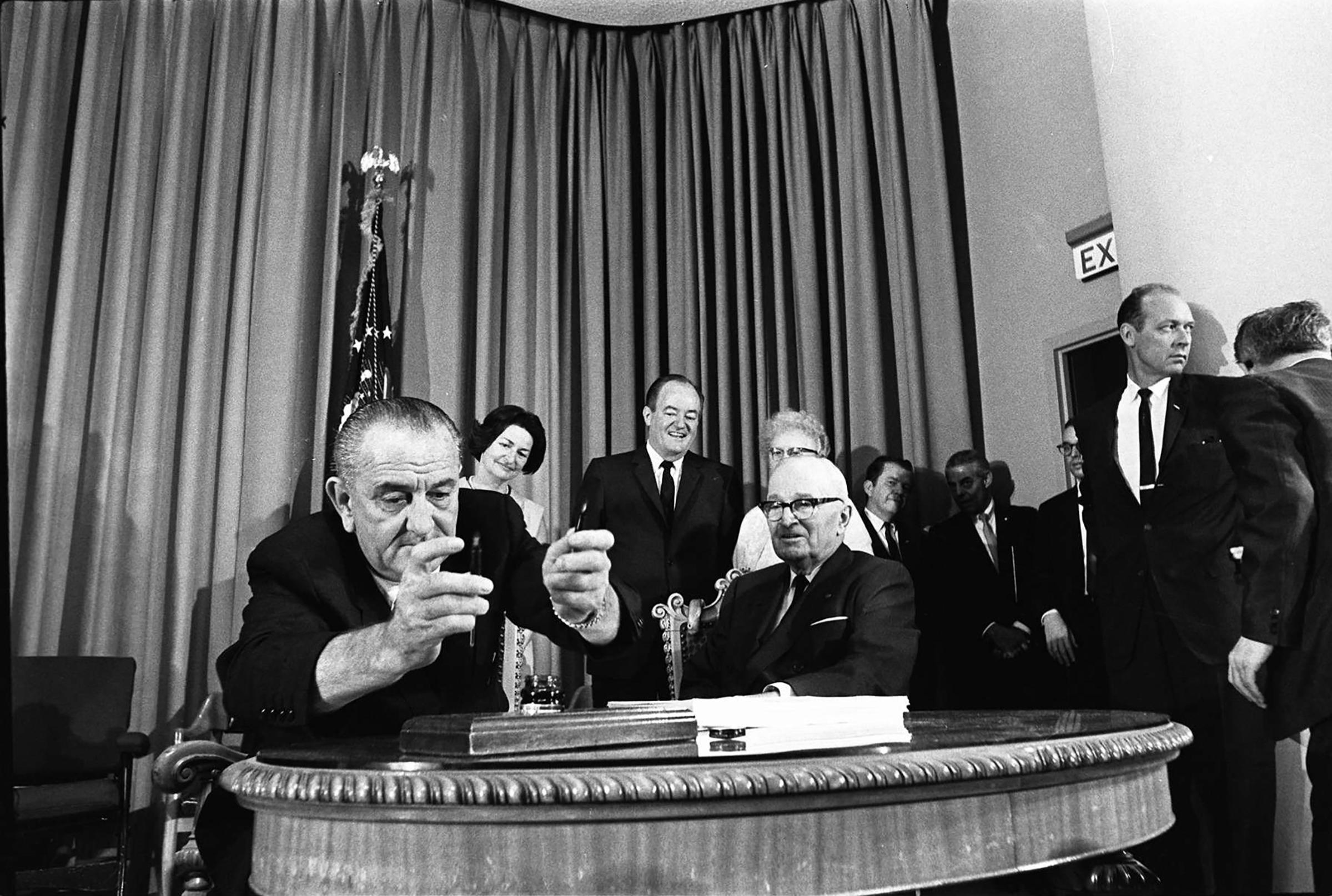

Medicaid traces its origins to 1965, when it was birthed as one of the pieces of Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society. Conservatives–who at the time were not exclusively Republicans–found the laws too ambitious and onerous for states, and too costly for federal taxpayers. In the intervening decades, conservative antipathy toward the program deepened as its costs rose, leading to higher taxes and larger deficits.

For a while, it sounded like President Trump would break with his party and emerge a Medicaid defender. “I’m not going to cut Medicare and Medicaid,” Trump promised in 2015, a vow he repeated in the months that followed. Since then he has sent mixed messages. After the House passed a measure dramatically scaling back Medicaid in May, he summoned allies and the press to a victory rally in the Rose Garden to praise lawmakers for taking action in the name of scrapping Obamacare. Later, he said the bill was “mean” and urged the Senate to come back with something “with heart.”

At the core of both the House and Senate bills is a reversal of the basic premise of Obamacare, which used new taxes on high-income workers and their investments to pay for more coverage and treatment for those in the lower-middle class. The Republican plans cut $701 billion in taxes over a decade on the wealthy while cutting health care for the poor and working poor. The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office says 22 million would lose their health coverage under the Senate bill, with 15 million being shed from Medicaid.

The measure starts to firm up the nation’s financial footing, but at the cost of its most vulnerable citizens. Seniors are among the most reliable voters, and threatening their final years’ care is seldom good politics.

The White House insists that the changes in spending shouldn’t be called a cut, since they are merely decreases from what everyone thought they’d spend in the coming years. “If you spent $100 last year on something, and we spend $100 on it this year–on that same thing–in Washington, people call that a cut,” White House Budget Director Mick Mulvaney said in May. As White House counselor Kellyanne Conway put it on June 25, “This slows the rate for the future.”

That leaves those steeped in the budget bemused, since no one expects health care to stop becoming more expensive. “If the federal government says, ‘Well, we’re only paying a certain amount going forward,’ then one of two things happen: either services are going to be cut or 25% of people who are currently covered are going to be cut,” says Andy Slavitt, a former administrator for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. “There’s no way around it–there’s not that much slack in state budgets.”

Here’s the rub: the states that have benefited the most from federal subsidies for state-run health care programs like Medicaid are often Republican. The non-college-educated, lower-income residents who helped fuel Trump’s rise to the White House often rely disproportionately on government-subsidized health care. Republican governors in several states, including Ohio, Arizona and Nevada, are panicked about the current plans, which reduce the number of insured and delay hard choices about which poor residents will be denied coverage starting next year. “They think that’s great? That’s good public policy?” an incredulous Ohio Governor John Kasich asked during a June 27 news conference in Washington. He had traveled to the capital to rally against his own party’s bid to overhaul one-sixth of the American economy. “Are you kidding me?”

Study after study shows the risks of skimping on relatively cheap procedures and the high return on investment for them, but that’s on the table too. Medical associations, whose members stand to lose patients, predict that higher long-term costs will result. “If women are not going to get mammograms and not going to get Pap smears, we’ll see an increase in breast cancer, in cervical cancer and in vulvar cancer,” says Dr. Hal Lawrence, executive vice president and CEO of the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. “There will be a cascade turning back the health of the nation.”

In fact, almost every major health care group, including the American Medical Association and hospital associations, oppose the Republicans’ proposals. “Most states are in a budget crisis, and if there is a federal reduction in Medicaid, then most states will not be able to make up the difference with state dollars,” says Kirsten Sloan, vice president for policy at the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network. “So we will mostly see states cut back. Cancer care is very expensive, and our fear is that one of the ways states will cut back is by cutting the most expensive care.”

When the Senate version landed on the desk of New Hampshire’s Republican Governor Chris Sununu, he initially wasn’t sure what to make of it. Fellow Republicans were gutting Medicaid programs in his state while offering up a relative pittance to fight opioids. Sununu asked his aides if there were loopholes or carve-outs that he was missing, if there were a way he could back the broader goal of repealing Obamacare. No, they told him. If the bill passes, it will result in $1.4 billion less in federal funding for his state in the next decade. About 186,000 residents receive some form of Medicaid in New Hampshire, and through the Medicaid expansion, more than 23,000 have received substance-abuse services. Medicaid provides $29 million to cover the costs of resources for school nurses and students with disabilities, along with 27% of births. As it does elsewhere in the nation, it also covers two-thirds of seniors in New Hampshire nursing homes. Sununu, a conservative Republican, decided to come out against the Senate Republican’s plan. “We simply do not see the resources necessary for us to craft a successful system that meets the needs of Granite Staters,” Sununu wrote to the Senate on June 27.

The next day, Sununu told TIME he felt boxed in. The proposals coming from Washington, where his father served as a White House chief of staff to George H.W. Bush and a brother was a Senator, are forcing governors to make impossible choices, he explained. “There’s only one way to account for that. You’re increasing taxes or cutting services or cutting constituents. All of those are really bad. We’re not talking just minor cuts. These are very serious and very deep cuts,” he said. Fellow Republicans, he said, had strayed from their electoral mandate: “The country is looking for reform on Obamacare. That’s where the sole focus needs to be. This goes beyond that.”

Back in the Senate, McConnell has talked about creating carve-outs to address some individual Senators’ concerns, including a pot of money to specifically target the opioid epidemic. Conservative activists, in turn, have attacked the Republican governors for betraying their ideological roots. And suspicion of widespread abuse, or opportunism, in the current Medicaid system is not limited to Washington. Susan Lees of Danbury, Conn., is a 50-year-old nanny and dog walker who is covered by Medicaid, which she pays some money toward. “A lot of them do need to go out and get a job. I’m not going to lie,” she says. “There are people out there who are soaking the system. I see it.”

Lees would be hard-pressed to convince the likes of Democratic Senator Maggie Hassan from New Hampshire, who met with TIME on a recent morning between meetings in her third-floor Senate office. As the phones rang incessantly with constituents calling in to voice their concerns about the bill, Hassan leaned back in her chair. For her, the Medicaid issue is personal. Her 28-year-old son Ben has severe cerebral palsy, cannot walk and gets most of his nutrition through a feeding tube. Like roughly 9 million other disabled people, he and his family benefit from Medicaid support.

“There’s a whole bunch of stuff that even the best private insurance doesn’t cover,” Hassan tells TIME. “Medicaid recognizes that there are some vagaries in life that hit some people harder than others. We never know when one of our children is going to be born with a particular condition that requires this kind of intensive care, not only to keep them alive but to keep them out of the hospital, out of intensive nursing homes, and be members of the community.”

If McConnell can find 50 Republican votes for the plan–and it is a big if, given Democrats’ unified resistance to this version of reform–the immediate effects will hit the District of Columbia and the 31 states that opted to expand Medicaid programs under Obamacare. In the next few years, they would face the task of deciding whether to cut health care spending or tell constituents like Josey Redder that services are no longer available. The 22-year-old Ridgefield, Conn., woman works as a waitress, earning $6 an hour, plus tips. “We work the jobs that we’re able to get, and those jobs don’t pay enough,” she said. So she turns to Connecticut’s Medicaid system for her doctor visits, birth control and therapy.

If leaders want to fill in the missing pieces, there are two answers: cut programs like schools or roads, or raise taxes. Almost every state is required to balance its budget, and they simply don’t have rainy-day funds large enough to cover an $834 billion shortfall from federal cuts over the next 10 years.

Health care spending thus could force lawmakers to ditch highway-exit ramps, welcome centers or college dormitories. Or, the state could direct patients to less-expensive (and often less-effective) treatments. The urgent would overtake the preventive, and mental health advocates worry that visible ailments would take priority over less obvious ones. “Mental illness, behavioral issues and addictions are chronic conditions,” says Arthur Evans, CEO of the American Psychological Association and one of the many critics of this plan. “They require sustained support over a period of time–sometimes years. When you truncate that and only give people help during crises, that sets them up for failure. It’s just expensive, and you don’t get the outcomes you want.”

Consider Hurteau. Her husband died from an overdose on June 11, 2015. She was in and out of jail for 10 years before his death, entering for the last time on Dec. 27 of that year. She had lost custody of her son and was addicted to heroin, and had no plan to remedy either situation. New Hampshire officials helped her enroll in a Medicaid program that provided counseling and treatment. Today she works to help others fight their addictions. “There’s a lot of potential behind the [prison] wall,” she says. “There’s a lot of opportunities for people with insurance, but without insurance, there’s no treatment.” For millions of Americans, that’s a prospect that should worry them.

–With reporting by ALICE PARK and HALEY SWEETLAND EDWARDS/NEW YORK; ZEKE J. MILLER, ALEX ALTMAN, JACK BREWSTER and ANNA RUMER/WASHINGTON

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Philip Elliott at philip.elliott@time.com